INTRODUCTION

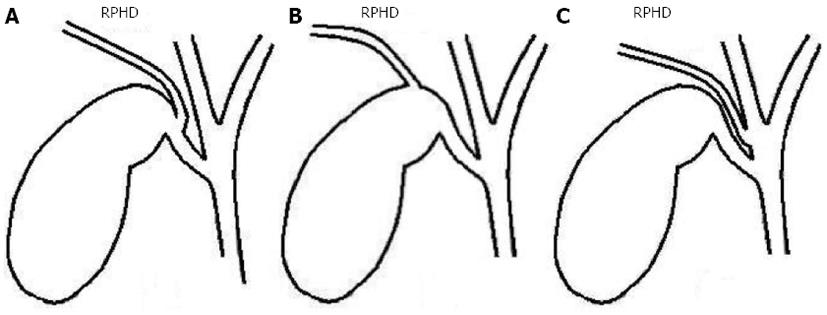

Bile duct injury (BDI) is one of the most serious complications of both open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. They often result from misidentification of anatomy by the operating surgeons and anatomic variations within the biliary tree[1]. Variations in biliary tree anatomy occur in about 25% of patients with aberrant right hepatic ducts being the most common. The low insertion of a right sectoral hepatic duct into the common hepatic duct or the cystic duct (Figure 1) increases the risk of injury during both open[2,3] and laparoscopic cholecystectomy[4,5]. Therefore, a detailed knowledge and awareness of all possible anatomical variants is crucial for surgeons to avoid complications.

Figure 1 Dangerous anatomical variants of right posterior hepatic duct draining into the cystic duct (A), gall bladder neck (B) or the common hepatic duct (C).

RPHD: Right posterior hepatic duct.

Herein we describe the diagnosis and treatment of an isolated right posterior sectoral BDI sustained during laparoscopic cholecystectomy in two patients. We emphasize the preventive measures to be taken at surgery and discuss the diagnostic and therapeutic options.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

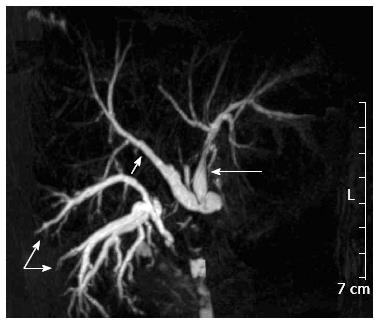

A 15-year-old female patient with a symptomatic gallstone disease underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy converted to an open procedure in November 2010 in a regional institution. The patient was discharged home on the 6th day post operation. She presented 5 d following discharge with abdominal pain and was found to have a subhepatic fluid collection on ultrasound scanning. At relaparotomy drainage of a biloma and abdominal lavage was performed. The patient was discharged home again 16 d following cholecystectomy with an abdominal drain left in place as it still produced around 150-200 mL of bile daily. Due to persistence of a biliary leak, endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) was performed 20 d after initial surgery. This showed no evidence of a leak and a consult of a hepatobiliary surgeon was requested. During careful evaluation of all the ERC images it became obvious that the right posterior (segments 6 and 7) sectoral bile duct was clearly missing (Figure 2). The diagnosis of an isolated Strasberg type C bile duct injury[6] was further confirmed by magnetic resonance cholangiography with maximum-intensity-projection using the slice-stacking technique and T2-weighted sequences. This showed a leak from the right posterior sectoral duct that was isolated from the remaining biliary system (Figure 3). Continued external drainage for a period of several weeks was recommended allowing time for the local inflammation to settle and for possible spontaneous closure of the leak or to serve as a bridge for a definitive repair. The leak persisted at around 150-250 mL/d at which stage definitive surgery was opted for. A Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy to the damaged posterior sectoral duct was initially planned. However, an attempt to identify the damaged duct during surgery was unsuccessful. Therefore, a bisegmental (segments 6 and 7) hepatic resection was performed in order to remove the affected parenchyma of the liver. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged home 10 d after surgery. She remains well at present at 27 mo post cholecystectomy and 24 mo after definitive surgical treatment.

Figure 2 Endoscopic retrograde cholangiogram showing seemingly “normal” biliary tree with no evidence of a biliary leak.

However, only the left hepatic duct (long arrow) and the right anterior hepatic duct (short arrow) are visible.

Figure 3 Magnetic resonance cholangiography with the use of T2-weighted sequences and maximum-intensity-projection imaging.

The fluid-containing bile ducts as high signal-intensity structures; the right posterior hepatic ducts of segments 6 and 7 are shown (double arrow) with no connection to the right anterior duct (single short arrow) and the left hepatic duct (single long arrow); the abdominal drain placed in the subhepatic area and draining the bile externally is also visible in between the right anterior and posterior hepatic ducts.

Case 2

A 21-year-old female patient underwent cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis in a regional hospital in September 2012. The procedure started laparoscopically but was converted to open surgery because of difficulties localizing anatomical structures. The patient was discharged 6 d following surgery. She was readmitted one week later with fever, abdominal pain and vomiting. Abdominal ultrasound confirmed a subhepatic fluid collection, which proved to be bilious in origin at percutaneous drainage. A drain was left in the subhepatic space and the biliary leak continued (200-300 mL/d) despite its absence on ERC performed. At this stage, 56 d post cholecystectomy, the patient was referred to the authors institute for further management. Following admission the patient was found to be in reasonably good health other than for the persistent biliary leak. A magnetic resonance cholangiogram was performed and this revealed a leak from a right posterior sectoral duct that had no communication with the remaining biliary tree (Strasberg type C injury)[6]. The ERC was performed once again and confirmed an intact intra and extrahepatic biliary tree with an absent right posterior duct. The patient was then offered surgical repair. During surgery, an open stump of the right posterior sectoral duct (confirmed by intraoperative cholangiography) measuring around 3 mm in diameter was identified. A Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy was performed. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged home 11 d after surgery. She remains well and asymptomatic at 4 mo of follow-up with undilated biliary tree on ultrasonography and normal values of serum bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase and transaminase levels.

DISCUSSION

Dangerous anatomy, pathology and surgery are three main risk factors which may be responsible for BDI during open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy[7]. Incorrect interpretation of anatomy appears to be the most common cause of injury, particularly in isolated right sectoral BDI[4,5]. The most dangerous scenario includes the cystic duct located close to or joining the sectoral duct or the sectoral duct draining into the cystic duct or the gallbladder neck (Figure 1)[7,8]. This should be always kept in mind during surgery and anticipated until proven otherwise. In order to prevent the injury and identify any variant anatomy early, complete circumferential dissection of the gall bladder neck and the cystic duct should be performed before clip placement.

Anomalous drainage of the right posterior sectoral bile duct into the cystic duct or the common hepatic duct is seen in around 2%-5% of patients[4,5,9-11]. Its injury does not belong to the original classification of BDI described by Bismuth et al[12]. It is recognized though by Strasberg classification as the occlusion (type B) or a leak (type C) from a duct not in communication with the common bile duct[6]. The true incidence of Strasberg type B injury may be underestimated since some of them are likely to be asymptomatic and pass unnoticed leading to atrophy or segmental cirrhosis of part of the liver. While occlusion of the duct usually leads to cholestasis or recurrent episodes of cholangitis[3,13], its transection presents mainly with signs of biliary peritonitis or external biliary leak via the abdominal drain[4,14-16], which was the case in our patients.

Proper diagnosis and management of right sectoral BDI remains difficult. The results of ERC may be interpreted as “normal” with no biliary leaks visible (Figure 2). The leak may then be erroneously attributed to injury to a minor biliary radical in the gall bladder fossa (the ducts of Luschka) and delay the diagnosis. However, careful evaluation of the obtained ERC images may reveal that only the right anterior sector of the liver (segments 5 and 8) is visualized and the posterior (segments 6 and 7) missing[3,4] (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance cholangiography can further confirm the lack of communication between the injured duct and the common bile duct (Figure 3). This makes endoscopic treatment impossible in such cases and is essential for treatment planning.

The treatment depends on the timing of recognition of the type of injury. External biliary drainage should allow prompt control of the leak, eliminate the risk of sepsis and serve as a bridge for definitive repair[4]. Total nonoperative management has recently been advocated as a way to obviate the need for surgery in up to 50% of patients[16]. If the leak persists beyond approximately 8 wk, treatment with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy is usually indicated[12,16,17]. However, the risk of late stricture at the anastomosis may be as high as 33%[4] making the resection of the affected liver sector an attractive alternative[4,18]. As we were not able to find and locate the injured duct during surgery in the first case, this was the only treatment option for our patient. Placement of a percutaneous, transhepatic catheter into the injured duct prior to surgery may help the surgeon identify the site of injury facilitating dissection of the hepatic hilum prior to reconstruction[4]. However, application of this technique on an undilated biliary system may be a challenge even for an experienced hepatobiliary radiologist[16]. For this reason we did not decide to attempt this approach in our patient. While surgery remains the mainstay treatment in most centers, management of such injuries using the interventional radiology approach has also been reported. This includes the application of minimally invasive and percutaneous techniques of ablation of the affected duct by ethanol or acetic acid injection[19,20].

In summary, proper diagnosis and management of right sectoral BDI remains difficult. It should always be suspected and looked for if a biliary leak following cholecystectomy persists despite its absence on endoscopic cholangiogram. In addition to a bilioenteric reconstruction with the Roux limb of jejunum, resection of the affected part of the liver is another treatment option.