Published online Jan 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i3.411

Revised: October 15, 2012

Accepted: November 11, 2012

Published online: January 21, 2013

Processing time: 130 Days and 5.1 Hours

Endoscopic epinephrine injection is relatively easy, quick and inexpensive. Furthermore, it has a low rate of complications, and it is widely used for the management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. There have been several case reports of gastric ischemia after endoscopic injection therapy. Inadvertent intra-arterial injection may result in either spasm or thrombosis, leading to subsequent tissue ischemia or necrosis, although the stomach has a rich vascular supply and the vascular reserve of the intramural anastomosis. In addition to endoscopic injection therapy, smoking, hypertension and atherosclerosis are risk factors of gastric ischemia. We report a case of gastric ischemia after submucosal epinephrine injection in a 51-year-old woman with hypertension and liver cirrhosis.

- Citation: Kim SY, Han SH, Kim KH, Kim SO, Han SY, Lee SW, Baek YH. Gastric ischemia after epinephrine injection in a patient with liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(3): 411-414

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i3/411.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i3.411

Acute gastric ischemia rarely occurs due to the rich vascular supply of the stomach and the vascular reserve of the intramural anastomosis[1]. Therefore, there have been few case reports of gastric ischemia worldwide[2,3]. In the rare cases that have been reported, the risk factors for gastric ischemia were smoking, hypertension, atherosclerosis and endoscopic injection therapy[3]. Endoscopic epinephrine injection is a widely used therapy for the management of nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding, and it promotes initial hemostasis to stop the bleeding[4].

We report a case of gastric ischemia and necrosis after endoscopic epinephrine injection at the site of the lesion of a biopsy in a patient with liver cirrhosis and hypertension

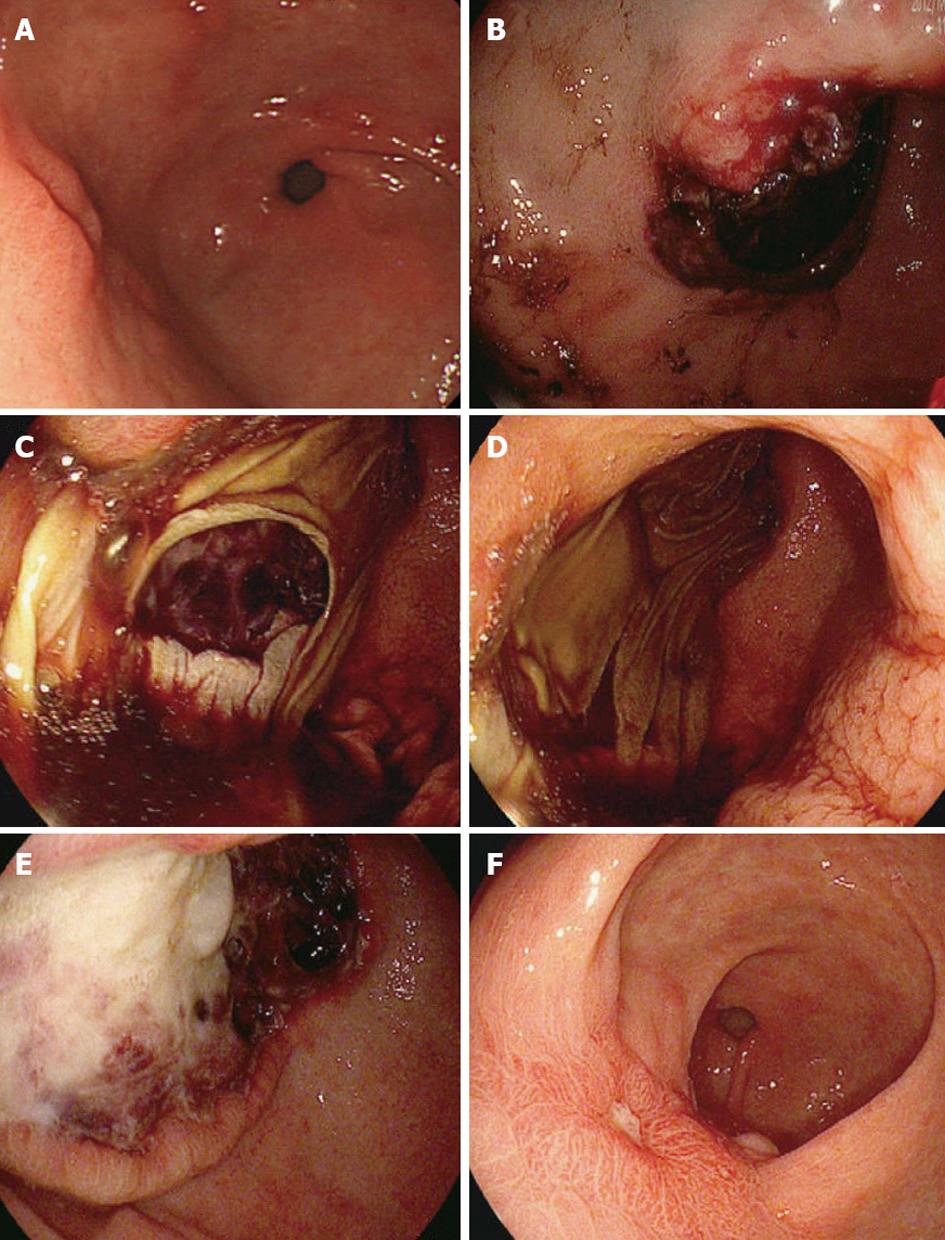

A 51-year-old woman with hypertension and liver cirrhosis was admitted with hematemesis and hematochezia. One day prior to admission, an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed, revealing an elevated lesion with a central depression of the gastric antrum. A variceal lesion was not observed. She underwent an endoscopic biopsy of the lesion of the antrum (Figure 1A), and submucosal injection was performed with a 1:10 000 solution of epinephrine due to bleeding after the endoscopic biopsy. Injection boluses of 2 mL were used for a total of 6 mL. The patient returned home safely after hemostasis. However, she presented to the emergency department reporting massive hematemesis and hematochezia the next day.

In the emergency room, she was in a severe distress with a heart rate of 90 beats/min, an arterial blood pressure of 100/70 mmHg and a respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min. Her abdomen was tender to palpation without guarding. A digital rectal examination was positive for bloody stools. The chest X-ray film and electrocardiogram were normal, as was the plain film of the abdomen. A complete blood count revealed anemia (hemoglobin level, 10.4 g/100 mL; hematocrit level, 29.7%) leukopenia (2360 cells/mm3 with 56.3% polymorphonuclear cells) and thrombocytopenia (53 000 cells/mm3). The Child-Pugh classification was A with a mildly prolonged prothrombin time of 14.4 s and hypoalbuminemia (3.0 g/dL). The upper endoscopy revealed oozing bleeding on the site of a previous biopsy, and the lesion was covered by a hemorrhagic clot (Figure 1B). We considered hemoclipping at first, but it was difficult to target the site of clipping because the hemorrhagic clot blocked our view, although vigorous irrigation and precise vessel exposure were not observed. Therefore, we again attempted hemostasis by submucosal injection of a 1:10 000 solution of epinephrine (a total dose of 8 mL). We were not concerned that epinephrine injection would result in gastric ischemia or necrosis at that time. Two days later, the patient presented with severe epigastric pain and melena. The hemoglobin level was 7.7 g/dL. An upper endoscopy was performed. The endoscopy revealed a mucosal dissection with extensive ulcerated and necrotic areas from the distal to the proximal antrum (Figure 1C and D). We believed that this condition represented mucosal necrosis and severe ischemia. Emergency abdominal computed tomography ruled out arterial thrombosis and perforation, and it revealed an edematous mural thickening with mild mucosal enhancement in the antrum of the stomach. We decided to use conservative treatment because the signs of perforation or sepsis were not observed and the patient had underlying liver cirrhosis. The patient was treated with proton pump inhibitor perfusion, wide spectrum antibiotics and parenteral nutrition. Three days later, endoscopy was performed again to identify changes in the lesion. Endoscopy showed a large extensive ulcer with fibrinous and hemorrhagic exudates surrounded by a clear elevated margin (Figure 1E). We thought that the ischemic ulcer was in a healing state, and conservative care was continued. Her condition was gradually improved, and there was no sign of bleeding. A liquid diet was started, and the patient was discharged from the hospital after 2 wk. A follow-up endoscopy 2 mo later showed the decreased size of the ulcer surrounded by regenerative epithelia with a clear margin (Figure 1F).

The rich blood supply of the stomach protects the stomach from ischemia and necrosis[1]. Acute gastric ischemia, an emergency condition associated with high mortality, is rare[3]. Possible risk factors of gastric ischemia include smoking, hypertensive and atherosclerotic vascular disease, trauma, infection, and epinephrine injection[3]. We performed epinephrine injection to control the bleeding after a biopsy. Most cases of post-biopsy bleeding stop on their own without endoscopic therapy. However, we performed the injection therapy because of underlying cirrhosis and the strength of the injection procedure. Injection of epinephrine is effective for controlling upper gastrointestinal bleeding[5]. This technique is relatively easy, quick, and inexpensive. The complication rate associated with epinephrine injection was minimal[2].

However, a few cases have been reported of ischemic necrosis of the stomach and/or duodenum after injection of epinephrine (with or without a sclerosant) to control ulcer bleeding[2,4]. There are multiple mechanisms of action invoked to explain the efficacy of epinephrine, including vasoconstriction, a vascular tamponade effect, and enhanced platelet aggregation[5]. We postulated that gastric ischemia in this case resulted from the injection of a 1:10 000 solution of epinephrine as a vasoconstrictive drug. First, the epinephrine injection might have caused vascular contraction and opening of the intramural arteriovenous shunts, which could have contributed to gastric ischemia. Second, direct mechanical distress of the gastric artery caused by the needle followed by immediate obliteration of the arterial lumen was most likely the cause of the ischemia. The double injection of epinephrine most likely aggravated the gastric ischemia in this patient. Furthermore, morphological alterations in the gastric microcirculation in cirrhosis might be the cause of ischemia. One study reported that increased arteriovenous anastomoses in the gastric wall were related to the occurrence of acute gastric mucosal lesions in patients with liver cirrhosis[6]. Another study showed arteriovenous anastomoses of 50% in the gastric wall and a straight pattern of the arterioles with dilation of the precapillaries, capillaries, and submucosal and subserosal veins in cirrhotic patients, although the sample size was small[7]. In addition, the long-term history of hypertension, might have caused atherosclerotic vascular changes. Therefore, the abnormal mucosal structure resulting from liver cirrhosis and hypertension was an important risk factor, in addition to the injection of epinephrine, for gastric ischemia in this patient.

Clinically, gastric infarction presents as an acute abdominal emergency with diarrhea or hematemesis that rapidly progresses to acute peritonitis, irreversible septic shock, and death if untreated[8]. The treatment of acute necrotizing ischemic gastritis is emergency laparotomy with resection when necessary. In most cases, gastric ischemic necrosis has been treated with surgery[3,4,9]. In our case, the patient was only treated with conservative therapy with total parenteral nutrition, intravenous antibiotics, and a proton pump inhibitor. The results of this conservative treatment were favorable.

This is first report of the occurrence of gastric ischemia after epinephrine injection in a patient with liver cirrhosis. We report a case of fatal gastric ischemia and postulate that accidental intra-arterial injection may be responsible for this event. Inadvertent intra-arterial injection may result in either spasm or thrombosis and lead to subsequent tissue ischemia or necrosis, and underlying liver cirrhosis might influence this rare complication. Therefore, we should pay more attention to the risk of bleeding in underlying vascular disease or cirrhosis during endoscopic hemostasis.

P- Reviewers Atta HM, De Gottardi A S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Jacobson ED. The circulation of the stomach. Gastroenterology. 1965;48:85-109. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Lee TH, Lee JS, Cho KH, Kim SH, Kim JO, Cho JY, Shim CS. A case of ischemic gastric necrosis after submucosal epinephrine injection. Korean J Med. 2009;77:488-492. |

| 3. | Richieri JP, Pol B, Payan MJ. Acute necrotizing ischemic gastritis: clinical, endoscopic and histopathologic aspects. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:210-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hilzenrat N, Lamoureux E, Alpert L. Gastric ischemia after epinephrine injection for upper GI bleeding in a patient with unsuspected amyloidosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:307-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Park WG, Yeh RW, Triadafilopoulos G. Injection therapies for nonvariceal bleeding disorders of the GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:343-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hasumi A, Aoki H, Shimazu M, Kawata S, Yoshimatsu Y. Causative relationship between a hyperdynamic state due to increased A-V anastomoses in the gastric wall and AGML in patients with liver cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1989;4 Suppl 1:143-145. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Hashizume M, Tanaka K, Inokuchi K. Morphology of gastric microcirculation in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1983;3:1008-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cohen EB. Infarction of the stomach; report of three cases of total gastric infarction and one case of partial infarction. Am J Med. 1951;11:645-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dorta G, Michetti P, Burckhardt P, Gillet M. Acute ischemia followed by hemorrhagic gastric necrosis after injection sclerotherapy for ulcer. Endoscopy. 1996;28:532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |