Copyright

©2012 Baishideng Publishing Group Co.

World J Gastroenterol. Feb 7, 2012; 18(5): 435-444

Published online Feb 7, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i5.435

Published online Feb 7, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i5.435

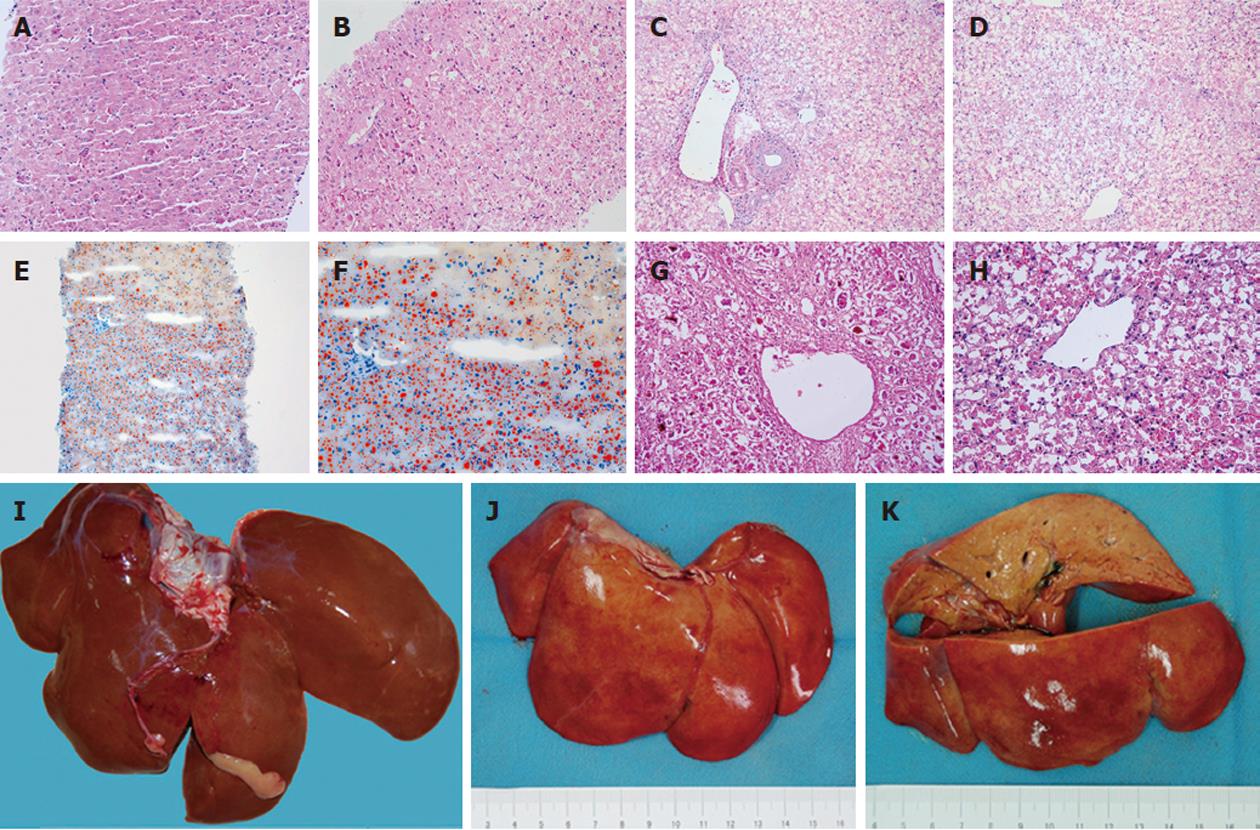

Figure 4 Histopathological changes of the liver.

A: Tissue from needle biopsy at 12 h. Changes in organizational structure and cell morphology were not obvious [hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) stain, × 200]; B: Tissue from needle biopsy at 36 h. Vacuoles appeared in the hepatocellular cytoplasm (H and E stain, × 200); C, D: Tissue from necropsy after death at 70 h. Hepatocellular necrosis was distributed in the portal area (C) and central area (D) (H and E stain, × 200). Massive necrosis caused almost all of the hepatocytes to be lost, and only the support structure remained; E: Frozen tissue from needle biopsy at 36 h. The extensive reddish-orange color suggested serious fatty degeneration (oil red O stain, × 100); F: Frozen tissue from needle biopsy at 36 h. In the borderline between necrosis and steatosis, the reddish-orange color was obvious (oil red O stain, × 200); G, H: Comparison of pathological changes of fulminant hepatic failure in humans induced by viral hepatitis (G) and a Macaca mulatta model induced by α-amanitin and lipopolysaccharide (H) (H and E stain, × 200); I: Normal liver of Macaca mulatta for comparison; J: The surface view of the experimental liver on necropsy appeared red and yellow; K: The cut surface view of the experimental liver was uniformly yellow.

-

Citation: Zhou P, Xia J, Guo G, Huang ZX, Lu Q, Li L, Li HX, Shi YJ, Bu H. A

Macaca mulatta model of fulminant hepatic failure. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(5): 435-444 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i5/435.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i5.435