Published online Jan 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.242

Revised: August 23, 2013

Accepted: September 16, 2013

Published online: January 7, 2014

Processing time: 235 Days and 21.5 Hours

AIM: To compare the diagnostic yield of heterotopic gastric mucosa (HGM) in the cervical esophagus with conventional imaging (CI) and narrow-band imaging (NBI).

METHODS: A prospective study with a total of 760 patients receiving a CI examination (mean age 51.6 years; 47.8% male) and 760 patients undergoing NBI examination (mean age 51.2 years; 45.9% male). The size of HGM was classified as small (1-5 mm), medium (6-10 mm), or large (> 1 cm). A standardized questionnaire was used to obtain demographic characteristics, social habits, and symptoms likely to be related to cervical esophageal HGM, including throat symptoms (globus sensation, hoarseness, sore throat, and cough) and upper esophageal symptoms (dysphagia and odynophagia) at least 3 mo in duration. The clinicopathological classification of cervical esophageal HGM was performed using the proposal by von Rahden et al.

RESULTS: Cervical esophageal HGM was found in 36 of 760 (4.7%) and 63 of 760 (8.3%) patients in the CI and NBI groups, respectively (P = 0.007). The NBI mode discovered significantly more small-sized HGM than CI (55% vs 17%; P < 0.0001). For the 99 patients with cervical esophageal HGM, biopsies were performed in 56 patients; 37 (66%) had fundic-type gastric mucosa, and 19 had antral-type mucosa. For the clinicopathological classification, 77 patients (78%) were classified as HGM I (asymptomatic carriers); 21 as HGM II (symptomatic without morphologic changes); and one as HGM III (symptomatic with morphologic change). No intraepithelial neoplasia or adenocarcinoma was found.

CONCLUSION: NBI endoscopy detects more cervical esophageal HGM than CI does. Fundic-type gastric mucosa constitutes the most common histology. One-fifth of patients have throat or dysphagic symptoms.

Core tip: This prospective study demonstrated the diagnostic yield of narrow-band illumination in the evaluation of cervical esophageal heterotopic gastric mucosa and provided clinicopathological data indicating that most heterotopic gastric mucosa had fundic-type gastric mucosa, with 22% of patients being symptomatic.

- Citation: Cheng CL, Lin CH, Liu NJ, Tang JH, Kuo YL, Tsui YN. Endoscopic diagnosis of cervical esophageal heterotopic gastric mucosa with conventional and narrow-band images. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(1): 242-249

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i1/242.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.242

Heterotopic gastric mucosa (HGM) in the cervical esophagus is a macroscopically pink lesion of congenital origin characterized by the presence of gastric epithelium in the upper esophagus. The clinical significance of these lesions remains unknown. At endoscopy, these HGM areas are typically small, distinct patches in the proximal 3 cm of the esophagus. The reported prevalence of endoscopically diagnosed cervical esophageal HGM using conventional illumination (CI) varies from 1% to 10% in adults[1-7] and 5.9% in children[8]. The wide variation in this frequency appears to be related to anatomical location and inadequate examinations by the endoscopists. Increased awareness of the presence of HGM by the examiner has been shown to increase the endoscopic detection rate[9]. Narrow-band imaging (NBI) is an innovative optical technique that modifies the center wavelength and bandwidth of an endoscope’s light into a narrow band illumination of 415 ± 30 nm. By utilizing this narrow spectrum, the contrast in the capillary pattern of the superficial layer is markedly improved compared to CI[10]. This system is highly applicable in the detection of pre-malignant lesions of the hypo-pharynx, esophagus, stomach, and colon[11,12]. With the NBI contrast, a significant number of patients initially diagnosed with nonerosive reflux disease may be re-categorized as having erosive esophagitis[13]. Furthermore, Hori et al[14] reported that cervical HGM was found in 13.8% of their patients with NBI endoscopy. However, the diagnostic yield of NBI endoscopy over CI endoscopy has not yet been validated.

Because NBI enhances the contrast between the esophageal and gastric mucosa, we hypothesized that the use of this optical technique may increase the detection of cervical esophageal HGM. The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the clinical usefulness of an NBI endoscopy system, compared to the standard CI system, in the diagnosis of cervical esophageal HGM. The secondary aim was to assess the histological and clinical significance of patients with cervical esophageal HGM.

This work was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association. This study was ethically approved by the Institutional Review Board of Evergreen hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan. All patients provided written informed consent.

This was a prospective study, and the study population consisted of patients seen in the gastroenterology clinics of Evergreen Hospital in Taoyuan. Patients undergoing an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for all possible indications, such as symptoms or history suggestive of upper gastrointestinal (GI) disease, were included. Exclusion criteria included an age younger than 18 years, incarceration, and the inability to provide informed consent. All endoscopies were performed by a single experienced endoscopist (CL Cheng). Endoscopies with NBI contrast were performed between April 2011 and March 2012, and endoscopies with CI mode were performed between April 2012 and December 2012. The rationale of this study design was to provide the best detection rate of CI endoscopy, as we believed that the experience obtained during NBI endoscopy could help to improve the endoscopist’s diagnostic ability with CI mode. A standardized questionnaire was used to obtain the demographic characteristics, social habits, medications, and symptoms for each patient. Symptoms likely to be related to cervical HGM, including throat symptoms (globus sensation, hoarseness, sore throat, and cough) and upper esophageal symptoms (dysphagia, odynophagia) at least 3 mo in duration, were noted prior to endoscopy. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was diagnosed using the Montreal definition[15]. Patients who smoked cigarettes or drank alcohol regularly during the 12 mo preceding the interview were considered active smokers or drinkers. All patients signed an informed consent form prior to their inclusion in the study. The data from the questionnaire and the endoscopy were stored in a computerized database. All authors had full access to the study data and had reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

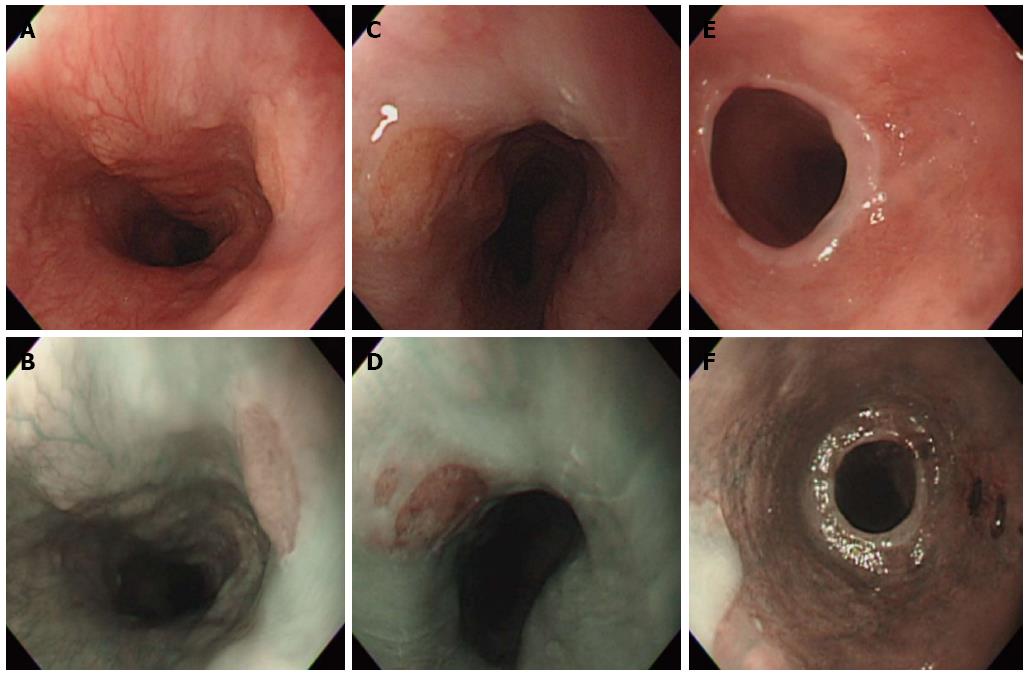

After adequate fasting, a routine EGD was performed with a standard upper endoscopy (GIF-Q260; Olympus Optical Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) using topical anesthesia, with or without conscious sedation, depending on the patient’s preference. Conscious sedation was performed with midazolam (2-5 mg). During all procedures, the esophagus was carefully surveyed, and special attention was paid to the area of the cervical esophagus. A cervical esophageal HGM was diagnosed as well-circumscribed salmon-red (in CI mode) or brownish (in NBI mode) mucosa with a distinct border (Figure 1). The size of the HGM was determined by the top span of the fully open biopsy forceps and was classified as small size (1-5 mm), medium size (6-10 mm), or large size (> 1 cm). One or two biopsies were obtained from the cervical esophageal HGM whenever possible. Pathological examination was performed to determine the type of gastric mucosa and to evaluate the presence of intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori). Fundic-type HGM was defined by the presence of both parietal cells and chief cells, and antral-type HGM was defined by the absence of chief cells and only a few parietal cells. Dysplasia was defined as neoplastic epithelium that remained confined within the basement membrane of the epithelial surface from which it arose. The presence of H. pylori in the HGM was identified using hematoxylin-eosin stain. Reflux esophagitis was graded with the Los Angeles classification[16]. Barrett’s esophagus was considered when the maximal extent of the columnar-lined mucosa in the distal esophagus was 10 mm or more of the length from the gastroesophageal junction; it was diagnosed when the specialized intestinal metaplasia was confirmed histologically. A hiatal hernia was considered present if the maximal length of the gastric folds above the diaphragm was 20 mm or more during quiet respiration. Gastric and duodenal ulcers were defined as breaks in the epithelium with an appreciable depth and a diameter of at least 5 mm.

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 13.0 software for Windows XP. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables were compared using Student’s t test and univariate analysis. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. In a multivariate logistic regression, the presence of throat or upper esophageal symptoms was chosen as the outcome variable. The odds ratios and their corresponding 95%CI served to describe the strength of the influence exerted by the retained predictor variable of the multivariate model.

Table 1 presents the demographics of the 2 study arms by age, sex, social habits, and clinical symptoms. There were no differences between the 2 arms with respect to the demographics, social habits, or clinical symptoms before the procedure.

| NBI (n = 760) | CI (n = 760) | P value | |

| Men | 349 (46) | 363 (48) | 0.50 |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 51.2 ± 15.3 | 51.6 ± 13.7 | 0.58 |

| Social habits | |||

| Alcohol use | 75 (10) | 56 (7) | 0.10 |

| Smoking | 161 (21) | 176 (23) | 0.92 |

| Clinical symptoms | |||

| Reflux symptoms | 260 (34) | 240 (32) | 0.30 |

| Throat symptoms | 61 (8) | 64 (8) | 0.85 |

| Dysphagia | 16 (2.1) | 12 (1.6) | 0.57 |

Table 2 presents the endoscopic findings in the 2 arms of the study. The detection rate of cervical esophageal HGM in the NBI arm was 8.3% and that in the CI arm was 4.7% (P = 0.007). There were no differences between the 2 arms in the other endoscopic findings, except for gastric ulcers, which were found in 9.9% and 14.3% of the NBI and CI arms, respectively (P = 0.009).

| NBI (n = 760) | CI (n = 760) | P value | |

| Conscious sedation for EGD | 400 (53) | 397 (52) | 0.570 |

| Cervical HGM | 63 (8.3) | 36 (4.7) | 0.007 |

| Reflux esophagitis | 158 (21) | 138 (18) | 0.220 |

| Los Angeles grade A-B | 147 (19) | 128 (17) | |

| Los Angeles grade C-D | 11 (1.5) | 10 (1.3) | |

| Barrett’s esophagus | 3 (0.4) | 4 (0.5) | 1.000 |

| Peptic ulcers | 209 (28) | 238 (31) | 0.110 |

| Gastric ulcer | 75 (9.9) | 109 (14.3) | 0.009 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 161 (21) | 183 (24) | 0.200 |

| Hiatus hernia | 33 (4.3) | 37 (4.9) | 0.710 |

Table 3 shows the clinicopathological and endoscopic characteristics of cervical esophageal HGM in the 2 arms of the study. The NBI arm had significantly more small-sized cervical HGM than the CI (54% vs 17%, P < 0.0001). Clinicopathological classification was performed based on the procedure of von Rahden et al[17] There were no differences between the 2 cervical esophageal HGM groups in the clinicopathological or other endoscopic characteristics.

| HGM in NBI (n = 63) | HGM in CI (n = 36) | P value | |

| Clinical characteristics | 0.65 | ||

| HGM type I | 47 (75) | 30 (83) | |

| HGM type II | 15 (24) | 6 (17) | |

| HGM type III | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Number of cervical HGM | 0.25 | ||

| Single | 43 (68) | 28 (78) | |

| Two | 12 (19) | 7 (19) | |

| Three or more | 7 (11.1) | 1 (2.8) | |

| Circumferential | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Smallest size of cervical HGM1 | < 0.0001 | ||

| 0-5 mm | 34 (55) | 6 (17) | |

| 6-10 mm | 24 (39) | 19 (53) | |

| > 1 cm | 4 (6.5) | 11 (30) | |

| Biopsy of cervical HGM | 34 (54) | 22 (61) | |

| Fundic type gastric mucosa | 22 (65) | 15 (68) | |

| Antral type gastric mucosa | 12 (35) | 7 (32) | |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 0 | 0 | |

| Presence of H. pylori | 2 (5.9) | 1 (4.6) | |

| Associated with GERD | 30 (48) | 16 (44) | 0.84 |

| Erosive esophagitis | 17 (27) | 10 (28) | 0.65 |

| Barrett’s esophagus | 0 (0) | 1 (2.8) | 0.37 |

| Associated with hiatus hernia | 4 (6.4) | 3 (8.3) | 0.70 |

| Associated with peptic ulcers | 16 (25) | 11 (31) | 0.64 |

When we combined the data from both arms of the study, 99 patients had cervical esophageal HGM, and 77 patients were classified as HGM type I (asymptomatic carrier); 21 as HGM type II (symptomatic individuals without morphologic change); and one as HGM type III (symptomatic due to morphologic change). The patient with circumferential cervical HGM and upper esophageal stenosis (HGM type III) had presented with chronic dysphagia for many years. Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring using a dual-electrode catheter revealed abnormal proximal acid reflux, with a percentage of esophageal total acid exposure (pH < 4) of 1.4% and a normal distal acid exposure, with a DeMeester score of 2.7. After excluding the possibility of malignancy by biopsy, the dysphagia was well managed with daily esomeprazole 40 mg.

Biopsy specimens were obtained from 56 of the 99 patients with cervical esophageal HGM. Fundic-type gastric mucosa constituted 66% of the cases, and antral-type mucosa comprised the remaining 34%. We did not observe intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia in any of the cases. Infection with H. pylori in the cervical esophageal HGM was identified in 3 patients, and gastric H. pylori infection was positive in all of these patients.

Table 4 presents the difference between patients with and without a cervical esophageal HGM. There were no differences between the 2 groups in demographics or social habits. Throat symptoms were significantly more frequently observed in patients with cervical HGM than in those who did not have cervical HGM (20.2% vs 7.4%, P < 0.0001). There were no differences between the 2 groups in the other clinical manifestations. Erosive esophagitis was also more frequently observed in patients with cervical HGM (27.3% vs 18.9%, P = 0.0488). No significant differences were found with respect to Barrett’s esophagus, hiatal hernias, or peptic ulcers.

| Cases with HGM (n = 99) | Cases without HGM (n = 1421) | P value | |

| Demographics | |||

| Men | 55 (56) | 657 (46) | 0.08 |

| Mean (SD) age (yr) | 51.9 (13.2) | 51.4 (14.6) | 0.74 |

| Social habits | |||

| Alcohol use | 10 (10.1) | 121 (8.5) | 0.58 |

| Smoking | 25 (25) | 312 (22) | 0.45 |

| Clinical symptoms | |||

| Reflux symptoms | 38 (38) | 462 (33) | 0.23 |

| Throat symptoms | 20 (20) | 105 (7.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Dysphagia | 2 (2.0) | 26 (1.8) | 0.70 |

| Conscious sedation | 50 (51) | 747 (53) | 0.76 |

| GERD | 46 (47) | 541 (38) | 0.11 |

| Reflux esophagitis | 27 (27.3) | 269 (18.9) | 0.0488 |

| Los Angeles A-B | 23 (23.2) | 252 (17.7) | |

| Los Angeles C-D | 4 (4.0) | 18 (1.3) | |

| Barrett’s esophagus | 1 (1.0) | 6 (0.4) | 0.38 |

| Peptic ulcers | 27 (27) | 420 (30) | 0.73 |

| Hiatus hernia | 7 (7.1) | 63 (4.4) | 0.21 |

Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the risk factors for the development of throat symptoms and dysphagia in patients with cervical HGM. No independent risk factor was identified by the multivariate model.

In this report, we describe an observational study comparing the use of NBI with CI for the purpose of finding cervical esophageal HGM. Using NBI endoscopy, there was an increase in the detection of the cervical esophageal HGM, especially in the detection of small-sized lesions. Our results suggest that NBI is useful for evaluating cervical esophageal HGM and improving the detection of small lesions. We also demonstrated that patients with cervical esophageal HGM have a predisposition for throat symptoms. Moreover, reflux esophagitis was present more frequently in patients with cervical esophageal HGM.

Conventional endoscopic studies reveal a prevalence of 1%-10%[1-7], but this frequency tends to be clinically underestimated. The latter is due to the predominant localization in the region upon or immediately distal to the upper esophageal sphincter. The upper esophagus is the most neglected area in a routine EGD. This region is quickly passed, extending the endoscope over the sphincter’s resistance; only by gently withdrawing the instrument can an HGM patch be detected. In this study, we demonstrated that the detection rate of cervical esophageal HGM could be improved from 4.7% to 8.3% with the help of NBI contrast. NBI should be considered as the standard illumination for the upper esophagus.

The aberrant gastric mucosa that forms the cervical esophageal HGM appears to have an embryological derivation. During development, the region destined to be the stomach descends from the region where the lung bud has begun to develop. With this, the columnar epithelial lining of the embryo’s esophagus undergoes several epithelization changes, which begin in the middle esophagus and progress in both directions. Cervical esophageal HGM is generally regarded as a congenital condition that results from an incomplete squamous epithelization, and the persisting columnar-lined mucosa differentiates into cervical HGM[18,19].

The largest autopsy series to date revealed that cervical esophageal HGM prevalence was 7.8% in 1000 autopsies of children[20]. Another necropsy study reported that the cervical esophageal HGM prevalence detected by the naked eye was 10% in 300 children[21]. These autopsy data were consistent with the highest values in reports from the endoscopic series[2,14]. In our study, the prevalence of cervical esophageal HGM, 8.3% in the NBI group, was also close to that of the autopsy series. The agreement between the endoscopically observed prevalence in adults and the postmortem prevalence of grossly detected lesions in children indicates that the cervical esophageal HGM most likely maintains itself throughout life, without regression or replacement by more typical esophageal lining.

The size of cervical esophageal HGM varies from 1 mm × 2 mm to 30 mm × 40 mm[1-7]. They can be unique or multiple and are capable of extending circumferentially. Circumferential cervical HGM is rare and usually manifests as dysphagia[22]. In our study, the size of the cervical esophageal HGM varied between 2 mm and 30 mm. The smallest observed cervical esophageal HGM sizes were classified as small, medium, and large in 40, 43 and 15 patients, respectively (Table 3). The NBI mode detected significantly more small-sized HGM lesions than the CI mode. The detected number of cervical HGMs varied according to different studies. According to our findings, 71 patients had single lesions; 19 had two patches; and 8 had three or more HGMs.

Microscopically, most cervical esophageal HGM is of the fundic-type gastric mucosa and contains both parietal and chief cells. Less frequently, cervical HGM is of the antral-type mucosa[1,2,5,8,23,24]. Repeated contractions of the sphincter make biopsying this area very difficult. In our study, biopsy was possible in 56 patients; fundic-type mucosa was found in 37 patients (66%) and antral-type mucosa in 19 patients.

Areas of intestinal metaplasia have been reported to occur within the cervical HGM[3,7,8,25]. The cervical HGM is generally regarded as a benign lesion with stable clinical and histopathological presentation during follow up[26]. However, malignant progression has been reported[27,28]. There have been 43 cases of adenocarcinoma in association with cervical esophageal HGM reported in the literature to date[19]. In our report, intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia was not observed in any of these cases. This lack of intestinal metaplasia was consistent with other reports[1,4-6,23]. Endoscopic surveillance is suggested for cases with intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia[19]. However, the best follow-up strategy for cases without such changes remains controversial.

In contrast to cervical esophageal HGM, Barrett’s esophagus is generally accepted as an acquired metaplastic change due to chronic GERD and is thought of as a premalignant lesion. Repeated attempts have been undertaken to identify an association between Barrett’s esophagus and cervical HGM, but the results have been conflicting. Based on their findings in a large case control study, Avidan et al[3] reported that the coincidence of the cervical HGM and Barrett’s esophagus could suggest a shared embryonic etiology. The link between these two entities was further supported by other studies[6,7,29]. Malhi-Chowla et al[30] reported that, based on their research in selected patients with high-grade dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus or adenocarcinoma, patients with cervical HGM might be at a higher risk for developing malignant Barrett’s esophagus and might share similar pathogenetic mechanisms. Nevertheless, other studies disagreed with the proposed association[1,4,5,23-25]. Distinct embryonic origins of HGM and Barrett’s esophagus were revealed by an immunohistochemical study. Feurle et al[31] demonstrated that the cervical esophageal HGM originates from embryonic gastric mucosa but that Barrett’s esophagus is derived from a very immature multipotent GI stem cell. Our findings also suggested no significant association between the two.

However, erosive esophagitis has been reported to be associated with cervical esophageal HGM[3,5,6,14,29]. In our study, we demonstrated that patients with cervical esophageal HGM were more likely to have erosive esophagitis than controls. This discrepancy in the association of Barrett’s esophagus and erosive esophagitis with cervical esophageal HGM is poorly understood.

Some investigators have identified cervical esophageal HGM as a risk factor for throat and upper esophageal symptoms[5,8,14], while others have denied such an association[1,4,9]. In this study, we found that throat symptoms were observed significantly more frequently in those patients with cervical esophageal HGM than in those who lacked cervical esophageal HGM (20.2% vs 7.4%; P < 0.0001). Gastric parietal cells of the large cervical HGM have been proven to be able to secrete a pathophysiologically effective amount of acid[1,5,32]. Moreover, Korkut et al[33] demonstrated that acid-independent episodes could be produced from small cervical HGM (sizes as small as 1-5 mm). The clinical symptoms of cervical HGM may be acid-related, and thus, a larger patch is theoretically more likely to cause symptoms. However, in our multiple logistic regression analysis, neither an increased number of patches nor a larger size of the patches was associated with the development of clinical symptoms in patients with HGM.

Symptomatic HGM type II patients require medical therapy as their primary mode of treatment. Complete symptom resolution has been reported by means of complete acid suppression with proton pump inhibition[32]. Alternatively, endoscopic ablation therapy with argon plasma coagulation has been shown to alleviate a chronic globus sensation in the patients with cervical HGM in two small prospective studies[34,35].

Acid production in the cervical esophageal HGM can induce chronic inflammation and ulceration. The subsequent healing process can lead to the formation of esophageal strictures. One of our patients was classified as HGM type III and suffered from acid-related peptic stenosis and dysphagia. Dysphagia and stenosis can be treated with proton pump inhibitors and/or endoscopic dilatation[22,32]. Our patient was treated with a proton pump inhibitor alone with good clinical response.

Cervical esophageal HGM has been shown to be colonized with H. pylori only when the bacteria were also present in the stomach[4,6,7,9,23]. Consistent with previous studies, our research revealed H. pylori colonization in 3 patients with HGM who also had H. pylori-positive gastritis. Gutierrez et al[25] reported that the H. pylori colonization of the cervical HGM was common and closely related to the H. pylori density in the stomach. Alagozlu et al[7] found that all patients who had active H. pylori infections in the cervical esophageal HGM suffered a globus sensation and speculated that H. pylori infection related to chronic inflammation may be responsible for their clinical symptoms. Whether H. pylori eradication therapy will improve clinical symptoms, as well as the nature of its long-term impacts on cervical HGM, remain subjects for further research.

There are several limitations in this study. There may be a detection bias because the endoscopist was not blind to the clinical symptoms, and it is possible that patients with dysphagia and throat symptoms were more carefully observed. A second issue is acid measurement. Because our study design did not include routine ambulatory dual-electrode pH monitoring, we were unable to determine how our observations would be affected by this factor. Larger cervical esophageal HGM patches theoretically produce more acid, but the threshold of patch size and the capacity of acid production to induce clinical symptoms were not determined. Thus, further evaluation of HGM’s acid production may contribute to a richer knowledge of this entity.

In summary, this study has several significant implications for the understanding of cervical esophageal HGM. It highlights the diagnostic yield of NBI illumination, which should be considered as the endoscopic diagnosis of choice for these lesions. This study also provided clinicopathological data indicating that most cervical esophageal HGM have fundic-type gastric mucosa and that 22% of patients could be symptomatic. Additional studies are needed to evaluate the acid production within the lesions and the longitudinal outcomes of patients with cervical esophageal HGM.

We thank Chih-Cheng Hsieh, MD, from the Taipei Veteran General Hospital for his contributions to ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring study.

Heterotopic gastric mucosa (HGM) in the cervical esophagus is a pink lesion of congenital origin characterized by the presence of gastric epithelium in the upper esophagus, although the clinical significance of such lesions remains unclear. Conventional endoscopic studies reveal a prevalence of 1%-10%, but this frequency tends to be underestimated because the lesion is located in the region upon or immediately distal to the upper esophageal sphincter.

The clinical significance of cervical esophageal HGM is closely related to its endoscopic detection rate. Apart from the increased awareness of the presence of such lesions by the examiner, a better diagnostic endoscopic tool should increase the diagnostic yield of HGM.

Narrow-band imaging (NBI) is an innovative optical technique that better contrasts the capillary pattern of the superficial layer than conventional imaging does. In this study, the authors demonstrated that the detection rate of the cervical esophageal HGM could be improved from 4.7% to 8.3% with the help of NBI contrast. Microscopically, mostly HGM is of the fundic-type gastric mucosa, containing both parietal and chief cells. Their data also showed that patients with HGM have a predisposition for throat symptoms that are often associated with reflux esophagitis.

NBI illumination should be considered the endoscopic diagnosis of choice for cervical esophageal HGM. In patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms or dysphagia, HGM should be evaluated.

This is a well-designed and well-presented paper in which the authors provide data as to the clinical usefulness of NBI endoscopy over conventional imaging in the identification of cervical esophageal HGM.

P- Reviewers: Abdel-Salam OME, Bugaj AM, Slomiany BL S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Jabbari M, Goresky CA, Lough J, Yaffe C, Daly D, Côté C. The inlet patch: heterotopic gastric mucosa in the upper esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:352-356. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Borhan-Manesh F, Farnum JB. Incidence of heterotopic gastric mucosa in the upper oesophagus. Gut. 1991;32:968-972. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 92] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Avidan B, Sonnenberg A, Chejfec G, Schnell TG, Sontag SJ. Is there a link between cervical inlet patch and Barrett’s esophagus? Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:717-721. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 60] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Akbayir N, Alkim C, Erdem L, Sökmen HM, Sungun A, Başak T, Turgut S, Mungan Z. Heterotopic gastric mucosa in the cervical esophagus (inlet patch): endoscopic prevalence, histological and clinical characteristics. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:891-896. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 61] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Baudet JS, Alarcón-Fernández O, Sánchez Del Río A, Aguirre-Jaime A, León-Gómez N. Heterotopic gastric mucosa: a significant clinical entity. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1398-1404. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yüksel I, Usküdar O, Köklü S, Başar O, Gültuna S, Unverdi S, Oztürk ZA, Sengül D, Arikök AT, Yüksel O. Inlet patch: associations with endoscopic findings in the upper gastrointestinal system. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:910-914. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Alagozlu H, Simsek Z, Unal S, Cindoruk M, Dumlu S, Dursun A. Is there an association between Helicobacter pylori in the inlet patch and globus sensation? World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:42-47. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Macha S, Reddy S, Rabah R, Thomas R, Tolia V. Inlet patch: heterotopic gastric mucosa--another contributor to supraesophageal symptoms? J Pediatr. 2005;147:379-382. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Maconi G, Pace F, Vago L, Carsana L, Bargiggia S, Bianchi Porro G. Prevalence and clinical features of heterotopic gastric mucosa in the upper oesophagus (inlet patch). Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:745-749. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Gono K, Obi T, Yamaguchi M, Ohyama N, Machida H, Sano Y, Yoshida S, Hamamoto Y, Endo T. Appearance of enhanced tissue features in narrow-band endoscopic imaging. J Biomed Opt. 2004;9:568-577. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 634] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 588] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Muto M, Katada C, Sano Y, Yoshida S. Narrow band imaging: a new diagnostic approach to visualize angiogenesis in superficial neoplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:S16-S20. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Su MY, Hsu CM, Ho YP, Chen PC, Lin CJ, Chiu CT. Comparative study of conventional colonoscopy, chromoendoscopy, and narrow-band imaging systems in differential diagnosis of neoplastic and nonneoplastic colonic polyps. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2711-2716. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 183] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lee YC, Lin JT, Chiu HM, Liao WC, Chen CC, Tu CH, Tai CM, Chiang TH, Chiu YH, Wu MS. Intraobserver and interobserver consistency for grading esophagitis with narrow-band imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:230-236. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 66] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hori K, Kim Y, Sakurai J, Watari J, Tomita T, Oshima T, Kondo C, Matsumoto T, Miwa H. Non-erosive reflux disease rather than cervical inlet patch involves globus. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1138-1145. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-120; quiz 1943. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, Johnson F, Hongo M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172-180. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1518] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1578] [Article Influence: 63.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | von Rahden BH, Stein HJ, Becker K, Liebermann-Meffert D, Siewert JR. Heterotopic gastric mucosa of the esophagus: literature-review and proposal of a clinicopathologic classification. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:543-551. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 125] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liebermann-Meffert D, Duranceau A, Setin HJ. Anatomy and embryology. The Esophagus, Vol I. Zuidema GD, Yeo ChJ. Shackelford’s surgery of the alimentary tract. 5th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders 2002; 3-39. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Chong VH. Clinical significance of heterotopic gastric mucosal patch of the proximal esophagus. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:331-338. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rector LE, Connerley ML. Aberrant mucosa in the esophagus in infants and in children. Arch Pathol. 1941;31:285-294. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Variend S, Howat AJ. Upper oesophageal gastric heterotopia: a prospective necropsy study in children. J Clin Pathol. 1988;41:742-745. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rogart JN, Siddiqui UD. Inlet patch presenting with food impaction caused by peptic stricture. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:e35-e36. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tang P, McKinley MJ, Sporrer M, Kahn E. Inlet patch: prevalence, histologic type, and association with esophagitis, Barrett esophagus, and antritis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:444-447. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Van Asche C, Rahm AE, Goldner F, Crumbaker D. Columnar mucosa in the proximal esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:324-326. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Gutierrez O, Akamatsu T, Cardona H, Graham DY, El-Zimaity HM. Helicobacter pylori and hetertopic gastric mucosa in the upper esophagus (the inlet patch). Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1266-1270. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Latos W, Sieroń-Stołtny K, Kawczyk-Krupka A, Operchalski T, Cieślar G, Kwiatek S, Bugaj AM, Sieroń A. Clinical evaluation of twenty cases of heterotopic gastric mucosa of upper esophagus during five-year observation, using gastroscopy in combination with histopathological and microbiological analysis of biopsies. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 2013;17:171-175. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Klaase JM, Lemaire LC, Rauws EA, Offerhaus GJ, van Lanschot JJ. Heterotopic gastric mucosa of the cervical esophagus: a case of high-grade dysplasia treated with argon plasma coagulation and a case of adenocarcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:101-104. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yoshida T, Shimizu Y, Kato M. Image of the month. Use of magnifying endoscopy to identify early esophageal adenocarcinoma in ectopic gastric mucosa of the cervical esophagus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:e91-e93. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Rosztóczy A, Izbéki F, Németh IB, Dulic S, Vadászi K, Róka R, Gecse K, Gyökeres T, Lázár G, Tiszlavicz L. Detailed esophageal function and morphological analysis shows high prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s esophagus in patients with cervical inlet patch. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25:498-504. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Malhi-Chowla N, Ringley RK, Wolfsen HC. Gastric metaplasia of the proximal esophagus associated with esophageal adenocarcinoma and Barrett’s esophagus: what is the connection? Inlet patch revisited. Dig Dis. 2000;18:183-185. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Feurle GE, Helmstaedter V, Buehring A, Bettendorf U, Eckardt VF. Distinct immunohistochemical findings in columnar epithelium of esophageal inlet patch and of Barrett's esophagus. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:86-92. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Galan AR, Katzka DA, Castell DO. Acid secretion from an esophageal inlet patch demonstrated by ambulatory pH monitoring. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1574-1576. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 62] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Korkut E, Bektaş M, Alkan M, Ustün Y, Meco C, Ozden A, Soykan I. Esophageal motility and 24-h pH profiles of patients with heterotopic gastric mucosa in the cervical esophagus. Eur J Intern Med. 2010;21:21-24. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Meining A, Bajbouj M, Preeg M, Reichenberger J, Kassem AM, Huber W, Brockmeyer SJ, Hannig C, Höfler H, Prinz C. Argon plasma ablation of gastric inlet patches in the cervical esophagus may alleviate globus sensation: a pilot trial. Endoscopy. 2006;38:566-570. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 51] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Bajbouj M, Becker V, Eckel F, Miehlke S, Pech O, Prinz C, Schmid RM, Meining A. Argon plasma coagulation of cervical heterotopic gastric mucosa as an alternative treatment for globus sensations. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:440-444. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 72] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |