Published online Sep 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5763

Revised: July 24, 2013

Accepted: August 5, 2013

Published online: September 14, 2013

Processing time: 92 Days and 16.2 Hours

Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) is defined as hepatic venous outflow obstruction at any level from the small hepatic veins to the junction of the inferior vena cava (IVC) and the right atrium, regardless of the cause of obstruction. We present two cases of acute iatrogenic BCS and our clinical management of these cases. The first case was a 43-year-old woman who developed acute BCS following the implantation of an IVC stent for the correction of stenosis in the IVC after hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis. The second case was a 61-year-old woman with complete obstruction of the outflow of hepatic veins during bilateral hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis. Acute iatrogenic BCS should be considered a rare complication following hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis. Awareness of potential hepatic outflow obstructions and timely management are critical to avoid poor outcomes when performing hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis.

Core tip: The occurrence of acute iatrogenic Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) following hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis is rarely reported. However, it may occur following a particularly difficult hepatectomy for complicated hepatolithiasis. Here, we report two cases of acute BCS and present our clinical experience in managing these cases.

- Citation: Bai XL, Chen YW, Zhang Q, Ye LY, Xu YL, Wang L, Cao CH, Gao SL, Khoodoruth MAS, Ramjaun BZ, Dong AQ, Liang TB. Acute iatrogenic Budd-Chiari syndrome following hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis: A report of two cases. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(34): 5763-5768

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i34/5763.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5763

Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) is characterized by hepatic venous outflow obstruction at the level of the hepatic venules, the large hepatic veins (HV), the inferior vena cava (IVC), or the right atrium[1]. Obstruction of the hepatic venous outflow tract, which leads to hepatic congestion as blood flows into, but not out of the liver, results in damage to the hepatic parenchymal cells and the cells lining the hepatic sinusoids. BCS can cause liver dysfunction and even lead to liver failure.

There are multiple known causes of BCS, including both heritable and acquired hypercoagulable states, compression or invasion of the IVC, as well as other less common miscellaneous causes[2-4]. BCS can also be idiopathic. Here, we report two cases of acute BCS with an uncommon cause and present our clinical experience in managing these cases.

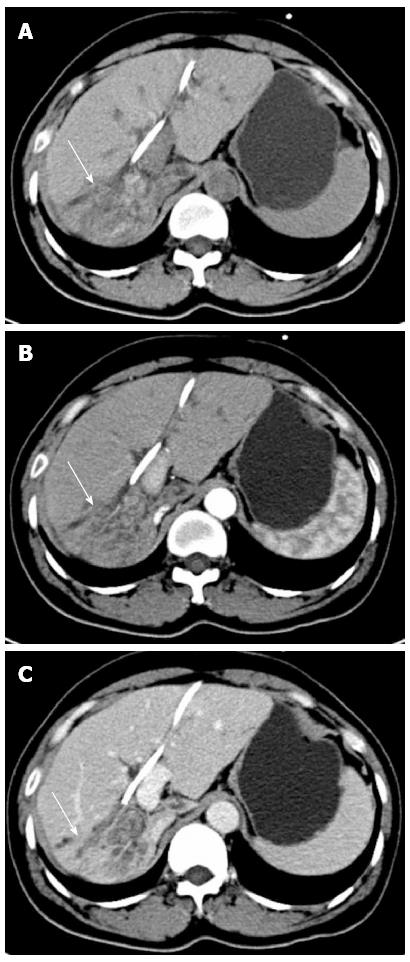

A 43-year-old woman developed acute BCS following the implantation of an IVC stent for correction of stenosis in the IVC after hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis. The patient was admitted with recurrent cholangitis. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showed lithiasis in the intra- and extra-hepatic bile duct, dilatation of the biliary tract and enlargement of the gallbladder. In addition, computed tomography (CT) (Figure 1) demonstrated right lobe, caudate lobe and segment II (Counauid’s classification) atrophy of the liver. After biliary decompression by endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography and control of infection, the following procedures were performed: right hemi-hepatectomy, segment II resection, caudate lobectomy, cholecystectomy, choledochotomy, and choledochojejunostomy. During right hepatectomy, the IVC was accidentally wedge resected due to the obscure boundary between the IVC and the right lobe of the liver, which was immediately sutured.

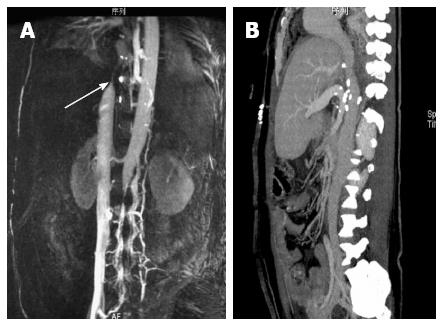

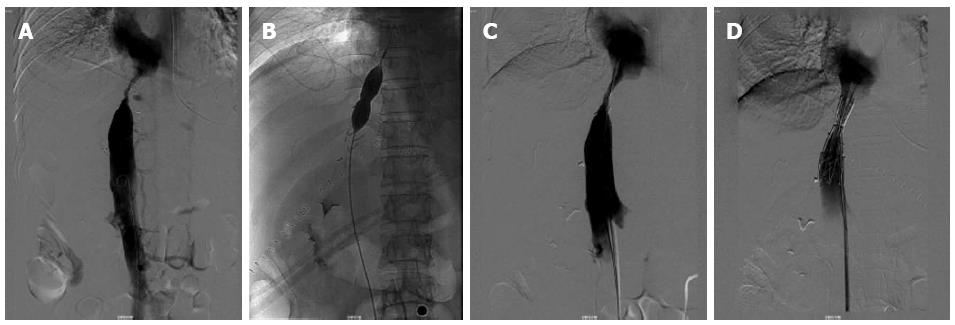

After surgery, the patient developed congestive hepatopathy, manifested as rapidly progressive abdominal distention, and severe pitting edema of the lower back and lower limbs. Magnetic resonance venography 3 d after operation (Figure 2) showed obvious stenosis near the entrance of the three HVs into the IVC, at the same location where the wedge was resected and repaired. Emergent balloon dilation was performed using a balloon catheter and a metallic stent (30 mm × 75 mm), guided by digital subtraction angiography (Figure 3). However, after this procedure, the patient’s liver function deteriorated (Table 1). Contrast enhanced CT confirmed hepatic congestion and revealed that the proximal end of the stent was directly at the entrance of the HV into the IVC. Doppler ultrasonography showed reduced blood flow velocity in the HVs, the maximum velocity in the middle HV was 14 cm/s. There was turbulence in the left HV and backflow in the portal vein. Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with acute BCS, caused by the improper position of the stent which blocked the entrance of the HV into the IVC.

| Before hepatectomy | After hepatectomy | After metallic stent placement | 5 d after IVC patch repair | |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 26.7 | 45.2 | 83.3 | 26.3 |

| DBIL (μmol/L) | 13.6 | 34.3 | 45.6 | 17.3 |

| IBIL (μmol/L) | 13.1 | 15.8 | 37.7 | 9 |

| ALT (U/L) | 146 | 294 | 335 | 24 |

| AST (U/L) | 73 | 199 | 287 | 16 |

| WBC (106/L) | 4.0 | 10.3 | 5.9 | 6.0 |

| Hb (g/L) | 107 | 81 | 80 | 88 |

| PLT (106/L) | 117 | 51 | 57 | 73 |

| PT (s) | 11 | 18.4 | 20.5 | 16.0 |

| INR | 0.92 | 1.53 | 1.7 | 1.33 |

Following this diagnosis, the patient was immediately scheduled for surgery to remove the metallic stent. The stenosis of the IVC was 5 cm long and the diameter of the lumen was only 1 cm. The stenosis was repaired using a BalMedic (Beijing Balance Medical Co. Ltd, China) pericardial patch (2 cm × 5 cm) under cardiopulmonary bypass and deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (Figure 4). After surgery, the clinical manifestations of BCS were alleviated, liver function improved, and the patient recovered without further complications (Table 1). Anticoagulation therapy with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) for 3 d followed by Warfarin for 3 mo was administered. At one year follow-up, the patient had no recurrent cholangitis, no symptoms related to BCS, and normal liver function. CT angiography showed no obvious stenosis in the IVC (Figure 2).

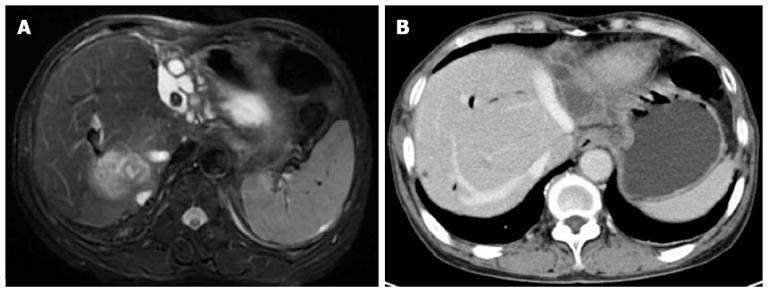

A 61-year-old woman experienced complete obstruction of the outflow of HVs during bilateral hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis. She underwent an open cholecystectomy and choledocholithotomy with T-tube drainage 15 years previously for cholelithiasis. In recent years, she suffered from recurrent cholangitis. Imaging findings (Figure 5) showed bilateral hepatolithiasis, dilation of the biliary tract, common bile duct stones, and a hypodense area on CT in the posterior lobe of the right liver, suggesting infection.

During surgery, the liver was found to be distorted with marked atrophy of the right posterior hepatic lobe and left half of the liver. In addition, the right anterior hepatic lobe (segment V and VIII), and the right caudate lobe showed significant hyperplasia. No neoplasms were found in the wall of the bile duct during choledochoscopy. The liver was then freed to begin resection of the left part of the liver, the right posterior lobe and the right caudate lobe. The left half was resected first. Then, the right HV was revealed and divided using a 45-mm endoscopic linear stapler (Echelon 45 ENDOPATH Stapler, Ethicon ENDO-Surgery, Cincinnati, Ohio, United States). Immediately after ligation, there was sudden and significant congestion of the liver, and hepatic outflow blockage was suspected. The liver was examined and stenosis was found in the middle HV, which was thought to be the left HV. Thus, we set out to repair the middle HV and the right HV.

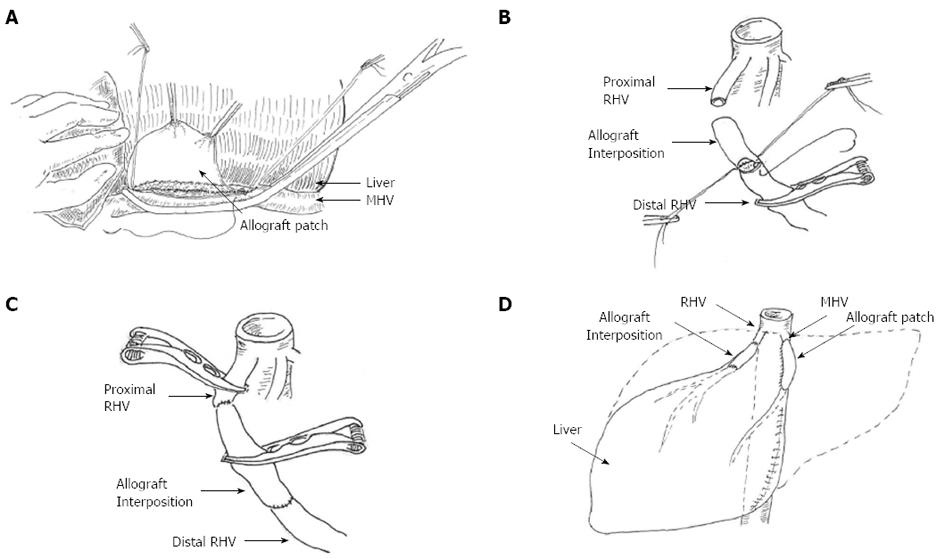

The stenosed middle HV was opened and cryopreserved (-80 °C). A common iliac artery allogenic graft about 3 cm was prepared. The lumen of the artery was opened and anastomosed to the MHV forming a patch to broaden the stenosed middle HV. Liver swelling was observed to subside after middle HV reconstruction. Both ends of the right HV were then clamped using vascular clamps to control bleeding, and a 1-2 cm allogeneic iliac vein graft was used to repair the right HV (Figure 6). The outflow of blood from the liver was then assessed; no thrombosis or air embolism was found and the liver swelling subsided. It should be noted that the hepatic blood inflow of the porta hepatis was blocked several times during this procedure. The longest blockage time was 40 min with a total length of 60 min. During the procedure, the liver was cold conditioned using ice to attenuate warm ischemic injury. A T-tube was placed in the common bile duct for drainage and to improve accessibility for the future removal of residual stones in the biliary tract. Due to the episode of HV obstruction, a right posterior lobectomy was not performed.

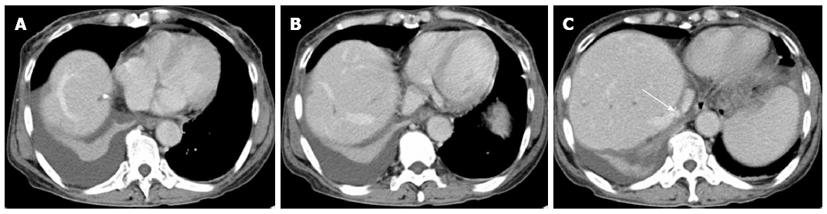

Postoperatively, peak liver enzymes aspartate aminotransferase 380 U/L and alanine aminotransferase 407 U/L were detected, with normal total bilirubin at postoperative day 2. Liver enzymes decreased to the normal range within one week. Postoperative recovery was uneventful. Anticoagulation therapy with LMWH for 3 d followed by Warfarin for 3 mo was administered. Postoperative CT scan (Figure 7) showed no obstruction or thrombosis in the right or middle HV.

BCS is a rare clinical condition characterized by hepatic venous outflow obstruction due to various causes[1]. The most common causes of BCS are hypercoagulable states, other uncommon causes have been identified such as tumor invasion, otherwise its origins are idiopathic[3]. There are also sporadic reports of BCS as a surgical complication after liver transplantation[5], and right hepatectomy resulting from torsion of the remnant liver[6]. In this study, we report two cases of acute BCS following hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis.

Hepatolithiasis is a common disease in Asian countries[7]. A multimodal approach has been advocated in the management of this condition, including endoscopic, percutaneous, or open surgery. Hepatectomy is considered the most effective treatment and is indicated in some cases, especially those with recurrent bacterial cholangitis and irreversible atrophy of parts of the liver[8-10]. Despite the efficacy of this approach, higher morbidity and mortality is associated with hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis[9]. As observed in the two reported cases, performing a partial hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis is a particularly difficult and challenging procedure because of the dense perihepatic adhesions (due to recurrent cholangitis or previous surgery), and abnormal intrahepatic anatomy (due to the atrophy-hypertrophy complex)[11]. These challenges require detailed preoperative evaluation to avoid venous injury, including high resolution imaging to identify the intrahepatic anatomy, as well as the relationship between the liver and the IVC. In addition, due to co-existing atrophy and regeneration of the liver, the function of the HV is frequently abnormal, thus it is crucial to ligate the major HV for testability before continuing with the procedure. Based on our experience with hepatic outflow obstruction, we believe that awareness of possible complications and timely management are critical for attenuating liver congestion and salvaging the liver.

The treatment of BCS is based on its cause, consisting of anticoagulation therapy, thrombolytic therapy, radiological procedures (i.e., angioplasty, stenting or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts), surgical decompression, surgical shunts, and surgical correction of the lesion. Rarely, liver transplantation may be necessary if the liver is irreparably damaged[12,13]. Of note, balloon angioplasty and stent placement has been increasingly favored and the effectiveness of these procedures has been documented[1,14]. However, in the first case presented above, the stenosis was very close to the secondary porta of the liver, and the placement of the stent was incorrect as it blocked the entrance of the HV into the IVC. Thus, based on our experience, surgical broadening of the stricture of the IVC is strongly advocated. With regard to our second case, it is evident that no other method is a substitute for surgical reconstruction of the HV to resolve hepatic congestion.

In conclusion, episodes of acute iatrogenic BCS following hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis are a rare occurrence. Awareness of potential hepatic outflow obstructions and timely management are critical to avoid poor outcomes when performing hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis. From our experience, prompt surgical reconstruction of the HV should be favored to salvage the congested liver.

P- Reviewers Pan GD, Mancuso A, Takagi H, Wang CC, Xu Z S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Janssen HL, Garcia-Pagan JC, Elias E, Mentha G, Hadengue A, Valla DC. Budd-Chiari syndrome: a review by an expert panel. J Hepatol. 2003;38:364-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 356] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Aydinli M, Bayraktar Y. Budd-Chiari syndrome: etiology, pathogenesis and diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2693-2696. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Menon KV, Shah V, Kamath PS. The Budd-Chiari syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:578-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Senzolo M, Cholongitas EC, Patch D, Burroughs AK. Update on the classification, assessment of prognosis and therapy of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2:182-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yamagiwa K, Yokoi H, Isaji S, Tabata M, Mizuno S, Hori T, Yamakado K, Uemoto S, Takeda K. Intrahepatic hepatic vein stenosis after living-related liver transplantation treated by insertion of an expandable metallic stent. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1006-1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang JK, Truty MJ, Donohue JH. Remnant torsion causing Budd-Chiari syndrome after right hepatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:910-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tsui WM, Lam PW, Lee WK, Chan YK. Primary hepatolithiasis, recurrent pyogenic cholangitis, and oriental cholangiohepatitis: a tale of 3 countries. Adv Anat Pathol. 2011;18:318-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dong J, Lau WY, Lu W, Zhang W, Wang J, Ji W. Caudate lobe-sparing subtotal hepatectomy for primary hepatolithiasis. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1423-1428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tabrizian P, Jibara G, Shrager B, Schwartz ME, Roayaie S. Hepatic resection for primary hepatolithiasis: a single-center Western experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:622-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yang T, Lau WY, Lai EC, Yang LQ, Zhang J, Yang GS, Lu JH, Wu MC. Hepatectomy for bilateral primary hepatolithiasis: a cohort study. Ann Surg. 2010;251:84-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Black DM, Behrns KE. A scientist revisits the atrophy-hypertrophy complex: hepatic apoptosis and regeneration. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2002;11:849-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hung WC, Fang CY, Wu CJ, Lo PH, Hung JS. Successful metallic stent placement for recurrent stenosis after balloon angioplasty of membranous obstruction of inferior vena cava. Jpn Heart J. 2001;42:519-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kohli V, Wadhawan M, Gupta S, Roy V. Posttransplant complex inferior venacava balloon dilatation after hepatic vein stenting. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33:205-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sharma S, Texeira A, Texeira P, Elias E, Wilde J, Olliff SP. Pharmacological thrombolysis in Budd Chiari syndrome: a single centre experience and review of the literature. J Hepatol. 2004;40:172-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |