Published online Dec 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i46.8703

Revised: September 27, 2013

Accepted: October 19, 2013

Published online: December 14, 2013

Processing time: 189 Days and 18.6 Hours

AIM: To clarify the short and long-term results and to prove the usefulness of endoscopic resection in type 3 gastric neuroendocrine tumors (NETs).

METHODS: Of the 119 type 3 gastric NETs diagnosed from January 1996 to September 2011, 50 patients treated with endoscopic resection were enrolled in this study. For endoscopic resection, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) was used. Therapeutic efficacy, complications, and follow-up results were evaluated retrospectively.

RESULTS: EMR was performed in 41 cases and ESD in 9 cases. Pathologically complete resection was performed in 40 cases (80.0%) and incomplete resection specimens were observed in 10 cases (7 vs 3 patients in the EMR vs ESD group, P = 0.249). Upon analysis of the incomplete resection group, lateral or vertical margin invasion was found in six cases (14.6%) in the EMR group and in one case in the ESD group (11.1%). Lymphovascular invasions were observed in two cases (22.2%) in the ESD group and in one case (2.4%) in the EMR group (P = 0.080). During the follow-up period (43.73; 13-60 mo), there was no evidence of tumor recurrence in either the pathologically complete resection group or the incomplete resection group. No recurrence was reported during follow-up. In addition, no mortality was reported in either the complete resection group or the incomplete resection group for the duration of the follow-up period.

CONCLUSION: Less than 2 cm sized confined submucosal layer type 3 gastric NET with no evidence of lymphovascular invasion, endoscopic treatment could be considered at initial treatment.

Core tip: Endoscopic treatment was suitable for tumors measuring approximately 20 mm or smaller in size, with no lymph node or distant metastasis and limited to the submucosal layer of type 3 gastric neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), similar to endoscopic treatment guidelines applied to other gastrointestinal NETs.

- Citation: Kwon YH, Jeon SW, Kim GH, Kim JI, Chung IK, Jee SR, Kim HU, Seo GS, Baik GH, Choi KD, Moon JS. Long-term follow up of endoscopic resection for type 3 gastric NET. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(46): 8703-8708

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i46/8703.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i46.8703

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are slow-growing malignancies with distinct biological and clinical characteristics. Although these tumors have long been a source of clinical and pathologic interest, their fundamental biology still eludes precise delineation[1]. Despite the relative rarity of gastric NETs, their diagnosis is increasing due to the recent widespread use of diagnostic endoscopy[2-4]. Yearly age-adjusted incidence is approximately 0.2 per population of 100000.

Enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells, the main endocrine cell types in type 1 and type 2 gastric NETs, are highly susceptible to gastrin trophic stimuli. Under circumstances that cause hypergastrinemia, such as chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG) in pernicious anemia (type 1) or gastrin-producing neoplasms in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES)/multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) 1 (type 2), multiple ECL cell carcinoids occur in the oxyntic corpus and fundus mucosa of the stomach[5,6]. Type 1 and 2 gastric NETs are usually considered benign, with a low risk of malignancy. However, type 3 gastric NETs are composed of different endocrine cells, which grow sporadically, irrespective of gastrin, in an otherwise normal mucosa. Most of these tumors show lymphoinvasion, angioinvasion, and deep wall invasion at the time of diagnosis, and they often present with metastases, which are found in 50%-70% of well-differentiated, and in up to 100% of poorly differentiated tumors[6-9]. As a worse overall mortality of type 3 gastric NETs, aggressive surgery is considered the initial therapeutic approach, generally. Many reports on the efficacy of endoscopic treatment for gastric NETs have been published[10-13]. However, few studies have reported on endoscopic treatment of type 3 gastric NETs.

In this study, we will conduct a retrospective review of the outcomes and long-term prognosis of endoscopic treatment on type 3 gastric NETs. In addition, we demonstrate the efficacy of endoscopic treatment on type 3 gastric NETs.

This work has been carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) of the World Medical Association. This study was approved ethically by University Hospital Kyungpook Trust (KNUMC_ 12-1005). All patients provided informed written consent for this study.

After receiving appropriate Institutional Review Board approval, members of the Korean college of Helicobacter and Upper Gastrointestinal Research retrospectively enrolled patients who were diagnosed with histologically proven gastric NETs from 10 hospitals between January 1996 and September 2011. Based on endoscopic findings, all gastric NETs were classified according to the Paris endoscopic classification[14]. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans were available for diagnosis of lymph node involvement or other organ metastasis. These patients were then analyzed with respect to their presenting signs and symptoms, associated disease, tumor characteristics (number, size, site, and the presence of metastasis), and outcome. From the 225 gastric NETs, we reviewed patients’ plasma gastrin levels and other associated diseases, such as ZES and multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 1, to diagnose type 3 gastric NETs. The exact criteria used to decide between endoscopic or surgical treatment was dependent on the tumor size, tumor shape (combined ulceration or depressed lesions), or evidence of adjacent lymph node metastasis.

Resection specimens processed by formalin fixation were serially sectioned at 2 mm intervals, and tumor involvement to the lateral and vertical margins was assessed. In addition, histopathological type, tumor size, depth of invasion, and lymphovascular invasion were evaluated microscopically. Pathologically complete resection was defined according to the following findings: (1) en bloc resection; (2) the tumor was a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor (classical-type carcinoid) according to World Health Organization (WHO) classification[15]; (3) tumor invasion was limited to the submucosal layer; (4) no lateral and vertical margin involvement; and (5) no lymphovascular invasion.

We evaluated tumor characteristics, such as the measured size, number, and location of tumors. Tumor size was estimated using biopsy forceps (FB 21K-1; Olympus Medical Systems Co, Tokyo, Japan), which was approximately 6 mm in length when opened. Tumor location was reported according to the longitudinal axis (fundus, cardia, body, or antrum). All lesions were imaged with adjacent anatomical structures to ensure that the exact location of the tumor was recorded and proved histologically by endoscopic biopsy. Endoscopic ultrasonography was used for measuring the depth of invasion of gastric NETs. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) was performed after obtaining informed consent. Submucosal injection of saline mixed with epinephrine was performed to elevate tumor tissues from the underlying muscularis propria. Next, EMR, using a hood and snare, or submucosal dissection was applied for removal of the lesion.

The follow-up program consisted of endoscopic examinations at three, six, and twelve-month intervals, and CT scans and blood tests were performed at 12-month intervals. Follow-up endoscopy was performed depending on the follow-up program, and for histological examinations of NETs recurrence, biopsies were performed at iatrogenic ulcer scar lesions that had undergone endoscopic treatment. CT examination findings were normal in all patients at the end of follow up.

All continuous variable data are presented as the mean ± SE. Statistical significance was calculated using unpaired Student’s t test. To assess the difference between two procedures, univariate analysis was performed using Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was set at 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., United States).

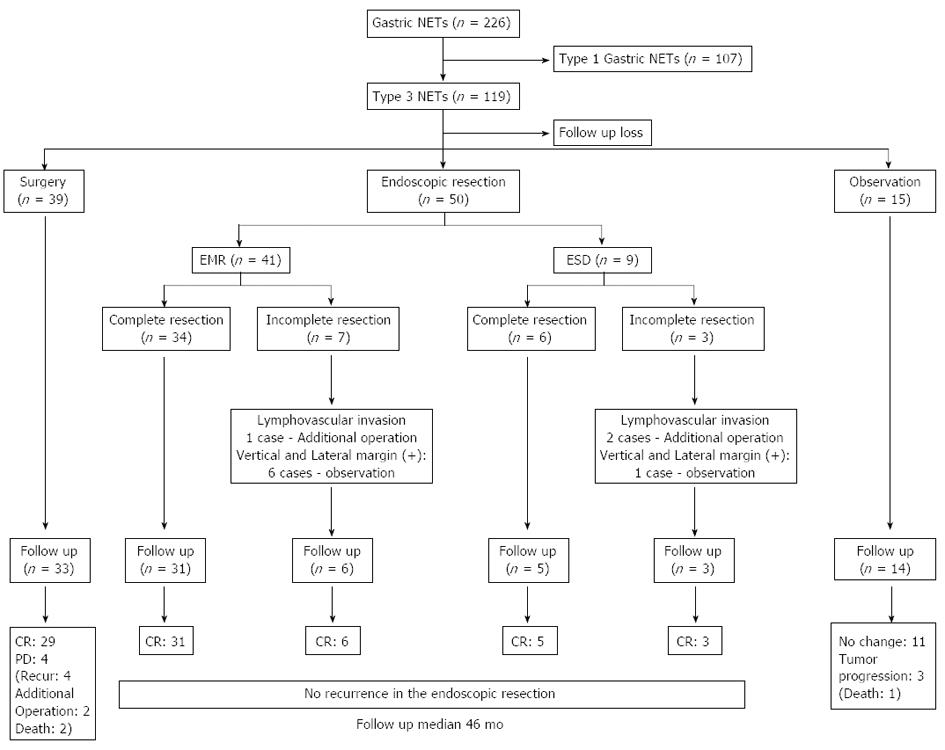

Overall, in the 226 cases of gastric NETs, 119 cases (52.4%) were diagnosed as type 3 gastric NETs. Of the 119 patients, 50 patients (42.0%) received endoscopic interventions for the treatment of type 3 gastric NET lesions (Figure 1). The average age of the patients was 58.6 (25-85) years. Twenty-eight (56.0%) patients were male and 22 (44.0%) patients were female. Asymptomatic patients were the most common, and abdominal discomfort was the second most common presenting symptom (28.0%) in patients who had type 3 gastric NETs. Upon analysis of the associated underlying disease, five patients (10.0%) had diabetes mellitus (DM), one patient (2.0%) had thyroid disease and early gastric cancer (EGC), and two patients (4.0%) had other combined malignancies (Table 1).

| Male:female | 28:22 |

| Mean age, yr | 58.6 ± 12.2 |

| Associated symptoms | |

| Abdominal discomfort | 14 (28.0) |

| Body weight loss | 1 (2.0) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (2.0) |

| Other symptom | 1 (2.0) |

| Associated disease | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (10.0) |

| Thyroid disease | 1 (2.0) |

| Combined other malignancy | 2 (4.0) |

| Number of tumors | |

| 1 | 48 (96.0) |

| ≥ 2 | 2 (4.0) |

| Tumor location | |

| Antrum | 4 (8.0) |

| Body | 38 (76.0) |

| Fundus or cardia | 8 (16.0) |

| Tumor size | |

| ≤ 10 mm | 33 (66.0) |

| > 10 mm | 17 (34.0) |

| EUS invasion depth | |

| Mucosa and submucosa | 49 (98.0) |

| MP | 1 (2.0) |

| Treatment methods | |

| EMR | 41 (82.0) |

| ESD | 9 (18.0) |

Based on the endoscopic findings, superficial elevated type (type IIa) and solitary lesions (96%) were most prevalent. Upon analysis of the location of the type 3 gastric NETs, 38 lesions (76.0%) were found on the body. Based on the EUS evaluation, there were 49 cases (98.0%) of confined tumors in the mucosal or submucosal layer, and one tumor (2.0%) was suspicious of invasion into the muscular propria (MP) layer. No lymphatic invasion or other organ metastasis findings was observed in the imaging stud (Table 1).

Of the 50 patients who had been treated with endoscopic intervention, 41 patients (82.0%) were treated by EMR and 9 patients (18.0%) were treated by ESD. The mean tumor size of the gastric NETs was 10.2 ± 6.3 mm, and compared with the mean tumor size, no significant difference was observed between the two groups (9.3 mm vs 14.2 mm in the EMR vs ESD group, P = 0.055). All tumors were determined as pathologically well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. Upon analysis of the resected specimens, 11 tumors and six tumors in the EMR and ESD groups, respectively, were gastric NETs measuring 10 mm or more in size (P = 0.031); pathologically complete resections were achieved in 40 cases (80.0%), and incomplete resection specimens were seen in 10 cases (7 vs 3 patients in the EMR vs ESD group, P = 0.249). Lateral or vertical margin invasion was found in six cases (14.6%) in the EMR group and in one case in the ESD group (11.1%). Lymphovascular invasions were observed in two cases (22.2%) in the ESD group and in one case (2.4%) in the EMR group (P = 0.080) (Table 2).

| EMR(n = 41) | ESD(n = 9) | P value | |

| Mean resection size (range, mm) | 9.3 ± 5.6 | 14.2 ± 7.8 | 0.055 |

| Tumor size > 10 mm | 11 (26.8) | 6 (66.7) | 0.031 |

| Pathologically complete resection | 35 (85.4) | 6 (66.7) | 0.249 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 1 (2.4) | 2 (22.2) | 0.080 |

| Additional operation | 1 (2.4) | 2 (22.2) | 0.080 |

The mean tumor size of a complete resection was 9.6 (2-32) mm, and the size for an incomplete resection was 12.4 (3-20) mm (P = 0.011). The mean tumor size of lymphovascular invasion cases was larger than that of the no lymphovascular invasion group, however, there was no significant difference (P = 0.416) (Table 3). All cases of with a lymphovascular invasion tumor underwent an additional operation, while other incomplete resection cases were followed up by observation (Figure 1). There were no complications after the endoscopic treatment procedures.

| Tumor size | P value | |

| Complete resection (range, mm) | ||

| Yes (n = 40) | 9.6 ± 6.3 | 0.011 |

| No ( = 10) | 12.4 ± 6.1 | |

| Lymphovascular invasion (range, mm) | ||

| Yes (n = 3) | 16.3 ± 4.2 | 0.416 |

| No (n = 47) | 9.8 ± 6.2 |

Of the 50 patients who underwent endoscopic treatment, five patients (10.0%) were lost to follow-up, and 45 patients (90%) were included in the follow-up. The median follow-up duration was 46 (13-60) mo. No evidence of tumor recurrence was found upon endoscopic and histological examinations in both groups. There was also no evidence of recurrence during follow-up imaging studies. In addition, no mortality was reported in either the complete resection group or the incomplete resection group during the follow-up duration. If 5 years was used as a cut-off point, 20 patients showed a disease-free state during this period.

Carcinoids were first described by Oberndorfer in 1907 to describe a group of tumors of the gastrointestinal tract that had a relatively indolent course and were considered to be intermediate between adenomas and carcinomas in terms of malignancy potential. Currently, these tumors are also known by the modern term of gastric NETs, which include a subset of tumors demonstrating features of neuroendocrine differentiation[15]. Surgery has been the most common treatment of gastric NETs; however, these tumors often receive suboptimal management, and some patients still undergo inappropriate surgery. As the diagnosis of gastric NETs is increasing with the widespread use of screening diagnostic endoscopy, treatment using the endoscopic method is becoming a matter of concern. In type 1 gastric NETs, endoscopic polypectomy or endoscopic mucosal resection is small (< 1 cm) and few (< 3-5 cm) in number[16] because the clinical behavior of these tumors is usually indolent. Most are grade 1 tumors with TNM stage I disease and no mortality during prolonged follow-up[17]. Type 3 gastric NETs represent 15%-25% of NETs and are not related to hypergastrinemia and ECL hyperplasia. The lesions are typically solitary, larger than 1-2 cm, ulcerated, and deeply invasive. The lesions are usually located in the gastric fundus and body, but may also occur in the antrum; they are also more frequent in males[6,18-20] and are characterized by a far more aggressive course. Type 3 gastric NETs present with lymph node and distant metastases in more than 50% of cases. Therefore, partial or total gastrectomy with local lymph node resection is considered an acceptable treatment[21,22] in the absence of visceral metastases. Additionally, systemic chemotherapy is also considered appropriate if surgery is not feasible, even if, thus far, the results are not very encouraging[23]. Only small (< 10 mm), well differentiated (G1) type 3 gastric NETs may be treated non-operatively by endoscopic resection. Because of the generally favorable tumor biology, surgery and/or local ablation should be considered even in metastatic gastric NETs[3]. Recently, Saund et al[24] reported that tumor size and depth can predict lymph node metastasis for gastric NETs and that endoscopic resection may be appropriate for intraepithelial (IE) tumors <2 cm and perhaps tumors < 1 cm invading into the lamina propria or submucosa. In our present study, complete pathological resections were achieved in 80.4% of patients (85.4% in the EMR group vs 66.7% in the ESD group). Better results for the pathological complete resection rate for treatment have usually been reported with the ESD technique. However, in the current study, the EMR group showed a more preferable complete resection rate compared with the ESD group. We presumed that tumor size is a contributing factor. Based on analysis of resected tumor size, the mean tumor size of the ESD group was larger than that of the EMR group (P = 0.055), and the pathologically complete resection ratio showed no significant difference in both modality groups (P = 0.249). Even in cases with tumor sizes greater than 10 mm (14 cases), which were confined to the submucosal layer and no lymphovascular invasion, endoscopic treatment showed no recurrence during the follow-up duration. Considering these factors, the ESD technique was useful for large type 3 gastric NETs. The long-term results of the endoscopic treatment only group (n = 43) showed no recurrence or mortality. Therefore, we could conclude that endoscopic treatment was suitable for tumors measuring approximately 20 mm or smaller in size, with no lymph node or distant metastasis and limited to the submucosal layer of type 3 gastric NETs, similar to endoscopic treatment guidelines applied to other gastrointestinal NETs.

Our study has some limitations. First, this study is a retrospective analysis of clinical records. However, the data are believed to be reliable because all patients with type 3 gastric NETs treated using the endoscopic method at 10 institutions between January 1996 and September 2011 were included. The second limitation is that this study has a possible selection bias because it was not randomized. However, we consider the selection bias to be minimal because the patient characteristics and the median tumor sizes of patients with type 3 gastric NETs were not different. Third, the outcome of the endoscopic resection and selection of methods for endoscopic resection were different for each institution. However, each operator had sufficient skill to perform the endoscopic procedure, and the modality of endoscopic treatment was generally accepted for the treatment of gastric NETs. The final limitation is that we enrolled patients according to the WHO 2000 system for NET classification, due to retrospective study design. Therefore, we could not evaluate tumor histology on the basis of proliferative activity (Ki-67 index, mitotic rate) in which gastric NETs are graded as G1, G2, or G3.

In a conclusion, if the tumor is confined in the submucosal layer, there is no evidence of lymphovascular invasion, and the tumor size is smaller than 2 cm, endoscopic treatment could be applied for the initial treatment of type 3 gastric NETs.

Lots of controversies still exist about the optimal treatment of gastric neuroendocrine tumors (NETs). Type 3 gastric NETs are known as more aggressive disease course compared with type 1 gastric NETs. So, management of type 3 gastric NETs are comparable to that used for gastric adenocarcinomas, which includes partial or total gastrectomy with extended lymph node resection. However, in the case of small sized tumor, endoscopic resection is applied for initial treatment, nowadays.

To evaluate of the long-term results and to prove the usefulness of endoscopic resection in type 3 gastric NETs.

Endoscopic treatment was suitable for tumors measuring approximately 20 mm or smaller in size, with no lymph node or distant metastasis and limited to the submucosal layer of type 3 gastric NETs.

This present study suggest that the tumor size, the depth of invasion and evidence of lymphovascular invasion must be considered before performing endoscopic treatment for type 3 gastric NETs.

This study described the efficacy of endoscopic resection for the type 3 gastric NETs which size is less than 2 cm, confined submucosal layer, and no evidence of lymphovascular invasion.

P- Reviewers: Bloomston M, Jensen RT, Ke YQ, Ooi LL S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:934-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1848] [Cited by in RCA: 1848] [Article Influence: 84.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 50-year analysis of 562 gastric carcinoids: small tumor or larger problem? Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:23-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Scherübl H, Cadiot G, Jensen RT, Rösch T, Stölzel U, Klöppel G. Neuroendocrine tumors of the stomach (gastric carcinoids) are on the rise: small tumors, small problems? Endoscopy. 2010;42:664-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ellis L, Shale MJ, Coleman MP. Carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract: trends in incidence in England since 1971. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2563-2569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ruszniewski P, Delle Fave G, Cadiot G, Komminoth P, Chung D, Kos-Kudla B, Kianmanesh R, Hochhauser D, Arnold R, Ahlman H. Well-differentiated gastric tumors/carcinomas. Neuroendocrinology. 2006;84:158-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Burkitt MD, Pritchard DM. Review article: Pathogenesis and management of gastric carcinoid tumours. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1305-1320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rindi G, Azzoni C, La Rosa S, Klersy C, Paolotti D, Rappel S, Stolte M, Capella C, Bordi C, Solcia E. ECL cell tumor and poorly differentiated endocrine carcinoma of the stomach: prognostic evaluation by pathological analysis. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:532-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Delle Fave G, Capurso G, Annibale B, Panzuto F. Gastric neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2004;80 Suppl 1:16-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Schindl M, Kaserer K, Niederle B. Treatment of gastric neuroendocrine tumors: the necessity of a type-adapted treatment. Arch Surg. 2001;136:49-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hopper AD, Bourke MJ, Hourigan LF, Tran K, Moss A, Swan MP. En-bloc resection of multiple type 1 gastric carcinoid tumors by endoscopic multi-band mucosectomy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1516-1521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hosokawa O, Kaizaki Y, Hattori M, Douden K, Hayashi H, Morishita M, Ohta K. Long-term follow up of patients with multiple gastric carcinoids associated with type A gastritis. Gastric Cancer. 2005;8:42-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Borch K, Renvall H, Kullman E, Wilander E. Gastric carcinoid associated with the syndrome of hypergastrinemic atrophic gastritis. A prospective analysis of 11 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11:435-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sjöblom SM, Sipponen P, Järvinen H. Gastroscopic follow up of pernicious anaemia patients. Gut. 1993;34:28-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Endoscopic Classification Review Group. Update on the paris classification of superficial neoplastic lesions in the digestive tract. Endoscopy. 2005;37:570-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 559] [Cited by in RCA: 636] [Article Influence: 31.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Solcia E, Klöppel G, Sobin LH, Williams E. Histological typing of endocrine tumours. New York: Springer 2000; . |

| 16. | Ichikawa J, Tanabe S, Koizumi W, Kida Y, Imaizumi H, Kida M, Saigenji K, Mitomi H. Endoscopic mucosal resection in the management of gastric carcinoid tumors. Endoscopy. 2003;35:203-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Thomas D, Tsolakis AV, Grozinsky-Glasberg S, Fraenkel M, Alexandraki K, Sougioultzis S, Gross DJ, Kaltsas G. Long-term follow-up of a large series of patients with type 1 gastric carcinoid tumors: data from a multicenter study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;168:185-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Calender A. Molecular genetics of neuroendocrine tumors. Digestion. 2000;62 Suppl 1:3-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Borch K, Ahrén B, Ahlman H, Falkmer S, Granérus G, Grimelius L. Gastric carcinoids: biologic behavior and prognosis after differentiated treatment in relation to type. Ann Surg. 2005;242:64-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dakin GF, Warner RR, Pomp A, Salky B, Inabnet WB. Presentation, treatment, and outcome of type 1 gastric carcinoid tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:368-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gilligan CJ, Lawton GP, Tang LH, West AB, Modlin IM. Gastric carcinoid tumors: the biology and therapy of an enigmatic and controversial lesion. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:338-352. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Plöckinger U, Rindi G, Arnold R, Eriksson B, Krenning EP, de Herder WW, Goede A, Caplin M, Oberg K, Reubi JC. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of neuroendocrine gastrointestinal tumours. A consensus statement on behalf of the European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society (ENETS). Neuroendocrinology. 2004;80:394-424. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Massironi S, Sciola V, Spampatti MP, Peracchi M, Conte D. Gastric carcinoids: between underestimation and overtreatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2177-2183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Saund MS, Al Natour RH, Sharma AM, Huang Q, Boosalis VA, Gold JS. Tumor size and depth predict rate of lymph node metastasis and utilization of lymph node sampling in surgically managed gastric carcinoids. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2826-2832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |