Published online Apr 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i15.4744

Peer-review started: September 3, 2014

First decision: September 27, 2014

Revised: October 11, 2014

Accepted: December 1, 2014

Article in press: December 1, 2014

Published online: April 21, 2015

Processing time: 229 Days and 22 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy and safety of integrin antagonists, including natalizumab and vedolizumab, in Crohn’s disease (CD).

METHODS: We carried out a literature search in PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library to screen for citations from January 1990 to August 2014. Data analysis was performed using Review Manager version 5.2.

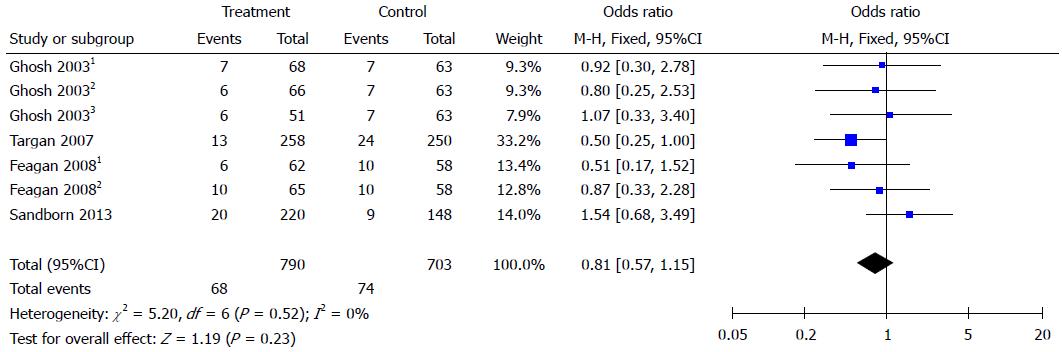

RESULTS: A total of 1340 patients from five studies were involved in this meta-analysis. During 6-12 wk treatment, integrin antagonists increased the rate of clinical response and remission with OR = 1.69, 95%CI: 1.37-2.09 and 1.84, 95%CI: 1.44-2.34, respectively. No significant difference was found between integrin antagonists and placebo treatments regarding their adverse reactions (OR = 1.07, 95%CI: 0.83-1.38) and serious adverse reactions (OR = 0.81, 95%CI: 0.57-1.15).

CONCLUSION: The results prove the efficacy and safety of integrin antagonists for CD treatment, although the treatment strategies varied.

Core tip: Integrin antagonists were used to treat Crohn’s disease (CD), but their efficacy and safety are not yet certain. We performed this systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy and safety of integrin antagonists, including natalizumab and vedolizumab, in CD. During 6-12 wk treatment, integrin antagonists increased the rate of clinical response and remission. There was no significant difference between integrin antagonists and placebo regarding their adverse reactions and serious adverse reactions. These results prove the efficacy and safety of integrin antagonists for CD treatment.

- Citation: Ge WS, Fan JG. Integrin antagonists are effective and safe for Crohn’s disease: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(15): 4744-4749

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i15/4744.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i15.4744

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a relapsing systemic inflammatory disease that commonly affects the gastrointestinal tract, with extraintestinal manifestations and associated immune disorders[1]. CD often leads to abdominal pain, fever, malaise, fatigue, diarrhea, fistula formation, bowel obstruction, and malnutrition. The common therapies for CD are aminosalicylates, steroids, immunosuppressants and monoclonal antibodies[2]. Aminosalicylates such as mesalamine and sulfasalazine are used to treat mild to moderate CD[3], while corticosteroids are used to treat acute active CD and patients who do not response to aminosalicylates[4]. However, the use of corticosteroids has a high risk of Cushing’s syndrome, infection and diabetes in the short term, and bone loss, increased ocular pressure and diabetes in the long term[5]. Immunosuppressants are used to inhibit inflammation. Long-term use of immunosuppressants may cause infection, liver toxicity and bone marrow suppression[6]. Biologic agents used to treat CD mainly consist of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibitors and α-integrin antagonists.

Natalizumab and vedolizumab are the integrin antagonists approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Natalizumab is a monoclonal antibody antagonizing α4β1 and α4β7 intergrin-mediated interactions in the gut and brain[7]. It is effective in treating CD but is limited by increasing the risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML)[8]. Vedolizumab is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody for α4β7 integrin. It only regulates gut lymphocyte trafficking, therefore, it is not likely to cause PML[9].

Previous studies have indicated the efficacy of integrin inhibitors in CD therapy. However, the sample size of those studies was small. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis including current double-blind randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to evaluate the efficacy of integrin antagonists for CD treatment.

EMBASE, MMEDLINE, PubMed and Cochrane Library were searched for RCTs from January 1990 to August 2014. The key words “Crohn disease” and “natalizumab” or “MLN0002” or “vedolizumab” were used in screening relevant citations. The inclusion criteria were: (1) RCTs; and (2) studies provided data for at least one of the main outcomes, including rate of clinical response, rate of clinical remission, common adverse reactions, and serious adverse reactions. Clinical remission was defined as Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score < 150 and clinical response was defined as a decrement of ≥ 70 points in CDAI score from baseline (week 0).

The following information was extracted from each study: first author name; year of publication; number of patients; rate of clinical response; rate of clinical remission; number of common adverse reactions; and number of serious adverse reactions. The Jadad score was used to assess the quality of included studies. Studies with score ≥ 3 were regarded as high-quality RCTs, while studies with score < 3 were defined as low-quality RCTs.

Data analysis was performed using RevMan version 5.2 for each individual study, and dichotomous data were reported as OR with 95%CI. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed by Cochrane Q statistics and I2 test. A significant level of ≥ 50% for I2 test was considered as evidence of heterogeneity. A fixed-effect model was used when there was no evidence of heterogeneity, otherwise a random-effect model was chosen. Ghosh et al[10] used three different treatment strategies and Feagan et al[11] used two. Each treatment strategy was regarded as a single treatment group. All of the treatments were analyzed together.

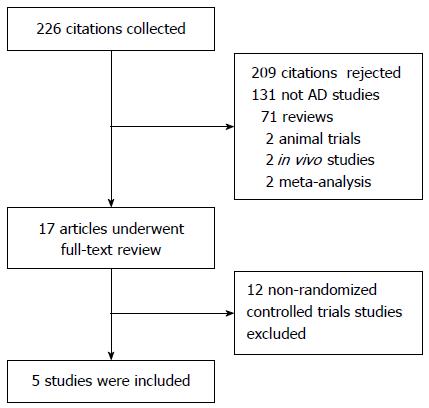

A total of 226 citations were obtained via database searches, and five met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). A total of 1340 patients were involved; 462 were treated with natalizumab, 347 with vedolizumab, and 531 with placebo. The information in these citations is summarized in Table 1. All five studies had a Jadad score ≥ 3 (Table 1).

| Ref. | Study duration | Treatment | Age(mean, yr) | Disease duration (yr) | Baseline CDAI(mean) | Jadad score |

| Gordon et al[12], 2001 | 12 | Natalizumab 3 mg/kg intravenous infusion at 0 wk, n = 18 | 36 | 8.5 | 258 | 5 |

| Placebo intravenous infusion at 0 wk, n = 12 | 34 | 8.4 | 273 | |||

| Ghosh et al[10], 2003 | 12 | Natalizumab 6 mg/kg intravenous infusion at 0, 4 wk, n = 51 | 35 | 7.8 | 298 | 5 |

| Natalizumab 3 mg/kg intravenous infusion at 0, 4 wk, n = 66 | 36 | 8.1 | 300 | |||

| Natalizumab 3 mg/kg intravenous infusion at 0 wk, n = 68 | 36 | 8.4 | 288 | |||

| Placebo intravenous infusion at 0, 4 wk, n = 63 | 34 | 8.9 | 300 | |||

| Targan et al[13], 2007 | 12 | Natalizumab 300 mg intravenous infusion at 0, 4, 8 wk, n = 259 | 38 | 10.1 | 304 | 5 |

| Placebo intravenous infusion at 0, 4, 8 wk, n = 250 | 38 | 10 | 300 | |||

| Feagan et al[11], 2008 | 8 | Vedolizumab 2 mg/kg intravenous infusion at 0, 4 wk, n = 65 | 39 | 8 | 297 | 5 |

| Vedolizumab 0.5 mg/kg intravenous infusion at 0, 4 wk, n = 62 | 36 | 8.8 | 288 | |||

| Placebo intravenous infusion at 0, 4 wk, n = 58 | 35 | 9 | 288 | |||

| Sandborn et al[14], 2013 | 6 | Vedolizumab 300 mg intravenous infusion at 0, 2 wk, n = 220 | 36 | 9.2 | 327 | 5 |

| Placebo intravenous infusion at 0, 2 wk, n = 148 | 39 | 8.2 | 325 |

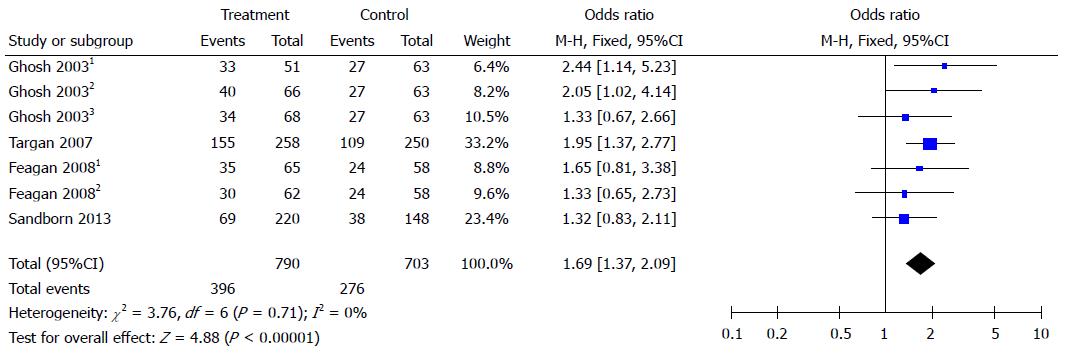

Clinical response was reported in four studies. According to the results of the meta-analysis, integrin antagonists increased the clinical response to CD. The OR for clinical response was 1.69 (95%CI: 1.37-2.09). There was no heterogeneity as I2 = 0% (Figure 2).

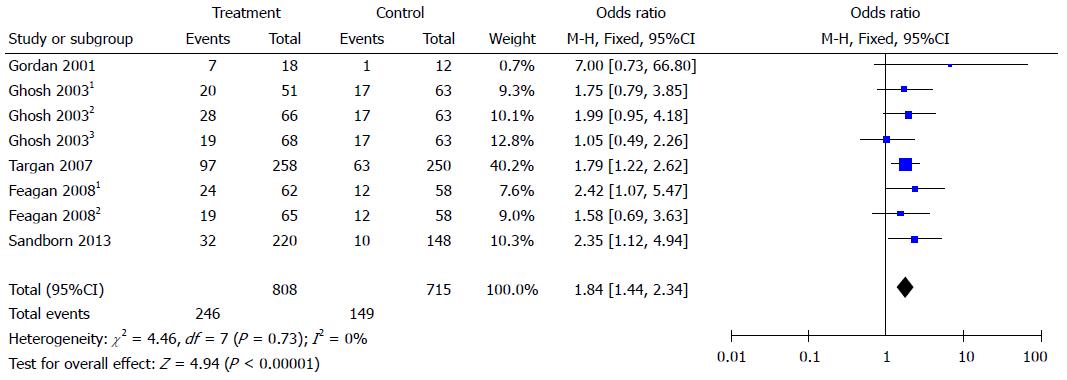

Clinical remission was reported in five studies. Integrin antagonists had a higher rate of remission than placebo. The OR for clinical remission was 1.84 (95%CI: 1.44-2.34). There was no heterogeneity as I2 = 0% (Figure 3).

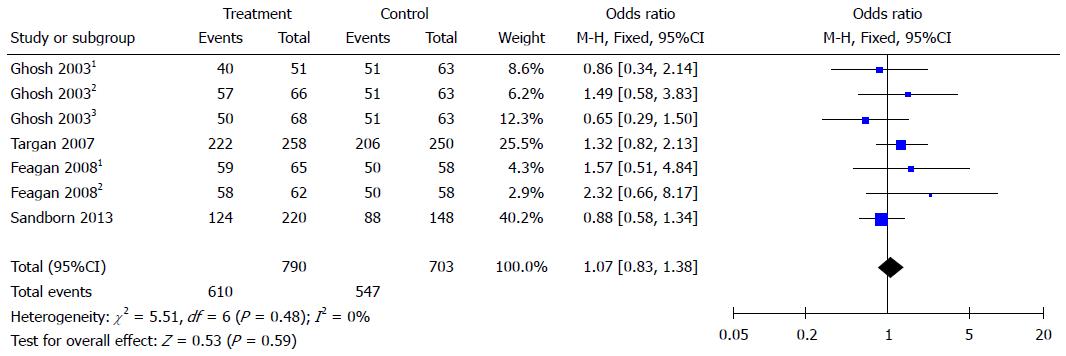

Natalizumab and vedolizumab were both well tolerated during treatment. They had similar rates of common adverse reactions (OR = 1.07, 95%CI: 0.83-1.38) and serious adverse reactions (OR = 0.81, 95%CI: 0.57-1.15) compared to placebo (Figures 4 and 5).

The incidence of CD is increasing worldwide, with more young patients, and it requires life-long medical and surgical input[15]. Over the past few decades, TNF-α inhibitors such as infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, and golimumab have been used in patients with moderate to severe CD who failed to respond to corticosteroids[16]. TNF-α inhibitors have been proved effective in CD treatment, however 40% of patients will lose their response to them at a rate of 10%-13% per year[17]. This led to the search for an alternative way to treat CD. It was found that the migration of leukocytes and other inflammatory cells into the intestinal vasculature and disruption of intestinal barrier function were important in the pathogenesis of CD[18]. The integrin antagonists (natalizumab and vedolizumab) aim to block the interaction between leukocytes and endothelial cells to inhibit inflammation[19]. One RCT showed that vedolizumab can lead to clinical remission at 10 wk in patients who failed TNF antagonist treatment[20].

Our meta-analysis suggested that short-term treatment with integrin antagonists could improve the clinical response and remission in CD patients. Compared to placebo, patients treated with 6 mg/kg natalizumab at 0 and 4 wk showed the highest OR for clinical response (OR = 2.44, 95%CI: 1.14-5.23), followed by 3 mg/kg natalizumab at 0 and 4 wk (OR = 2.05, 95%CI: 1.02-4.14). However, there was no significant difference between natalizumab and vedolizumab in terms of clinical response and remission.

According to meta-analysis results, integrin antagonists had a similar rate of adverse reactions as the placebo group. Previous studies showed that natalizumab could increase the risk of PML at a rate of 0.09-11 per 1000 patients[8]. Vedolizumab was designed to target the α4β7 integrin heterodimer and cannot cross the blood-brain barrier[21]. There are no reported cases of PML in patients treated with vedolizumab for CD[22]. However, we did not find PML reported in the included studies and compared to placebo, both natalizumab and vedolizumab had a similar rate of serious adverse reactions.

There were some limitations to our study. The treatment strategies were different for each study. For example Ghosh et al[10] used 3 mg/kg natalizumab, while Targan et al[13] used a fix dose of 300 mg. The duration of treatment also varied. The inclusion criteria differed among the trials. Sandborn et al[14] included patients who previously received TNF antagonist therapy; however, these patients were excluded from the other four trials. Despite these limitations, we believe that our analysis could contribute to the comprehensive evaluation of integrin antagonists in CD.

Our meta-analysis suggested that integrin antagonists were effective in improving CD response and remission rates with a similar rate of adverse reactions compared to placebo. However, due to the small size of samples in our study, large multicenter RCTs are needed to confirm our findings.

Crohn’s disease (CD) can affect the gastrointestinal tract, with extraintestinal manifestations, and often leads to abdominal pain, fever, malaise, fatigue, diarrhea and bowel obstruction. Traditional therapies for CD are aminosalicylates, steroids, immunosuppressants and monoclonal antibodies. However, they all have an apparent adverse effects. Integrin antagonists including natalizumab and vedolizumab aim to block the interaction between leukocytes and endothelial cells. Previous studies have reported that integrin antagonists can inhibit inflammation.

Natalizumab is a monoclonal antibody antagonizing α4β1 and α4β7 integrin-mediated interactions in the gut and brain, while vedolizumab is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody for α4β7 integrin. Current studies have reported that integrin antagonists can relieve symptoms in CD.

Previous studies have reported that natalizumab and vedolizumab are effective in CD treatment. However, these trials were small and there is still a lack of large multicenter trials. To evaluate the efficacy and safety of integrin antagonists, including natalizumab and vedolizumab, the authors performed a meta-analysis that overcame the limitation of small trials. To date, no meta-analysis has been published for CD that has evaluated the efficacy and safety of integrin antagonists. Thus, the aim of this study was to carry out a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of published RCTs in order to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the integrin antagonists, and this may contribute important results to the evidence-based health care evaluation of CD that might support clinical as well as financial decision making.

This study suggests that integrin antagonists are effective in improving CD response and remission rate although the treatment strategies are varied. Compared with placebo, integrin antagonists have a similar safety profile.

CD is a relapsing systemic inflammatory disease that commonly affects the gastrointestinal tract with extraintestinal manifestations and associated immune disorders. CD often leads to abdominal pain, fever, malaise, fatigue, diarrhea, fistula formation, bowel obstruction, and malnutrition. Integrin antagonists are antibodies that aim to block the interaction between leukocytes and endothelial cells to inhibit inflammation including natalizumab and vedolizumab.

This study shows a meta-analysis that reviews the clinical evidence about the use of Integrin antagonists as a new treatment in refractory CD. Five papers meet with rigorous inclusion criteria and their analysis reported interesting data.

P- Reviewer: Garcia-Olmo D S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Kerr C E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2012;380:1590-1605. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1347] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1443] [Article Influence: 120.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dudley-Brown S, Nag A, Cullinan C, Ayers M, Hass S, Panjabi S. Health-related quality-of-life evaluation of crohn disease patients after receiving natalizumab therapy. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2009;32:327-339. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nielsen OH, Munck LK. Drug insight: aminosalicylates for the treatment of IBD. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:160-170. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 96] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | De Cassan C, Fiorino G, Danese S. Second-generation corticosteroids for the treatment of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: more effective and less side effects? Dig Dis. 2012;30:368-375. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, Salzberg BA, Diamond RH, Chen DM, Pritchard ML, Sandborn WJ. Serious infections and mortality in association with therapies for Crohn’s disease: TREAT registry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:621-630. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 654] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 624] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kandiel A, Fraser AG, Korelitz BI, Brensinger C, Lewis JD. Increased risk of lymphoma among inflammatory bowel disease patients treated with azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine. Gut. 2005;54:1121-1125. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 583] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 572] [Article Influence: 30.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sandborn WJ, Yednock TA. Novel approaches to treating inflammatory bowel disease: targeting alpha-4 integrin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2372-2382. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 73] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bloomgren G, Richman S, Hotermans C, Subramanyam M, Goelz S, Natarajan A, Lee S, Plavina T, Scanlon JV, Sandrock A. Risk of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1870-1880. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 915] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 887] [Article Influence: 73.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Soler D, Chapman T, Yang LL, Wyant T, Egan R, Fedyk ER. The binding specificity and selective antagonism of vedolizumab, an anti-alpha4beta7 integrin therapeutic antibody in development for inflammatory bowel diseases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;330:864-875. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 325] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ghosh S, Goldin E, Gordon FH, Malchow HA, Rask-Madsen J, Rutgeerts P, Vyhnálek P, Zádorová Z, Palmer T, Donoghue S. Natalizumab for active Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:24-32. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 648] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 612] [Article Influence: 29.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Feagan BG, Greenberg GR, Wild G, Fedorak RN, Paré P, McDonald JW, Cohen A, Bitton A, Baker J, Dubé R. Treatment of active Crohn’s disease with MLN0002, a humanized antibody to the alpha4beta7 integrin. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1370-1377. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 225] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gordon FH, Lai CW, Hamilton MI, Allison MC, Srivastava ED, Fouweather MG, Donoghue S, Greenlees C, Subhani J, Amlot PL. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of a humanized monoclonal antibody to alpha4 integrin in active Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:268-274. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Targan SR, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Lashner BA, Panaccione R, Present DH, Spehlmann ME, Rutgeerts PJ, Tulassay Z, Volfova M. Natalizumab for the treatment of active Crohn’s disease: results of the ENCORE Trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1672-1683. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 446] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Hanauer S, Colombel JF, Sands BE, Lukas M, Fedorak RN, Lee S, Bressler B. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:711-721. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1416] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1486] [Article Influence: 135.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Barkema HW. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46-54.e42; quiz e30. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3134] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3398] [Article Influence: 283.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 16. | Singh S, Pardi DS. Update on anti-tumor necrosis factor agents in Crohn disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:457-478. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y. Review article: loss of response to anti-TNF treatments in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:987-995. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 393] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 439] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cominelli F. Inhibition of leukocyte trafficking in inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:775-776. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P. Physiological basis for novel drug therapies used to treat the inflammatory bowel diseases. I. Immunology and therapeutic potential of antiadhesion molecule therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G169-G174. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sands BE, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Sy R, D’Haens G, Ben-Horin S, Xu J, Rosario M. Effects of vedolizumab induction therapy for patients with Crohn’s disease in whom tumor necrosis factor antagonist treatment failed. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:618-627.e3. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 462] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 509] [Article Influence: 50.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Milch C, Wyant T, Xu J, Parikh A, Kent W, Fox I, Berger J. Vedolizumab, a monoclonal antibody to the gut homing α4β7 integrin, does not affect cerebrospinal fluid T-lymphocyte immunophenotype. J Neuroimmunol. 2013;264:123-126. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gilroy L, Allen PB. Is there a role for vedolizumab in the treatment of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease? Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2014;7:163-172. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |