Published online Mar 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i12.2000

Revised: January 5, 2013

Accepted: January 18, 2013

Published online: March 28, 2013

Processing time: 112 Days and 18.5 Hours

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a pathogen and the most frequent cause of gastric ulcers. There is also a close correlation between the prevalence of H. pylori infection and the incidence of gastric cancer. We present the case of a 38-year-old woman referred by her primary care physician for screening positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT), which showed a nodular strong accumulation point with standardized uptake value 5.6 in the gastric fundus. Gastroscopy was then performed, and a single arched ulcer, 12 mm in size, was found in the gastric fundus. Histopathological examination of the lesion revealed chronic mucosal inflammation with acute inflammation and H. pylori infection. There was an obvious mitotic phase with widespread lymphoma. Formal anti-H. pylori treatment was carried out. One month later, a gastroscopy showed a single arched ulcer, measuring 10 mm in size in the gastric fundus. Histopathological examination revealed chronic mucosal inflammation with acute inflammation and a very small amount of H. pylori infection. The mitotic phase was 4/10 high power field, with some heterotypes and an obvious nucleolus. Follow-up gastroscopy 2 mo later showed the gastric ulcer in stage S2. The mucosal swelling had markedly improved. The patient remained asymptomatic, and a follow-up PET-CT was performed 6 mo later. The nodular strong accumulation point had disappeared. Follow-up gastroscopy showed no evidence of malignant cancer. H. pylori-associated severe inflammation can lead to neoplastic changes in histiocytes. This underscores the importance of eradicating H. pylori, especially in those with mucosal lesions, and ensuring proper follow-up to prevent or even reverse early gastric cancer.

-

Citation: Li TT, Qiu F, Wang ZQ, Sun L, Wan J. Rare case of

Helicobacter pylori -related gastric ulcer: Malignancy or pseudomorphism? World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(12): 2000-2004 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i12/2000.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i12.2000

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a Gram-negative microaerophilic bacterium that colonizes the stomach of approximately two-thirds of the human population and is involved in the pathogenesis of various gastroenterological diseases including gastric ulcer and gastric cancer. H. pylori’s interaction with the host has an impact on the severity of these diseases and their clinical outcome[1,2].

The mechanisms of H. pylori-related colonization are not fully understood. However, different types of H. pylori virulence factors, especially cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA), vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA), outer inflammation protein A and so on are reported to be correlated with H. pylori-related diseases. One of the major bacterial virulence factors, the VacA, seems to be involved in the physiologic mechanism. The VacA protein encoded by the polymorphic H. pylori VacA gene, is produced and secreted by all bacterium strains and induces the formation of intracellular vacuoles in epithelial cell lines in vitro. Environmental and demographic data also interfere with the pathophysiology of H. pylori-associated gastric diseases[3].

We present a case of a 38-year-old woman with a history of thyroid cancer who was referred by her primary care physician for a screening positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT). She was essentially asymptomatic and did not report any abdominal pain, dysphagia, nausea, or vomiting. Findings of a physical examination were unremarkable.

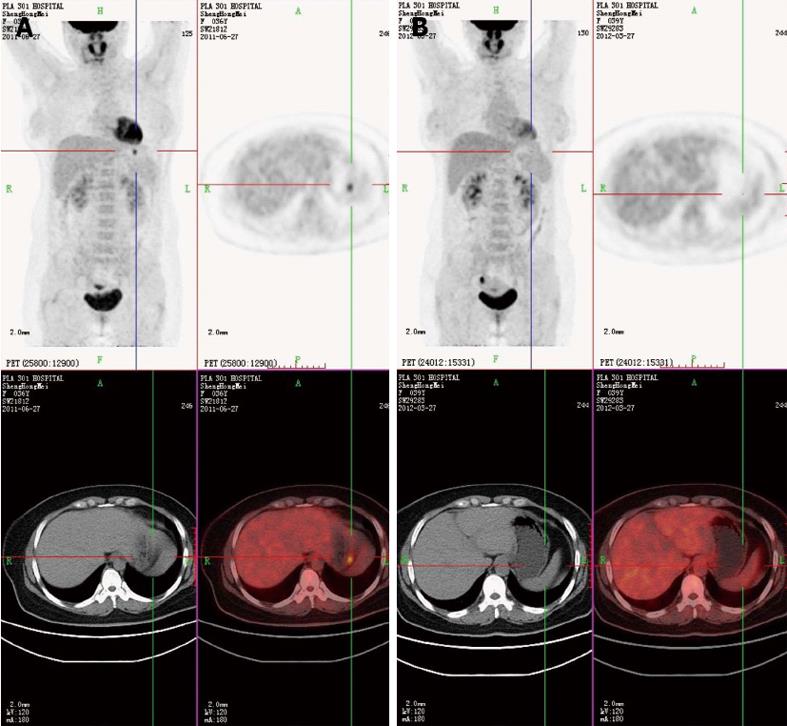

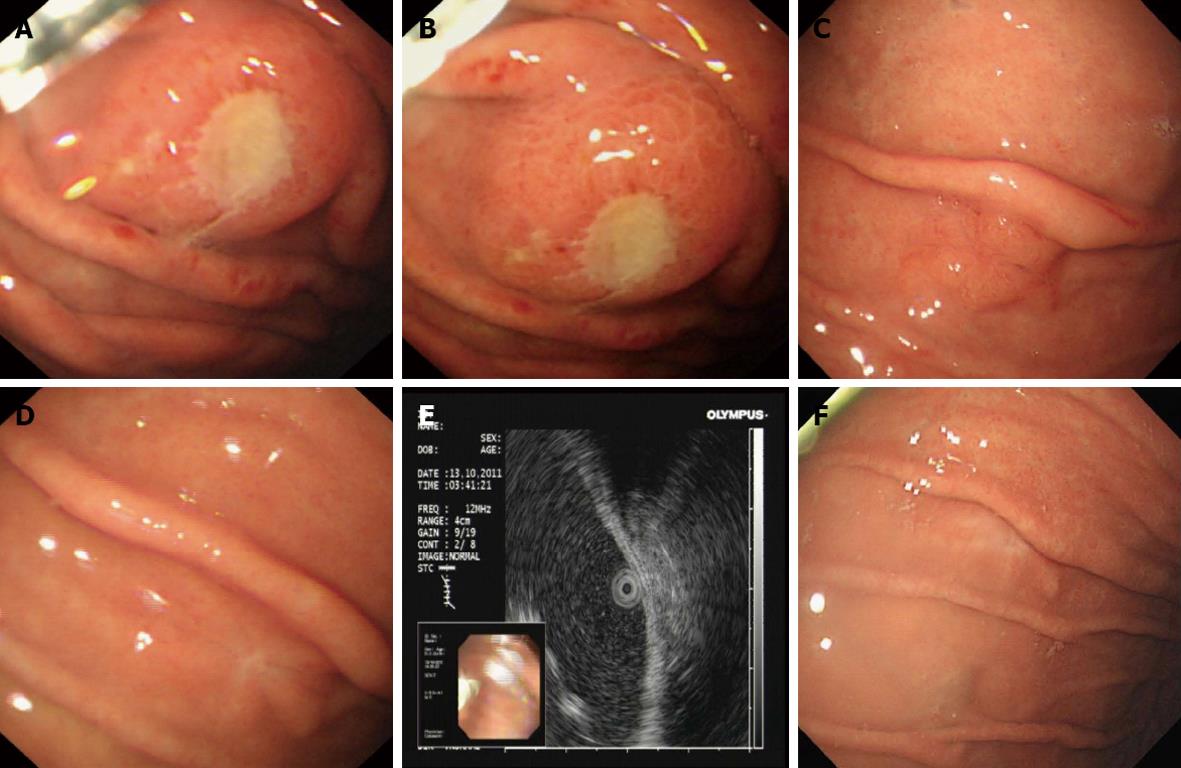

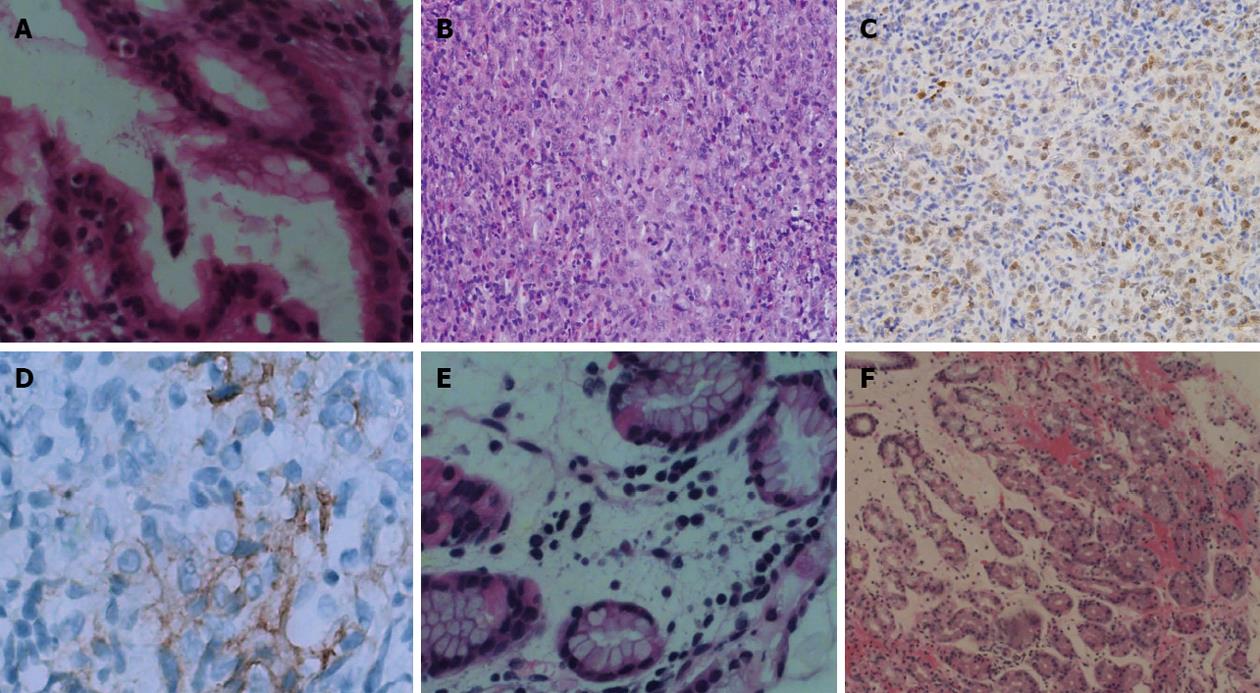

PET-CT showed a nodular strong accumulation point with standardized uptake value (SUV) 5.6 in the gastric fundus (Figure 1A). Gastroscopy was then performed, and demonstrated a single arched ulcer, measuring 12 mm in size, in the gastric fundus (Figure 2A and B). Histopathological examination revealed that the lesion had chronic mucosal inflammation with acute inflammation and H. pylori infection. There was an obvious mitotic phase with widespread lymphoma immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD4 (T cell), CD3 (T cell), CD20, Ki-67 (+25%), CD79a (+++), PAX-5, CD45RO and negative for CD56, TIA-1, TIF-1, Bcl-6, CD10, CD30, CD34, CD117, CK, MUM-1, MPO (Figure 3A).

The patient was given H. pylori eradication therapy, based on proton pump inhibitor-clarithromycin-amoxicillin-mucosal protective agent treatment, the so-called quadruple 14 d therapy. One month later, gastroscopy was performed and showed a single arched ulcer, measuring 10 mm in size in the gastric fundus (Figure 2C). Histopathological examination revealed that the lesion had chronic mucosal inflammation with acute inflammation and a small amount of H. pylori infection (Figure 3B). The mitotic phase was 4/10 high power field with some heterotypes and an obvious nucleolus. Immunohistochemical staining showed tissue cell-like cells positive for S-100, vimentin, CD68, Ki-67 (30%) and negative for CD1a, CD21,Bcl-2, CD3, CD20, CD30, CD45RO, CD117 and PAX-5 (Figure 3C). For further examination, immunohistochemical staining was repeated by the Beijing Cancer Hospital and showed that staining for CD1a was positive for focal lesions (Figure 3D). The shape and immunophenotype indicated Langerhans histiocytosis. Because of the active growth of cancer cells, the patient was referred for medical oncology evaluation for this unusual pathologic finding with malignant potential.

Follow-up gastroscopy 2 mo later showed that the gastric ulcer was in stage S2 (Figure 2D). The mucosal swelling was markedly reduced. Endoscopic ultrasonography showed that the local echo was normal and each layer was clearly divided (Figure 2E). Histopathological examination showed chronic mucosal inflammation with lymphoid tissue hyperplasia in the lamina propria (Figure 3E).

The patient remained asymptomatic, and a follow-up PET-CT was performed 6 mo later. The nodular strong accumulation point with SUV 5.6 in the gastric fundus had disappeared (Figure 1B). Follow-up gastroscopy at the same time showed that the gastric ulcer was in stage S2 (Figure 2F). Histopathological examination revealed that the lesion had chronic mucosal inflammation with acute inflammation (Figure 3F). Therefore, we found no evidence of malignant cancer.

H. pylori infection is a worldwide disease, with about half of the world’s population harboring this bacterium in their stomach. The infection is asymptomatic in most individuals. However, it is the leading cause of non-ulcer dyspepsia, peptic ulcers and gastric tumors[4].

H. pylori is able to survive in the gastric acidic environment because of its ability to synthesize urease, an enzyme which can neutralize the stomach acidic pH. It seems to play a role in the mechanisms which lead to gastric cancer by inducing methylation in different genes, interfering with apoptotic pathways and by causing inflammatory events leading to gastritis, then to atrophic gastritis and possibly to gastric cancer[5]. It may affect the acid secretion of the parietal cells by causing mucosal inflammation. Gastric acid secretion depends on the localization and the degree of the inflammation. Acute infection with H. pylori results in hypochlorhydria, whereas chronic infection can cause either hypo- or hyper-chlorhydria, depending on the distribution of the infection and the degree of corpus gastritis[6]. H. pylori is a powerful carcinogen, since it is able to induce genetic changes, such as hypermethylation events, contributing to cell transformation[5].

H. pylori is well recognized as a class I carcinogen because long-term colonization by this organism can provoke chronic inflammation and atrophy, which can further lead to malignant transformation[7]. Chronic inflammation plays important roles in the development of various cancers, particularly in digestive organs, including H. pylori-associated gastric cancer[8]. During chronic inflammation, H. pylori can induce genetic and epigenetic changes, including point mutations, deletions, duplications, recombinations, and methylation of various tumor-related genes through various mechanisms, which act in concert to alter important pathways involved in normal cellular function, and hence accelerate inflammation-associated cancer development[9]. Alfizah et al[10] reported that variant of H. pylori CagA proteins induce different magnitudes of morphological changes in gastric epithelial cells. In his study, the CagA protein was injected into gastric epithelial cells and supposedly induced morphological changes termed the “hummingbird phenotype”, which is associated with scattering and increased cell motility. The molecular mechanisms leading to the CagA-dependent morphological changes are only partially known[11,12]. The activity of different CagA variants in the induction of the hummingbird phenotype in gastric epithelial cells depends at least in part on EPIYA motif variability. The difference in CagA genotypes might influence the potential of individual CagAs to cause morphological changes in host cells. Depending on the relative exposure of cells to CagA genotypes, this may contribute to the various disease outcomes caused by H. pylori infection in different individuals[10].

Epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that H. pylori infection is associated with increased risk of the development of gastric cancer[13-15]. Animal studies have also shown that H. pylori infection leads to gastric carcinogenesis, especially intestinal phenotypes. Yu et al[16] carried out an in vitro study of cell transformation induced by H. pylori and showed that H. pylori induced morphologic changes in GES-1 cells and significantly increased the proliferation of GES-1 cells. Because the transition from inflamed mucosa to atrophic change is a common route to carcinogenesis, the effect of H. pylori eradication on the incidence of this early precursor lesion is of interest[17]. Since H. pylori infection is associated with gastric carcinoma, therapy is warranted for its eradication[5,18,19].

This was a rare case of a H. pylori-related gastric ulcer that resembled gastric cancer. PET-CT SUV was high, and gastroscopy showed a large ulcer with malignant-like histopathological features. However, after H. pylori eradication treatment, the lesion recovered quickly and follow-up examination showed no evidence of malignant cancer.

P- Reviewers Mimeault M, Guo JM S- Editor Jiang L L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Peterson WL. Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1043-1048. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Egan BJ, Holmes K, O’Connor HJ, O’Morain CA. Helicobacter pylori gastritis, the unifying concept for gastric diseases. Helicobacter. 2007;12 Suppl 2:39-44. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Suzuki RB, Cola RF, Cola LT, Ferrari CG, Ellinger F, Therezo AL, Silva LC, Eterovic A, Sperança MA. Different risk factors influence peptic ulcer disease development in a Brazilian population. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5404-5411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | De Francesco V, Ierardi E, Hassan C, Zullo A. Helicobacter pylori therapy: Present and future. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2012;3:68-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Giordano A, Cito L. Advances in gastric cancer prevention. World J Clin Oncol. 2012;3:128-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Schubert ML. Gastric secretion. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23:595-601. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Lee YC, Chen TH, Chiu HM, Shun CT, Chiang H, Liu TY, Wu MS, Lin JT. The benefit of mass eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection: a community-based study of gastric cancer prevention. Gut. 2012;Jun 14; Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784-789. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Chiba T, Marusawa H, Ushijima T. Inflammation-associated cancer development in digestive organs: mechanisms and roles for genetic and epigenetic modulation. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:550-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Alfizah H, Ramelah M. Variant of Helicobacter pylori CagA proteins induce different magnitude of morphological changes in gastric epithelial cells. Malays J Pathol. 2012;34:29-34. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Lin LL, Huang HC, Ogihara S, Wang JT, Wu MC, McNeil PL, Chen CN, Juan HF. Helicobacter pylori Disrupts Host Cell Membranes, Initiating a Repair Response and Cell Proliferation. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:10176-10192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Matsuhisa T, Aftab H. Observation of gastric mucosa in Bangladesh, the country with the lowest incidence of gastric cancer, and Japan, the country with the highest incidence. Helicobacter. 2012;17:396-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Liu YE, Gong YH, Sun LP, Xu Q, Yuan Y. The relationship between H. pylori virulence genotypes and gastric diseases. Pol J Microbiol. 2012;61:147-150. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Muhammad JS, Zaidi SF, Sugiyama T. Epidemiological ins and outs of helicobacter pylori: a review. J Pak Med Assoc. 2012;62:955-959. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Bhandari A, Crowe SE. Helicobacter pylori in gastric malignancies. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14:489-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yu XW, Xu Y, Gong YH, Qian X, Yuan Y. Helicobacter pylori induces malignant transformation of gastric epithelial cells in vitro. APMIS. 2011;119:187-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kato M, Asaka M. Recent development of gastric cancer prevention. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42:987-994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Malfertheiner P, Selgrad M, Bornschein J. Helicobacter pylori: clinical management. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2012;28:608-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Derakhshan MH, Lee YY. Gastric cancer prevention through eradication of helicobacter pylori infection: feasibility and pitfalls. Arch Iran Med. 2012;15:662-663. [PubMed] |