Published online Jun 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i22.6744

Revised: December 19, 2013

Accepted: March 5, 2014

Published online: June 14, 2014

Processing time: 231 Days and 11.8 Hours

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is considered a biopsychosocial disorder, whose onset and precipitation are a consequence of interaction among multiple factors which include motility disturbances, abnormalities of gastrointestinal sensation, gut inflammation and infection, altered processing of afferent sensory information, psychological distress, and affective disturbances. Several models have been proposed in order to describe and explain IBS, each of them focusing on specific aspects or mechanisms of the disorder. This review attempts to present and discuss different determinants of IBS and its symptoms, from a cognitive behavioral therapy framework, distinguishing between the developmental predispositions and precipitants of the disorder, and its perpetuating cognitive, behavioral, affective and physiological factors. The main focus in understanding IBS will be placed on the numerous psychosocial factors, such as personality traits, early experiences, affective disturbances, altered attention and cognitions, avoidance behavior, stress, coping and social support. In conclusion, a symptom perpetuation model is proposed.

Core tip: Irritable bowel syndrome is a complex, biopsychosocial disorder usually developing under stress, which builds upon hypersensitization, underlined by physiological specificities and heightened neuroticism. Symptom onset is followed by inappropriate cognitive interpretations that can be accompanied by affective disturbances. We consider increased attention to visceral sensation and different manifestations of anxiety to be key components that may lead to symptom exacerbation and perpetuation. This applies to patients who express higher trait neuroticism and are more prone to interpret even mild somatic changes as serious symptoms. An individualized approach is necessary for each patient to estimate current physical and psychological status.

- Citation: Hauser G, Pletikosic S, Tkalcic M. Cognitive behavioral approach to understanding irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(22): 6744-6758

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i22/6744.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i22.6744

One of the most common functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) is irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), broadly defined as a variable combination of chronic gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, such as abdominal pain and discomfort and change in stool form and frequency, that are not explained by structural or biochemical abnormalities[1]. Additional characteristics include a high female predominance, heterogeneity of symptoms in relation to the predominating bowel habit (constipation-predominant, diarrhea-predominant or alternating symptoms) and common extraintestinal symptoms and comorbidity[2].

Despite a large body of research, IBS is still poorly understood and there is a need for a more comprehensive model of the disorder. It is currently accepted that symptom formation involves an interaction among multiple factors that include motility disturbances, abnormalities of GI sensation, GI inflammation and infection, altered processing of afferent sensory information, psychological distress and affective disturbances[1,3,4]. In other words, IBS is considered a biopsychosocial disorder[5].

This review addresses the biological and psychosocial factors that possibly contribute to the onset and perpetuation of IBS symptoms. In the first part of the review we describe previous findings on different components of the cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) model that are relevant for understanding IBS. In the second part of the review we present a new model of IBS symptom perpetuation in which attention to visceral sensation and different manifestations of anxiety have a central role.

According to the biopsychosocial model[6] illness is viewed as a multifactorial entity resulting from the interactions between psychosocial and biological factors in the etiology and progression of the disease[7]. This model has become popular in explaining and clarifying the etiological mechanisms relevant for functional somatic syndromes in general and functional GI disorders in particular[8-11]. Several specific biopsychosocial models of IBS have been proposed, some emphasizing the contribution of biobehavioral factors[4,12-14] and others emphasizing the contribution of psychosocial factors[15-18].

There is a consensus that a CBT approach offers a generic framework for understanding functional somatic syndromes, such as IBS, while also providing effective treatment[5,11,19-24]. This approach is based on the classical CBT model of emotional distress proposed by Beck[25], which distinguishes between its developmental predispositions and precipitants, and its perpetuating cognitive, behavioral, affective and physiological factors. The CBT model has several advantages, for example, it uses operationally defined concepts resulting in a large body of supporting research and it is implemented in a wide range of illnesses, from heart disease to IBS[11,25].

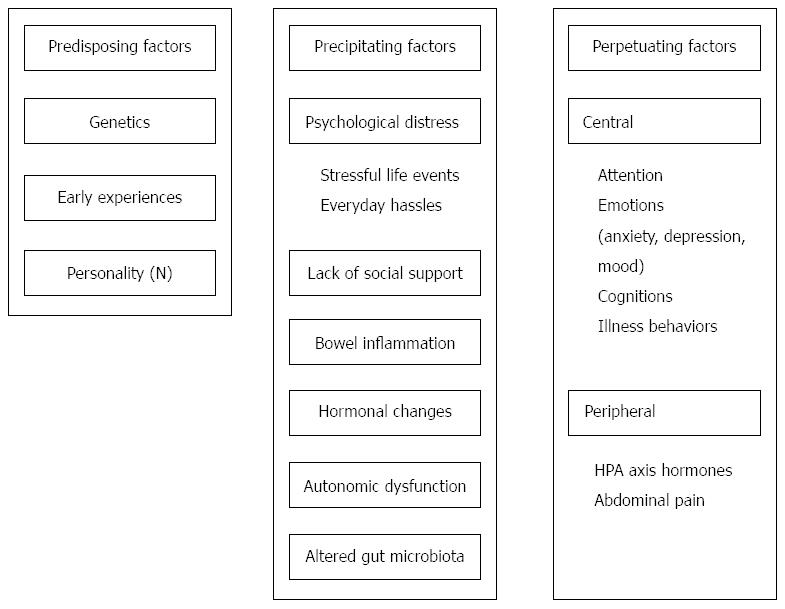

The CBT model is built around three core concepts that help define the development and maintenance of IBS symptoms[11,20,21]. The first of these concepts incorporates the biopsychosocial assumption that biological (e.g., bowel inflammation, hormonal changes, autonomic dysfunction, and abdominal pain), psychological (e.g., altered attention, anxiety and depression, symptom interpretations, and illness behavior) and social (e.g., environmental influences and social support) domains are equally important components in the understanding of illness. The second core concept is the differentiation among predisposing vulnerabilities for IBS (e.g., genetics, early experiences, and neuroticism), those that precipitate the development of this condition (e.g., adverse life events and everyday hassles), and those that maintain them once they have been established (e.g., sensitization and selective attention). Finally, the third core concept of the model is the assumption that individuals can take control of the effect their illness has on their life by changing their cognition and behavior, which affects physiology and emotion, and vice versa.

In Figure 1 we illustrate the core concepts of the CBT model of IBS. This model is based on the existing data on IBS patients and it incorporates various aspects of the disorder, which have already been recognized as important by other researchers in previously published models[4,12-18].

Although the model separates predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating factors, one must keep in mind that they are continuously involved in bidirectional interactions, which means that in the context of mechanisms and processes they cannot be separated. Some components of the model can be considered either as predisposing, precipitating or perpetuating, depending on context, personal history or current illness status. For example, trait anxiety is related to neuroticism as a possible predisposing factor, state anxiety is a common reaction to various stressful situations (precipitating factor), but anxiety sensitivity also plays an important role in perpetuating the symptoms of the disorder.

Each of the model components will be described in detail in the context of IBS.

This component of the model relates to those factors that increase an individual’s susceptibility to developing a wide range of functional disorders. Among them, genetics may play an important role but due to lack of obvious pathology (e.g., specific biomarkers of disease) research for specific genes has been difficult. Genetic predispositions are shaped by early experiences that have been found to have significant influences on illness development. Finally, neuroticism as a personality trait has been repeatedly confirmed as a general predisposition for experiencing distress and has been recognized as a common trait underlying vulnerability to various illnesses[20,26,27].

In spite of some inconsistent findings there is a general accordance with the hypothesis that IBS may be a complex genetic disorder. Family and twin studies have clearly established a genetic component in IBS and several studies point to genetic contributions to IBS[28,29]. Gut motility, visceral secretion, persistent pain, mood, sensation and inflammation are greatly influenced by genotype. There are several potential candidate genes that are associated with IBS. Research has focused on the relations of various gene polymorphisms with IBS symptom manifestations. Gene polymorphisms involve the serotonergic, adrenergic and opioidergic systems, and genes encoding proteins with immunomodulatory and/or neuromodulatory features[30]. A detailed review of genetic polymorphisms is beyond the scope of this paper, therefore, only a few are mentioned (for a full review, see Fukudo and Kanazawa[31]). One of the well-studied potential genetic groups involves the genes related to serotonergic mechanisms. Serotonin transporter or solute carrier 6A4 (SLC6A4) is the protein involved in serotonin reuptake after it has interacted with the downstream receptor. SLC6A4 is also expressed in the GI tract and there are conflicting data as to whether it is underexpressed in mucosal biopsies of IBS patients[32,33]. This may be partly because of small sample sizes and ethnic heterogeneity within the cohorts studied. Mutations in the serotonin receptor gene (5-HT2A, 5-HT3A and 5-HT3D) are another important mechanism that can cause disturbed serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT) function. Higher expression can be associated with more severe pain in patients with IBS[34]. Furthermore, serotonin transporter polymorphism (5-HTT) can predispose towards stress hypersensitivity in patients with IBS[35]. Of course, a cautious approach is needed before making firm conclusions about the genetics of IBS. Some of the studies in this field have certain methodological issues, or are yet to be replicated.

Research indicates there is a relatively high (30%-56%) rate of abuse history among IBS patients[36], even when compared to patients with organic GI diseases[37]. A population-based survey has revealed that the prevalence of childhood abuse is significantly higher in persons with IBS compared to those without IBS[38]. In addition, there is a higher likelihood of GI symptoms in victims of abuse[39], which implies that there is a relationship between abuse and GI symptoms. Research on early adverse life events, which encompass a wider array of traumatic experiences than abuse alone, shows similar results. In a study by Chang[40], IBS was associated with a higher total early life trauma score, which included general trauma, as well as physical, emotional and sexual abuse under the age of 18 years. This relationship was significant even after controlling for anxiety and depression. In another study[41], female IBS patients reported a higher prevalence of general trauma, physical punishment, emotional abuse, and sexual events when compared to healthy controls. Emotional abuse was the strongest predictor of IBS. Although IBS treatment is primarily directed at precipitating factors while early experiences are a possible predisposing factor, addressing them during treatment might be beneficial for symptom reduction and quality of life improvement.

Research in several countries has shown that IBS patients have higher levels of trait neuroticism than healthy persons have[42-49]. Neuroticism refers to a broad dimension of individual differences in the tendency to experience negative emotions and express associated behavioral and cognitive traits. Some of the traits that define neuroticism are fearfulness, social anxiety, helplessness, poor inhibition of impulses and irritability[50]. Even though neuroticism scores vary slightly depending on age, sex and socioeconomic status, studies of the associations of neuroticism and health have controlled for these demographic factors and still found a significant negative association of neuroticism and health. Neuroticism has been linked to several mental disorders as well as physical health problems, even when depression is controlled for[26]. In IBS patients, high neuroticism has been linked to higher pain reports[46] and low response to treatment with antidepressants[51].

In addition to neuroticism, other fundamental personality traits included in the concept of the five factor personality model (“The Big Five”: neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, openness, and conscientiousness) have been used to describe behavioral patterns of IBS patients. The findings related to other personality traits, however, are much less consistent than those found for neuroticism. Some studies have shown that IBS patients have lower agreeableness[44,49] and openness scores than healthy subjects[43,44,49], while others report no differences in agreeableness[42,43,47] or openness[42,47]. Extraversion is also sometimes reported as lower in IBS patients, for example, compared to peptic ulcer patients[52] or healthy controls[42,48], and other times no differences are found between IBS patients and healthy controls[43,44,47]. Studies have also reported higher conscientiousness scores in IBS patients than in healthy subjects[43,44], although there are reports of no differences[47,49] and even opposite results[42]. Personality traits may be important for IBS symptom expression, especially neuroticism, which has been established as a critical trait underlying general disease vulnerability.

The second component of the CBT model of IBS refers to factors whose occurrence relatively closely precedes the onset of the illness, while the third component refers to factors that maintain and perpetuate the illness symptoms. As Deary et al[20] have appropriately illustrated, they present a unique autopoietic interaction of cognitive, behavioral and physiological factors for each individual. Both of these groups of factors are a result of specific psychological and physiological reactions that are determined by predisposing factors and could play a precipitating role in certain circumstances or a perpetuating role in others. For example, people with high levels of neuroticism are more likely to perceive minor physical symptoms or somatic changes as serious symptoms of possible disorder[23]. They are also more prone to interpreting events as negative, which could lead to higher levels of reported psychological distress, both in the context of major life events and everyday hassles, which may be related to specific avoidance behavior. Additionally, physiological factors such as mild bowel inflammation or alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis hormones, which may be a result of previous infection, or any combination of predisposing factors (genetics, early experience, or personality traits), also play roles in IBS symptom generation and maintenance.

Stressful life events and everyday hassles: Around three quarters of IBS patients report that stress causes them abdominal pain and bowel motility changes. In line with a history of early adverse experiences, IBS patients report a significantly higher number of stressful life events[53,54]. Research findings emphasize the importance of differentiating between a positive or negative assessment of a stressful event. Although patients with functional and organic GI diseases report similar numbers of stressful life events, patients with IBS and other functional diseases report more negative[51,55] and less positive stressful events[56]. It could be speculated that this is related to higher levels of neuroticism in the IBS population, making these patients more likely to interpret events in a negative manner. Research also shows a greater prevalence of IBS among male war veterans than the general population, which could be related to increased psychological stress, traumatic experiences and posttraumatic stress disorder[55]. Additionally, IBS prevalence is high (46%) among primary caregivers of chronically ill patients[57]. Taking all of these findings into consideration, there is strong evidence of a relationship between IBS and chronic or life stress.

Research on everyday hassles in IBS patients shows that daily levels of stress are related to symptom severity[58,59]. Even when neuroticism is controlled for, IBS patients report higher everyday stress levels than healthy subjects and subjects with digestion problems who do not meet the IBS criteria[59]. IBS patients perceive stressful events as more severe than inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients do, but considering that both patient groups have similar lowered levels of health related quality of life (HRQoL), it seems that both groups have similar levels of psychological stress[60].

Social support: Social support refers to any and all processes by which social relations can affect physical or psychological health[61,62]. Perceived social support is defined as a person’s perception that other people will provide them with support when needed. Many studies indicate that perceived social support is more important for the person’s health than objective indicators of received social support. It is believed that the cause of this finding could be the experience of acceptance and care of significant others[62]. From a cognitive perspective, social support acts by changing the cognitive appraisal of stressful situations. Perceived social support reduces the impact of stressful events on health either through supportive behavior of others or through the belief that support is available. It is presumed that supportive behavior improves coping, and that the perception of support availability leads to assessing the situation as less stressful[63].

Research shows that IBS patients report receiving significantly less interpersonal support than healthy persons do[64]. Higher support has been linked to lower symptom scores[65,66], but the question about the directionality of the relationship still remains. It is possible that support may lead to lower symptom scores, but it is also possible that patients with lower symptom scores elicit less anxiety and distress in significant others, making them more susceptible to provide help and support[65]. Additionally, it is possible that IBS patients with high symptom scores view their social support as less satisfactory due to their own psychological characteristics such as high neuroticism[42-49,66]. The effect of perceived social support on physical pain seems to be mediated by stress, more specifically - the higher the perceived social support, the lower the reported levels of stress and physical pain[66]. Findings also suggest that satisfaction with social support mediates the relationship between psychological distress and perceived stress. When perceived stress is low, satisfaction with social support does not affect the levels of psychological distress. However, when the levels of perceived stress are high, satisfaction with social support leads to the reduction of psychological distress[67].

Coping with stress is influenced by assessment of environmental and personal resources, hence social support can also be conceptualized as assistance with coping[62]. In line with the results of social support studies, research shows that IBS patients have lower coping capabilities than IBS non-patients, that is, persons without an IBS diagnosis who match IBS criteria but have not sought medical help[56]. When investigating the use of different coping strategies, research shows that IBS patients with a predominantly positive affect (low levels of anxiety, depression, negative mood and perceived stress) seek social support more often than IBD patients with a positive affect, IBS patients with negative affect and healthy controls[68]. Crane and Martin[69] found no differences between IBS and IBD patients in the use of passive coping strategies. Higher levels of anxiety and depression were associated with higher levels of behavioral passive coping in both groups, and with emotional passive coping in the IBS group alone. It seems that IBS patients use different coping mechanisms than healthy persons use, which could be a result of differences in personality characteristics. Research shows that in general, high extraversion and low neuroticism are predictors of high perceived social support[70]. IBS patients have higher levels of neuroticism[42-49], and perhaps lower levels of extraversion than healthy persons[42,48], thus, it is possible that their perceived social support is lower, which contributes to the negative impact of stress on their symptoms. Although research so far[66] has not established perceived social support as a predictor of HRQoL in IBS patients, further research is needed in this area.

Affective status: Research consistently shows that IBS patients present with higher levels of anxiety and depression than healthy persons[48,71-74]. Moreover, heightened levels of anxiety and depression were identified as predictors of IBS in a general population sample[75]. IBS non-patients also show higher anxiety levels than healthy persons show[45]. Pace et al[60] found that, although IBS and IBD patients have different levels of physical symptom severity, there are no differences in their psychological symptom severity, such as stress and anxiety. However, IBD patients with IBS-like symptoms report higher levels of anxiety and depression than IBD patients without IBS-like symptoms[76]. Furthermore, psychiatric comorbidity in the IBS population is common. A meta-analysis of 244 studies[77] showed that patients with FGIDs, including IBS patients, more frequently suffer from anxious and depressive disorders compared to healthy persons or patients with similar diseases of known organic pathology. IBS patients with comorbid psychiatric diagnoses report higher levels of anxiety, anxiety sensitivity, and worry[78].

Anxiety sensitivity is a stable personality trait distinguished from trait anxiety, which has also been found to be a risk marker for anxiety pathology. Unlike trait anxiety, which refers to the predisposition to respond anxiously to a wide range of stressors, anxiety sensitivity describes a more specific tendency to fearfully respond to one’s own anxiety symptoms[79]. It is characterized by hypersensitivity to somatic sensations based on the belief that they have harmful physical, psychological, or social consequences[79,80]. An important construct that encompasses contextual cues or stressors, in addition to the interoceptive ones, is GI-specific anxiety. GI-specific anxiety can be defined as GI-related cognition, affect and behavior, which stem from fear of GI sensations, symptoms, and the context in which these sensations and symptoms occur[81]. GI-specific anxiety may be an especially important variable related to increased pain sensitivity, hypervigilance, and poor coping responses[45,81]. It could be hypothesized that other measures of psychological distress (neuroticism, anxiety sensitivity, and state anxiety) relate to IBS symptom severity through GI-specific anxiety[80].

Attention and perception: One of the possible mechanisms in IBS could be enhanced perception of, and selective attention to visceral stimuli, resulting from the dysfunction of the digestive system[82-84]. Conversely, central mechanisms that enhance responses to interoceptive information may be critical for maintaining and exacerbating symptoms[85]. The disruption of central brain control mechanisms that modulate the motility and sensation of the gut might be even more important than bowel dysfunction itself[86]. Research shows that patients with functional bowel disorders express attention-dependent alterations of central nervous system processing, as well as a generally negative emotional tendency in their cognitive processing strategies[87]. Models of attention to emotional material can be applied to the issue of attention-dependent alterations in IBS. Mogg and Bradley’s[88] model of cognitive motivational analysis and Mathews and Mackintosh’s[89] model of a competitive activation network, point out that a valence or threat evaluation system enhances the activation of any items identified as potentially threatening thereby increasing automatic selective attention to such items. The first model[88] proposes two cognitive structures mediating attention-emotion interaction: (1) valence evaluation system (VES), which automatically evaluates threat posed by the stimulus; and (2) goal engagement system (GES), which controls current processing according to goals set by the individual. When VES is activated by the presence of a threatening stimulus it sends a signal to the GES, which interrupts current processing and orients attentional resources to the material signaled by the VES. Similarly, Mathews and Mackintosh’s[89] model proposes that the threat-evaluation system enhances the representation of threatening stimuli in the competition for attentional resources. These models point to individual differences in attentional biases toward threatening stimuli[20,90].

Afzal et al[82] found evidence for selective processing of GI-symptom-related words compared with neutral words in IBS patients. A study by Kilpatrick et al[85] used the acoustic startle response to examine the early preattentive stages of information processing, and found that male IBS patients have a decreased ability to filter information, while female IBS patients have increased vigilance and greater attention to threat. Similarly, Martin and Chapman[91,92] used a modified exogenous cueing task on IBS patients and found signs of increased vigilance to GI symptoms. The authors showed that IBS patients have a faster orientation response to social threat and pain words than to neutral stimuli. In our recent study[93] we found evidence for Stroop facilitation to situational threat words. The facilitation index was positively associated with trait anxiety and GI-specific anxiety. Increased anxiety and worries about visceral symptoms led to a faster attentional engagement to situational threat words, which is consistent with the findings of Chapman and Martin.

Cognition: Within the cognitive-behavioral model of IBS the way in which the individual reacts cognitively to recurrent GI symptoms and life-events will in turn affect emotional responses, the severity of GI symptoms, and coping ability[94]. The importance of cognitive processes comes from the research showing that patients with IBS are characterized by biases in central processing of visceral stimuli[95]. As previously mentioned, IBS patients show enhanced perceptual responses to visceral sensations. They show a generally negative emotional tendency in their cognitive processing strategies[88] and their dysfunctional cognitions can maintain and exacerbate symptoms[94]. Three dysfunctional cognitions, within a cognitive behavioral framework, seem to be especially important in IBS patients[94]: hypervigilance, somatization and pain catastrophizing.

Hypervigilance relates to selective attention to information that matches the patient’s set of beliefs about his/her disorder. For example, a patient can believe that his/her GI sensations are caused by an organic disease and he/she can consequently show hypervigilance to GI sensations. Bray et al[96] have specified that patients with IBS can express one of the three symptom attributional styles: somatizing attributional style (tendency to interpret symptoms as a physical disorder); psychologizing attributional style (tendency to interpret symptoms as an emotional response to stress); and normalizing attributional style (tendency to interpret symptoms as a normal experience). Contrary to common opinion, they have found that the normalizing style was predominant among IBS patients specifically in those attending general practice compared to patients referred to hospital clinics. The latter usually have more severe symptoms and could be less likely to accept psychological or normalizing explanations of their unexplained symptoms[96]. The concept of attributional style is closely related to the term “subjective theory of illness” or a system of illness-related ideas, convictions and appraisals[97]. The self-regulatory model of Leventhal[98] emphasizes the role of cognitive representations of illness and coping efforts on the patients’ responses to health threats. This model suggests several important cognitive and affective facets of risk perceptions. Leventhal et al[98] have suggested that patients form ideas about their illness around five representation dimensions: identity, causal attributions, expectations of duration, consequences, and perceived control and curability. The search for the origin of the illness, as well as causal attributions, is a main focus of illness representations, which is associated with outcome measures.

Somatization is a widespread clinical phenomenon[99] and concerns the tendency to report multiple unexplained somatic complaints and physical illnesses whose expression can be influenced by stress and negative affect[94,100]. Spiegel et al[100] have emphasized that a significant number of IBS patients have a somatization trait exhibiting one or more related symptoms including functional chest pain, generalized weakness, numbness or tingling. This trait is expressed in a wide range of alterations, which include increased cognitive (e.g., hypervigilance), affective (e.g., fear), and behavioral (e.g., health care seeking) responses to physical sensations[100].

Pain catastrophizing is the tendency to ruminate, magnify, or feel helpless about pain[94,101] and is conceptualized as a negative cognitive-affective response to anticipated or actual pain[102]. Catastrophic thinking specific to pain has been linked to GI symptom severity and has been identified as a key cognitive variable mediating the link between depression and the experience of pain in IBS patients[94,95].

The relationship between cognitions and pain is bidirectional; in other words, cognitive processes can influence pain and pain perception, but pain can disrupt cognitive processes as well[94,103]. Cognitive processes, such as appraisals, can play a significant role in the modulation of visceral pain[94], therefore, it is not surprising that CBT can have beneficial effects for patients with IBS.

Kennedy et al[94,103] postulated a hypothesis that IBS is a disorder associated with cognitive impairment and revealed interesting findings about the impact of IBS on cognition. They assessed several cognitive domains including reversal learning and attentional flexibility, selective attention and response inhibition, working memory, and visuospatial episodic memory. The results showed that patients with IBS exhibit a deficit in visuospatial episodic memory functioning due to the negative impact of HPA axis dysregulation on hippocampus-mediated cognitive performance. The authors hypothesized that visuospatial memory impairment may be a common component of IBS. Of course, as the authors stated, there is a need for further investigation in order to identify the neurobiological mechanisms influencing cognitive performance in this group of patients.

Illness behavior: Cognitive interpretations of symptoms influenced by stress and social support availability, may lead to alterations in patient behavior. The behavior in which patients engage to decrease or avoid symptoms includes health care seeking, avoidance behavior, and maladaptive behavioral coping strategies. The use of coping strategies has already been described in relation to social support and is not repeated here. Health care seeking behavior refers to physician visits and frequent somatic complaints. IBS patients have more frequent visits to the physician and are more likely to consult for minor illnesses than patients with peptic ulcer[104]. In a population sample, persons with bowel dysfunction have reported more frequent visits to the physician and more non-GI symptoms than persons without bowel dysfunction. They are also more likely to visit a physician for those non-GI symptoms, and have reported that they view their colds and influenza-like illnesses as more serious than those of other people[105]. IBS patients who frequently consult a physician do not differ from IBS non-consulters in levels of mental distress or chronic stress, however they report significantly higher GI symptom intensity[106]. Even children of IBS patients have more physician visits than children of healthy persons, both for GI and non-GI symptoms. Although frequent GI complaints in children whose parents have IBS are not explained by the parent’s biased perceptions, it seems that parental IBS status and their solicitous responses have independent effects on the child’s symptom complaints[107].

Avoidance behavior has not been measured directly in IBS patients, but data from treatment studies suggest targeting cognitive and behavioral factors can improve IBS symptoms[108,109]. Based on clinical practice experiences we can list common behavior reported by IBS patients, which can roughly be divided into avoidance and control behavior. Avoidance behavior includes activities such as avoiding exercise, food, sex, work and social situations, while control behavior includes checking for blood in stools, wearing baggy clothes when bloated, having medications on hand, and similar types of behavior[109]. The patients use control and avoidance behavior in an attempt to gain control over their symptoms, reduce their intensity, or avoid possible embarrassing consequences that they might have. Unfortunately, this behavior perpetuates the symptoms and overall, they are not beneficial for the patient[108].

Bowel inflammation: Numerous studies have investigated the presence of inflammatory cell activity in IBS patients. There is evidence to support the existence of mild inflammation, at least in a subgroup of IBS patients. For instance, there is evidence of elevated blood levels of T lymphocyte activity markers, increased counts of intraepithelial lymphocytes in some areas of the colon, increased T lymphocyte counts in the lamina propria of the rectum[110], as well as elevated counts and activation of mast cells in the jejunum[111], with indications that mast cell activation near nerve endings seems to be correlated with the severity and frequency of abdominal pain[112].

One of the most frequently used markers of bowel inflammation is fecal calprotectin. In general, patients with IBS express negative or clinically insignificant levels of calprotectin, which makes this marker a valuable tool for differentiating between IBD and IBS. Research shows that compared to IBD patients, IBS patients have significantly lower levels of calprotectin[113-115] while no differences in calprotectin are found when comparing them to healthy persons[113,115,116]. In a study investigating the differences between IBD patients in remission with and without IBS-like symptoms, fecal calprotectin was significantly higher in those with IBS-like symptoms[117], connecting IBS-like symptoms to microscopic inflammation in the absence of structural disease[118]. Also, there are indications that calprotectin is a good predictor of the physical component of HRQoL in IBS patients[119], with patients of low HRQoL showing higher calprotectin levels although no patients had clinically significant values of calprotectin.

HPA axis and hormonal changes: Neurobiological models of IBS point out alterations in neuroendocrine circuits as well as autonomic nervous system, which result in maladaptive responsiveness to various stressors[120]. Stress reactions include the activation of the HPA axis. In short, the perception of physical or psychological stress results in HPA axis activation, leading to increased secretion of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which stimulates the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the anterior pituitary, resulting in increased cortisol secretion from the adrenal cortex. Some studies support the concept of a dysregulated HPA axis system in IBS patients[95,120]. For example, Hellhamer and Hellhamer[35] have listed IBS among disorders with a hypoactive HPA axis. Such hypocortisolemic disorders are characterized by a triad of symptoms: fatigue, pain and stress sensitivity. Hellhamer and Wade[121] have postulated a two-stage model of such disorders: first, chronic stress results in prolonged hypercortisolism that later develops into hypocortisolism. In such circumstances the adrenal glands remain hypertrophic but secrete lower levels of cortisol.

The connection between low cortisol levels and symptoms of pain is the impact of cortisol on prostaglandins, important mediators in pain perception. They sensitize peripheral and central pain receptors, while cortisol has a suppressive effect on their secretion. Prostaglandins also contribute to illness response characterized by elevated body temperature, altered mood, fatigue and hyperalgesia[35].

Generally, several different hypotheses have been proposed about the relationship between HPA axis dysfunction and IBS. One of them is that elevated immune activity and resulting elevated cytokine levels stimulate the HPA axis, resulting in its hypersensitivity. However, although some studies have reported elevated basal plasma cortisol levels in patients with IBS compared to healthy persons[122], others show lower salivary and plasma cortisol levels[123] pointing to a decreased HPA axis reactivity[124]. A possible explanation for such contradictory results is the possibility that the type of hormonal dysregulation (reduced or elevated cortisol levels) depends on the predominant symptoms a patient is experiencing. It seems that functional pain symptoms are related to reduced cortisol secretion while depressive symptoms are related to elevated cortisol secretion[124]. In support of this assumption, Ehlert et al[124] found elevated cortisol levels and a hypersensitive HPA axis in a group of patients with FGIDs who expressed higher depression and anxiety, and found a hypofunctional HPA axis in a group of patients with high somatization levels. It would also seem that patients with a faster resolution of cortisol to basal values express milder symptoms and higher QoL scores[125]. Some studies have indicated that individuals who experience early adverse life events have higher cortisol levels after exposure to a visceral stressor. However, HPA axis hypersensitivity as a reaction to a visceral stressor is under the influence of early stressful experiences rather than IBS diagnosis per se[125].

In addition to cortisol, sex hormones can also modify the perception of visceral sensations and pain, but considering the many interactions female sex hormones have with pain pathways, the underlying mechanisms are difficult to define. Women with IBS have a lower pain threshold during rectal distension[124,126-128] compared to men with IBS and healthy women, while there are no sex differences among healthy subjects or among men with and without IBS[122]. When rectal sensitivity is compared across the phases of the menstrual cycle, results indicate that women with IBS are more sensitive during menstruation, which is not the case in healthy women[129,130].Nevertheless, upon repeated noxious stimuli (rectosigmoid distension), even healthy women show visceral sensitization or heightened perceptual responses[122]. These findings indicate that there is a possible role of female sex hormones in increased pain perception. Many women with IBS report symptom flare-ups in the perimenstrual and perimenopausal phases and symptom fluctuations during their menstrual cycles[131-133]. Some studies have shown that the time of menses is associated with looser stools compared with follicular and luteal phases[133,134]. Additionally, IBS is diagnosed more often in women with dysmenorrhea than in those with a normal cycle[135]. It is possible that hormonal disparities and fluctuations may be responsible for differences in IBS prevalence and symptom presentation among women and between women and men[136-138].

Research on sex differences in HPA axis reactivity shows that even though men express higher cortisol and ACTH levels after psychological distress, women express higher cortisol level as a reaction to opioid antagonist administration on CRH neurons. It is possible that sex hormones influence opioid regulation of the HPA axis. CRH neurons receive inhibitory information from neurons producing β endorphins through μ-opioid receptors. The expression of μ-opioid receptors in the rat brain is modulated by steroid hormones while estrogen stimulates opioid secretion. If we apply these findings to human physiology, then we can explain the absence of differences in cortisol levels after stress exposure between men and women in the luteal phase as well as the findings about the hypoactivity of the HPA axis in women in the follicular phase compared to men[139]. Despite the inconsistencies in research findings, sex differences in HPA axis sensitivity are another possible reason for a higher prevalence of women in the IBS population.

To conclude, results assessing neuroendocrine responses in IBS patients are mixed, depending on the patient’s life history and affective status[120].

Autonomic dysfunction: It is believed that the variability of the dynamic balance of the sympathetic and the parasympathetic systems is the basis for the preservation of stability and health, in other words, that the variable conditions in the environment favor patterns of variability instead of static levels. In line with this assumption, an autonomic imbalance in which one system dominates over the other leads to a decrease in dynamic flexibility and negative health outcomes[140]. The hypothesis about the relationship of parasympathetic hypoactivity and FGIDs has been present for a long time. Even Tougas[141] has suggested that low vagal tone along with sympathetic hyperactivity alters visceral perception. Although research has generally shown altered autonomic function in IBS patients, the findings have been inconsistent. Some researchers[69] have observed increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic activity in IBS patients, while others[142,143] have found this pattern to be typical for constipation-predominant IBS (IBS-C) patients, and the opposite pattern typical in diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D) patients[142]. A study by Elsenbruch and Orr[144] found differences in postprandial autonomic activity depending on IBS subtype. IBS-D patients show a postprandial sympathetic dominance, which is the result of parasympathetic depression rather than sympathetic activation. The change in parasympathetic activity is related to reports of postprandial symptom exacerbation. These alterations are not found in IBS-C patients or healthy subjects, although IBS-C patients also report postprandial symptom exacerbation. These results have to be regarded with caution, as pointed out in a meta-analysis performed by Tak et al[145]. The authors reviewed 14 studies of autonomic activation in functional bowel disease patients and found that research shows they have lower parasympathetic activation compared to healthy subjects, but also that IBS subtypes cannot be differentiated based on that activation. The included studies, however, varied greatly in quality, so the authors concluded that autonomic dysfunction in IBS patients at this moment cannot be confirmed or disputed[145].

Altered gut microbiota: Considering that the human microbiota in adults is stable over time it is interesting to note that IBS patients show higher variability and quantitative composition of the microbiota compared to healthy persons[146,147]. Research on fecal microbiota in IBS patients indicates reduced levels of fecal lactobacilli[148] and bifidobacteria[148-151]. Some research[152] has shown decreased levels of lactobacilli in IBS-D patients, while other studies[153] have found increased levels of lactobacilli in that subgroup of IBS patients. This inconsistency can be the result of different molecular methods used, as well as the result of unstable symptoms in patients samples, diet or the high variability of microbiota in IBS patients[154].

Abdominal pain: Abdominal pain is a common and most disturbing symptom in FGID such as IBS. It seems that the evaluation of abdominal pain is altered in IBS and this may be attributable to affective disturbances, negative emotions and cognitions in anticipation of or during visceral stimulation and altered pain-related expectations[2]. Dissection of pathways linking higher cortical function with emotional, attentional and perceptual factors to the final expression of symptoms is the key to our understanding of pain mechanism underlying IBS[155].

Dorn et al[156] have reported that IBS patients show an increased tendency to report pain, but similar neurosensory sensitivity compared to controls, and this tendency is correlated with psychological distress.

The CBT model of IBS also serves as a framework for describing the vicious circle of symptom generation and perpetuation, based upon the feedback loops between the underlying processes.

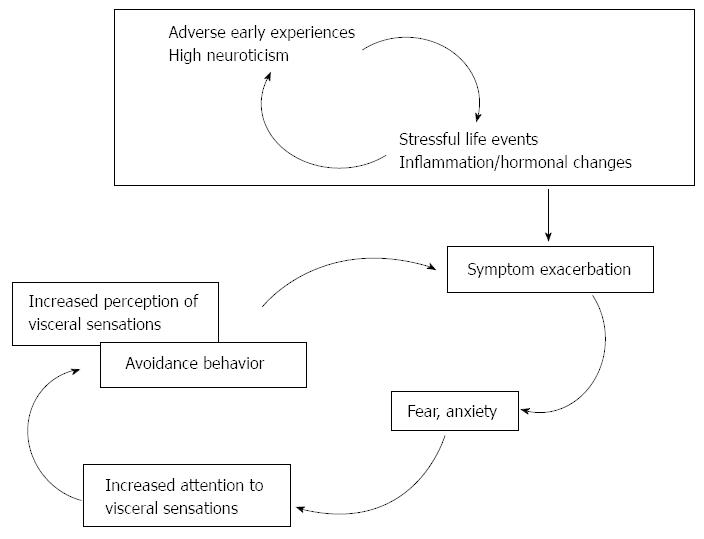

Therefore, we propose the IBS symptom perpetuation model (Figure 2) attempting to explain the factors contributing to symptom maintenance. The novel aspect introduced by this model is the identification of key elements which drive the vicious circle of symptom exacerbation. These key elements (attention to visceral sensation, trait anxiety, visceral anxiety and anxiety sensitivity) should be the target of psychosocial interventions.

Building upon genetic predispositions that include several possible gene polymorphisms and personality traits, primarily neuroticism, early adverse events create a baseline sensitive to further adversities. This baseline is heterogeneous among IBS patients, namely because the personal histories of patients in combination with their genetic makeup create individual patterns with a wide range of variation. What the patients do share is the hypersensitivity resulting from their altered psychophysiological baseline. Hypersensitivity to stress manifested by increased limbic system reactivity can be directly associated with increased perception of and responses to visceral sensations via inappropriate upregulation of pain facilitation systems[18,22].

Precipitating events, usually stressful life events, trigger the onset of symptoms that are then a subject of cognitive interpretations resulting in affective disturbances, primarily anxiety, visceral anxiety and anxiety sensitivity. These disturbances alter cognitive interpretations increasing the perception of the symptoms themselves, and alter illness beliefs that lead to avoidance behavior. Such cognitive alterations can lead to symptom exacerbation and long-term symptom perpetuation.

We consider increased attention to visceral sensation and different manifestations of anxiety to be key components that could lead to symptom exacerbation (abdominal pain and associated bowel disturbances) as illustrated in Figure 2. Anxiety can serve as a mediator between symptom maintenance and altered attention that finally leads to increased perception of visceral sensation and avoidance behavior. Should we conclude that this explanation of symptom maintenance applies to all IBS patients? Of course not. Those patients who express higher trait neuroticism are more prone to interpret even mild somatic changes as serious symptoms and to respond anxiously in such situations. This heightened anxiety can lead to increased attention to and perception of visceral sensations and consequently to symptom exacerbation. The patients aim to reduce discomfort and accompanying negative feelings by avoiding the situations they perceive as threatening. As a result of such individual differences, related to the contribution of predisposing and precipitating factors to symptom maintenance, an integrative analysis of psychological, biological and symptom measures should be performed for each patient as a part of a systematic clinical translational approach, as suggested by Hellhamer and Hellhamer[35]. This is a way to get an estimate of each patient’s status by assuming a concurrent effect of biological, psychological and social factors on disorder expression and persistence.

Based on the described components of the self-maintaining circle it can be assumed that by changing behavior and/or cognition through various psychotherapeutic approaches, primarily the cognitive-behavioral, it is possible to change affective states, which in turn might reduce symptoms and improve the patients’ overall QoL. This assumption is based on the core premise of the CBT approach that physiological, cognitive/affective and behavioral responses are interdependent and responsible for maintaining the disorder[108]. For this reason, changing cognitions (e.g., reinterpreting symptoms or redirecting attention), behavior (e.g., exposure to threatening stimuli or situations followed by a positive outcome), or both may indirectly reduce anxiety and lead to an improvement in symptoms. David and Szentagotai[157] have proposed a cognitive framework that incorporates the constructs of cognitive psychology into the CBT approach. It is a general model that can be adapted for specific clinical problems, such as IBS. There are seven steps one should take into account when approaching the key elements of the self-maintaining circle of IBS: (1) the covert stimulus (e.g., bodily sensations, such as GI symptoms, emotional arousal, memories and anticipation); (2) input and selection (e.g., patients tend to selectively attend to GI stimuli); (3) perception and symbolic representation of the stimulus (definitions and descriptions of the stimulus, e.g., they may interpret symptoms as a physical disorder or as an emotional response to stress); (4) nonevaluative interpretation of the symbolic representation of the stimuli (inferences about unobserved aspects of the perceived stimulus; e.g., the patient could ruminate “I worry that symptoms could appear suddenly”); (5) evaluative interpretations of processed stimuli (non-neutral appraisals of stimuli or images that can be conscious or unconscious; e.g., “If my symptoms appeared suddenly, I could be embarrassed”); (6) emotional response to processed stimuli (arousal, worry and anxiety); and (7) coping mechanisms to feelings arising from response to stimuli (e.g., patients could try to eliminate what they evaluate negatively, either by avoidance or escape). Psychotherapists can intervene at any point based on each patient’s status.

In conclusion, the CBT model of IBS provides not only a useful overview of the interactions between psychological and biological processes underlying IBS symptoms but also gives an effective treatment for alleviating these symptoms.

P- Reviewers: Bevan JL, Becker S, Trinkley KE S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Kerr C E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Porcelli P, Todarello O. Psychological factors affecting functional gastrointestinal disorders. Psychological factors affecting medical conditions. A new classification for DSM-V. Adv Psychosom Med. Basel: Karger 2007; 34-56. |

| 2. | Elsenbruch S. Abdominal pain in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: a review of putative psychological, neural and neuro-immune mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:386-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Spiller R, Aziz Q, Creed F, Emmanuel A, Houghton L, Hungin P, Jones R, Kumar D, Rubin G, Trudgill N. Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. Gut. 2007;56:1770-1798. [PubMed] |

| 4. | van der Veek PP, Dusseldorp E, van Rood YR, Masclee AA. Testing a biobehavioral model of irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:412-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fichna J, Storr MA. Brain-Gut Interactions in IBS. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129-136. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Lutgendorf SK, Costanzo ES. Psychoneuroimmunology and health psychology: an integrative model. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17:225-232. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Drossman DA. Chronic functional abdominal pain. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2270-2281. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Drossman DA. Presidential address: Gastrointestinal illness and the biopsychosocial model. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:258-267. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Mayer EA, Collins SM. Evolving pathophysiologic models of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:2032-2048. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Spence MJ. A prospective investigation of cognitive-behavioural models of irritable bowel and chronic fatigue syndromes: Implications for theory, classification and treatment. New Zealand: The University of Auckland 2005; . |

| 12. | Naliboff BD, Munakata J, Fullerton S, Gracely RH, Kodner A, Harraf F, Mayer EA. Evidence for two distinct perceptual alterations in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 1997;41:505-512. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Yunus MB. Fibromyalgia and overlapping disorders: the unifying concept of central sensitivity syndromes. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;36:339-356. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Dantzer R. Somatization: a psychoneuroimmune perspective. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:947-952. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Rief W, Barsky AJ. Psychobiological perspectives on somatoform disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:996-1002. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Brown RJ. Psychological mechanisms of medically unexplained symptoms: an integrative conceptual model. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:793-812. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Fink P, Rosendal M, Toft T. Assessment and treatment of functional disorders in general practice: the extended reattribution and management model--an advanced educational program for nonpsychiatric doctors. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:93-131. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Keough ME, Timpano KR, Zawilinski LL, Schmidt NB. The association between irritable bowel syndrome and the anxiety vulnerability factors: body vigilance and discomfort intolerance. J Health Psychol. 2011;16:91-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Creed F. Cognitive behavioural model of irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2007;56:1039-1041. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Deary V, Chalder T, Sharpe M. The cognitive behavioural model of medically unexplained symptoms: a theoretical and empirical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:781-797. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Spence MJ, Moss-Morris R. The cognitive behavioural model of irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective investigation of patients with gastroenteritis. Gut. 2007;56:1066-1071. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Naliboff BD, Fresé MP, Rapgay L. Mind/Body psychological treatments for irritable bowel syndrome. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2008;5:41-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rowlands L. The effect of perceptual training on somatosensory distortion in physical symptom reporters. Manchester: University of Manchester 2011; 129. |

| 24. | Reme SE, Stahl D, Kennedy T, Jones R, Darnley S, Chalder T. Mediators of change in cognitive behaviour therapy and mebeverine for irritable bowel syndrome. Psychol Med. 2011;41:2669-2679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Beck AT. The current state of cognitive therapy: a 40-year retrospective. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:953-959. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Lahey BB. Public health significance of neuroticism. Am Psychol. 2009;64:241-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1135] [Cited by in RCA: 1031] [Article Influence: 64.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tkalcić M, Hauser G, Stimac D. Differences in the health-related quality of life, affective status, and personality between irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:862-867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kalantar JS, Locke GR, Zinsmeister AR, Beighley CM, Talley NJ. Familial aggregation of irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective study. Gut. 2003;52:1703-1707. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Saito YA, Zimmerman JM, Harmsen WS, De Andrade M, Locke GR, Petersen GM, Talley NJ. Irritable bowel syndrome aggregates strongly in families: a family-based case-control study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:790-797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hotoleanu C, Popp R, Trifa AP, Nedelcu L, Dumitrascu DL. Genetic determination of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6636-6640. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Fukudo S, Kanazawa M. Gene, environment, and brain-gut interactions in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26 Suppl 3:110-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Camilleri M, Andrews CN, Bharucha AE, Carlson PJ, Ferber I, Stephens D, Smyrk TC, Urrutia R, Aerssens J, Thielemans L. Alterations in expression of p11 and SERT in mucosal biopsy specimens of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:17-25. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Coates MD, Mahoney CR, Linden DR, Sampson JE, Chen J, Blaszyk H, Crowell MD, Sharkey KA, Gershon MD, Mawe GM. Molecular defects in mucosal serotonin content and decreased serotonin reuptake transporter in ulcerative colitis and irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1657-1664. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Kapeller J, Houghton LA, Mönnikes H, Walstab J, Möller D, Bönisch H, Burwinkel B, Autschbach F, Funke B, Lasitschka F. First evidence for an association of a functional variant in the microRNA-510 target site of the serotonin receptor-type 3E gene with diarrhea predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2967-2977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Hellhamer DH, Hellhamer J. Stress. The brain-body connection. Basel: Karger 2008; . |

| 36. | Creed FH, Levy R, Bradley L, Drossman DA, Francisconi C, Naliboff BD, Olden KW. Psychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Rome III: The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. McLean, VA: Degnon Associates Inc 2006; 295-368. |

| 37. | Drossman DA, Leserman J, Nachman G, Li ZM, Gluck H, Toomey TC, Mitchell CM. Sexual and physical abuse in women with functional or organic gastrointestinal disorders. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:828-833. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Gastrointestinal tract symptoms and self-reported abuse: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1040-1049. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Leserman J, Drossman DA. Relationship of abuse history to functional gastrointestinal disorders and symptoms: some possible mediating mechanisms. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8:331-343. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Chang L. The role of stress on physiologic responses and clinical symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:761-765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Bradford K, Shih W, Videlock EJ, Presson AP, Naliboff BD, Mayer EA, Chang L. Association between early adverse life events and irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:385-90.e1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Zarpour S, Besharat MA. Comparison of Personality Characteristics of Individuals with Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Healthy Individuals. In: Öngen DE, H㉨rsen C, Halat M, Boz H, editors. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. Proceedings of the 2nd World Conference on Psychology, Counselling and Guidance; 2011; Elsevier, 2011: 84-88. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Farnam A, Somi MH, Sarami F, Farhang S, Yasrebinia S. Personality factors and profiles in variants of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:6414-6418. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Farnam A, Somi MH, Sarami F, Farhang S. Five personality dimensions in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4:959-962. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Hazlett-Stevens H, Craske MG, Mayer EA, Chang L, Naliboff BD. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome among university students: the roles of worry, neuroticism, anxiety sensitivity and visceral anxiety. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55:501-505. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Tanum L, Malt UF. Personality and physical symptoms in nonpsychiatric patients with functional gastrointestinal disorder. J Psychosom Res. 2001;50:139-146. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Tkalčić M, Hauser G, Pletikosić S, Štimac D. Personality in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel diseases. Clujul Medical. 2009;82:577-580. |

| 48. | Tosic-Golubovic S, Miljkovic S, Nagorni A, Lazarevic D, Nikolic G. Irritable bowel syndrome, anxiety, depression and personality characteristics. Psychiatr Danub. 2010;22:418-424. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Zargar Y, Davoudi I, Fatahinia M, Masjedizadeh AR. Comparison of personality traits of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients and healthy population with control of mental health in Ahvaz. J Sci Med. 2010;10:131-139. |

| 50. | Costa PT, McCrae RR. Neuroticism, somatic complaints, and disease: is the bark worse than the bite? J Pers. 1987;55:299-316. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Tanum L, Malt UF. Personality traits predict treatment outcome with an antidepressant in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorder. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:935-941. [PubMed] |

| 52. | Dinan TG, O’Keane V, O’Boyle C, Chua A, Keeling PW. A comparison of the mental status, personality profiles and life events of patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991;84:26-28. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Blanchard EB. Irritable bowel syndrome: Psychosocial assessment and treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association 2001; . |

| 54. | Okami Y, Kato T, Nin G, Harada K, Aoi W, Wada S, Higashi A, Okuyama Y, Takakuwa S, Ichikawa H. Lifestyle and psychological factors related to irritable bowel syndrome in nursing and medical school students. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1403-1410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Halpert A, Drossman D. Biopsychosocial issues in irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:665-669. [PubMed] |

| 56. | Drossman DA, McKee DC, Sandler RS, Mitchell CM, Cramer EM, Lowman BC, Burger AL. Psychosocial factors in the irritable bowel syndrome. A multivariate study of patients and nonpatients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:701-708. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Remes Troche JM, Torres-Aguilera M, De la Cruz Patińo E, Azamar Jacome AA, Roesch FB. Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) Among Caregivers of Chronically Ill Patients: Prevalence, Quality of Life (QOL) and Association With Psychological Stress. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:S-383. |

| 58. | Blanchard EB, Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Rowell D, Carosella AM, Powell C, Sanders K, Krasner S, Kuhn E. The role of stress in symptom exacerbation among IBS patients. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:119-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Whitehead WE, Crowell MD, Robinson JC, Heller BR, Schuster MM. Effects of stressful life events on bowel symptoms: subjects with irritable bowel syndrome compared with subjects without bowel dysfunction. Gut. 1992;33:825-830. [PubMed] |

| 60. | Pace F, Molteni P, Bollani S, Sarzi-Puttini P, Stockbrügger R, Bianchi Porro G, Drossman DA. Inflammatory bowel disease versus irritable bowel syndrome: a hospital-based, case-control study of disease impact on quality of life. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1031-1038. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Cohen S. Social relationships and health. Am Psychol. 2004;59:676-684. [PubMed] |

| 62. | Hudek-Knežević J, Kardum I. Stres i tjelesno zdravlje. Jastrebarsko: Naklada Slap 2006; . |

| 63. | Lakey B, Cohen S. Social support theory and measurement. Measuring and intervening in social support. New York: Oxford University Press 2000; . |

| 64. | Jones MP, Wessinger S. Small intestinal motility. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006;22:111-116. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Gerson MJ, Gerson CD, Awad RA, Dancey C, Poitras P, Porcelli P, Sperber AD. An international study of irritable bowel syndrome: family relationships and mind-body attributions. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:2838-2847. [PubMed] |

| 66. | Lackner JM, Brasel AM, Quigley BM, Keefer L, Krasner SS, Powell C, Katz LA, Sitrin MD. The ties that bind: perceived social support, stress, and IBS in severely affected patients. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:893-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Sewitch MJ, Abrahamowicz M, Bitton A, Daly D, Wild GE, Cohen A, Katz S, Szego PL, Dobkin PL. Psychological distress, social support, and disease activity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1470-1479. [PubMed] |

| 68. | Pellissier S, Dantzer C, Canini F, Mathieu N, Bonaz B. Psychological adjustment and autonomic disturbances in inflammatory bowel diseases and irritable bowel syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:653-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Crane C, Martin M. Social learning, affective state and passive coping in irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26:50-58. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Swickert RJ, Hittner JB, Foster A. Big Five traits interact to predict perceived social support. Pers Indiv Differ. 2010;48:736-741. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Cho HS, Park JM, Lim CH, Cho YK, Lee IS, Kim SW, Choi MG, Chung IS, Chung YK. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut Liver. 2011;5:29-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Quigley EM. Irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease: interrelated diseases? Chin J Dig Dis. 2005;6:122-132. [PubMed] |

| 73. | Sugaya N, Nomura S. Relationship between cognitive appraisals of symptoms and negative mood for subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome. Biopsychosoc Med. 2008;2:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Kovács Z, Kovács F. Depressive and anxiety symptoms, dysfunctional attitudes and social aspects in irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2007;37:245-255. [PubMed] |

| 75. | Nicholl BI, Halder SL, Macfarlane GJ, Thompson DG, O’Brien S, Musleh M, McBeth J. Psychosocial risk markers for new onset irritable bowel syndrome--results of a large prospective population-based study. Pain. 2008;137:147-155. [PubMed] |

| 76. | Simrén M, Axelsson J, Gillberg R, Abrahamsson H, Svedlund J, Björnsson ES. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease in remission: the impact of IBS-like symptoms and associated psychological factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:389-396. [PubMed] |

| 77. | Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel H. Medically unexplained physical symptoms, anxiety, and depression: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:528-533. [PubMed] |

| 78. | Gros DF, Antony MM, McCabe RE, Swinson RP. Frequency and severity of the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome across the anxiety disorders and depression. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23:290-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Deacon BJ, Abramowitz JS, Woods CM, Tolin DF. The Anxiety Sensitivity Index - Revised: psychometric properties and factor structure in two nonclinical samples. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:1427-1449. [PubMed] |

| 80. | Labus JS, Mayer EA, Chang L, Bolus R, Naliboff BD. The central role of gastrointestinal-specific anxiety in irritable bowel syndrome: further validation of the visceral sensitivity index. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:89-98. [PubMed] |

| 81. | Labus JS, Bolus R, Chang L, Wiklund I, Naesdal J, Mayer EA, Naliboff BD. The Visceral Sensitivity Index: development and validation of a gastrointestinal symptom-specific anxiety scale. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:89-97. [PubMed] |

| 82. | Afzal M, Potokar JP, Probert CS, Munafò MR. Selective processing of gastrointestinal symptom-related stimuli in irritable bowel syndrome. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:758-761. [PubMed] |

| 83. | Azpiroz F. Gastrointestinal perception: pathophysiological implications. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2002;14:229-239. [PubMed] |

| 85. | Kilpatrick LA, Ornitz E, Ibrahimovic H, Treanor M, Craske M, Nazarian M, Labus JS, Mayer EA, Naliboff BD. Sex-related differences in prepulse inhibition of startle in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Biol Psychol. 2010;84:272-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Musial F, Häuser W, Langhorst J, Dobos G, Enck P. Psychophysiology of visceral pain in IBS and health. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:589-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Mogg K, Bradley BP. A cognitive-motivational analysis of anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36:809-848. [PubMed] |

| 89. | Mathews A, Mackintosh B. A cognitive model of selective processing in anxiety. Cognit Ther Res. 1998;22:539-560. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 90. | Lackner JM, Lou Coad M, Mertz HR, Wack DS, Katz LA, Krasner SS, Firth R, Mahl TC, Lockwood AH. Cognitive therapy for irritable bowel syndrome is associated with reduced limbic activity, GI symptoms, and anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:621-638. [PubMed] |

| 91. | Martin M, Chapman SC. Cognitive processing in putative functional gastrointestinal disorder: rumination yields orientation to social threat not pain. Eur J Pain. 2010;14:207-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Chapman S, Martin M. Attention to pain words in irritable bowel syndrome: increased orienting and speeded engagement. Br J Health Psychol. 2011;16:47-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Tkalcic M, Domijan D, Pletikosic S, Setic M, Hauser G. Attentional biases in irritable bowel syndrome patients. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2014;In press. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Kennedy PJ, Clarke G, Quigley EM, Groeger JA, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Gut memories: towards a cognitive neurobiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:310-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Lackner JM, Quigley BM, Blanchard EB. Depression and abdominal pain in IBS patients: the mediating role of catastrophizing. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:435-441. [PubMed] |

| 96. | Bray BD, Nicol F, Penman ID, Ford MJ. Symptom interpretation and quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56:122-126. [PubMed] |

| 97. | Riedl A, Maass J, Fliege H, Stengel A, Schmidtmann M, Klapp BF, Mönnikes H. Subjective theories of illness and clinical and psychological outcomes in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:449-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Leventhal H, Benyamini Y, Brownlee S. Illness representations: theoretical foundations. Perceptions of Health and Illness. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic 1997; 19-45. |

| 99. | Porcelli P, Sonino N, editors . Psychological factors affecting medical conditions. A new classification for DSM-V. Adv Psychosom Med. Basel: Karger 2007; . |

| 100. | Spiegel BM, Kanwal F, Naliboff B, Mayer E. The impact of somatization on the use of gastrointestinal health-care resources in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2262-2273. [PubMed] |

| 101. | Sullivan MJ, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, Keefe F, Martin M, Bradley LA, Lefebvre JC. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin J Pain. 2001;17:52-64. [PubMed] |

| 102. | Quartana PJ, Campbell CM, Edwards RR. Pain catastrophizing: a critical review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:745-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 766] [Cited by in RCA: 936] [Article Influence: 58.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Kennedy PJ, Clarke G, O’Neill A, Groeger JA, Quigley EM, Shanahan F, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Cognitive performance in irritable bowel syndrome: evidence of a stress-related impairment in visuospatial memory. Psychol Med. 2013;Aug 29; Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] |

| 104. | Whitehead WE, Winget C, Fedoravicius AS, Wooley S, Blackwell B. Learned illness behavior in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer. Dig Dis Sci. 1982;27:202-208. [PubMed] |

| 105. | Sandler RS, Drossman DA, Nathan HP, McKee DC. Symptom complaints and health care seeking behavior in subjects with bowel dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:314-318. [PubMed] |

| 106. | Gulewitsch MD, Enck P, Schwille-Kiuntke J, Weimer K, Schlarb AA. Mental Strain and Chronic Stress among University Students with Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:206574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Levy RL, Whitehead WE, Walker LS, Von Korff M, Feld AD, Garner M, Christie D. Increased somatic complaints and health-care utilization in children: effects of parent IBS status and parent response to gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2442-2451. [PubMed] |

| 108. | Kennedy TM, Chalder T, McCrone P, Darnley S, Knapp M, Jones RH, Wessely S. Cognitive behavioural therapy in addition to antispasmodic therapy for irritable bowel syndrome in primary care: randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess. 2006;10:iii-iv, ix-x, 1-67. [PubMed] |

| 109. | Reme SE, Darnley S, Kennedy T, Chalder T. The development of the irritable bowel syndrome-behavioral responses questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69:319-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Ortiz-Lucas M, Saz-Peiró P, Sebastián-Domingo JJ. Irritable bowel syndrome immune hypothesis. Part one: the role of lymphocytes and mast cells. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2010;102:637-647. [PubMed] |

| 111. | Guilarte M, Santos J, de Torres I, Alonso C, Vicario M, Ramos L, Martínez C, Casellas F, Saperas E, Malagelada JR. Diarrhoea-predominant IBS patients show mast cell activation and hyperplasia in the jejunum. Gut. 2007;56:203-209. [PubMed] |

| 112. | Barbara G, De Giorgio R, Stanghellini V, Cremon C, Salvioli B, Corinaldesi R. New pathophysiological mechanisms in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20 Suppl 2:1-9. [PubMed] |

| 113. | El-Badry A, Sedrak H, Rashed L. Faecal calprotectin in differentiating between functional and organic bowel diseases. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2010;11:70-73. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Schoepfer AM, Trummler M, Seeholzer P, Seibold-Schmid B, Seibold F. Discriminating IBD from IBS: comparison of the test performance of fecal markers, blood leukocytes, CRP, and IBD antibodies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:32-39. [PubMed] |

| 115. | Sydora MJ, Sydora BC, Fedorak RN. Validation of a point-of-care desk top device to quantitate fecal calprotectin and distinguish inflammatory bowel disease from irritable bowel syndrome. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:207-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Erbayrak M, Turkay C, Eraslan E, Cetinkaya H, Kasapoglu B, Bektas M. The role of fecal calprotectin in investigating inflammatory bowel diseases. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2009;64:421-425. [PubMed] |

| 117. | Keohane J, O’Mahony C, O’Mahony L, O’Mahony S, Quigley EM, Shanahan F. Irritable bowel syndrome-type symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a real association or reflection of occult inflammation? Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1788, 1789-194; quiz 1795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |