Published online Feb 21, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i7.922

Revised: October 16, 2010

Accepted: October 23, 2010

Published online: February 21, 2011

AIM: To examine the vitamin D status in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis compared to those with primary biliary cirrhosis.

METHODS: Our retrospective case series comprised 89 patients with alcoholic cirrhosis and 34 patients with primary biliary cirrhosis who visited our outpatient clinic in 2005 and underwent a serum vitamin D status assessment.

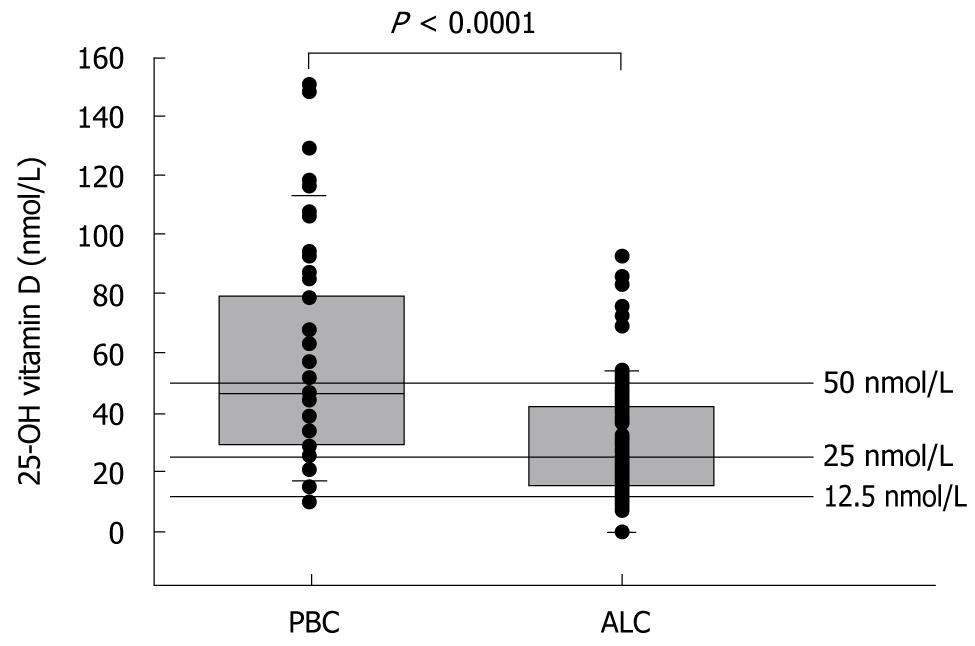

RESULTS: Among the patients with alcoholic cirrhosis, 85% had serum vitamin D levels below 50 nmol/L and 55% had levels below 25 nmol/L, as compared to 60% and 16% of the patients with primary biliary cirrhosis, respectively (P < 0.001). In both groups, serum vitamin D levels decreased with increasing liver disease severity, as determined by the Child-Pugh score.

CONCLUSION: Vitamin D deficiency in cirrhosis relates to liver dysfunction rather than aetiology, with lower levels of vitamin D in alcoholic cirrhosis than in primary biliary cirrhosis.

- Citation: Malham M, Jørgensen SP, Ott P, Agnholt J, Vilstrup H, Borre M, Dahlerup JF. Vitamin D deficiency in cirrhosis relates to liver dysfunction rather than aetiology. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(7): 922-925

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i7/922.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i7.922

Patients with chronic liver disease have an increased risk for the development of osteoporosis and fractures, reduced muscle strength, an impaired inflammatory response, and malignancy[1-3]. These conditions have also been associated with vitamin D deficiency[4-6]. Vitamin D deficiency and osteomalacia have been described in chronic cholestatic liver disease, such as primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC)[7]. However, the frequency of vitamin D deficiency, specifically in alcoholic liver cirrhosis (ALC), has not been well described. The limited available data suggest that there is a high frequency of vitamin D deficiency in patients with chronic liver disease[8,9].

The main source of vitamin D in humans is the exposure of skin to sunlight. For further activation, vitamin D is hydroxylated in the liver to form 25-(OH) vitamin D (25-OHD) and in the kidneys to form the active metabolite 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D. The body stores of vitamin D are best reflected by the serum levels of 25-(OH)D[10].

The aim of the present study was to describe the serum vitamin D status in a retrospective case series of patients with ALC compared to those with PBC. Patients with PBC were considered a priori to demonstrate a high incidence of vitamin D deficiency.

We collected data from the medical records of all patients with a diagnosis of PBC or ALC who visited our outpatient clinic in 2005. A total of 205 patients were identified: 58 had PBC, and 147 had ALC. The study population comprised patients for whom vitamin D measurements had been completed and for whom the Child-Pugh status could be assessed (34 and 89 patients, respectively). In patients who had undergone serial vitamin D measurements, the first blood sample collected in 2005 was used. The vitamin D status was defined according to the following levels of 25-(OH)D: severe deficiency: 0-12.5 nmol/L, deficiency: 12.5-25 nmol/L, insufficiency: 25-50 nmol/L, and vitamin D replete: > 50 nmol/L[11]. Data concerning previous and ongoing vitamin D supplementation were collected from the patients’ medical records. To assess the severity of liver disease, the patients were scored according to the Child-Pugh classification. This score is based on the degree of encephalopathy, the presence of ascites, prothrombin time, and the serum levels of bilirubin, and albumin. The score ranges from 5 to 15 with increasing severity. Accordingly, the patients had either compensated liver disease (Class A, 5-6 points), moderate liver disease (Class B, 7-9 points), or severe liver disease (Class C, 10-15 points).

Plasma 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3 were analysed by isotope-dilution liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry using an API3000 TM mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and a method adapted from Maunsell et al[12]. The interassay variation coefficients for plasma 25(OH)D2 were 8.5% at 23.4 nmol/L and 8.0% at 64.4 nmol/L, and for plasma 25(OH)D3 these values were 9.6% at 24.8 nmol/L and 8.1% at 47.7 nmol/L.

Non-parametric statistics were used for the descriptions, and the Mann-Whitney U test was employed for comparisons between groups. The association between two variables was assessed by the contingency coefficient C, and statistical significance was determined using the χ2 test.

In the patients with ALC, 18% had a severe vitamin D deficiency. In comparison, none of the patients with PBC had such a deficiency. Similarly, in a comparison of patients with ALC and PBC, vitamin D deficiency was identified in 37% vs 16% and vitamin D insufficiency was identified in 30% vs 41% of patients, respectively. Only 15% of patients with ALC were vitamin D replete in comparison to 40% of patients with PBC. The median 25-OHD blood concentration in ALC patients was 24 nmol/L, or 53% of the median serum level of 45 nmol/L in PBC patients (P < 0.001, Mann-Whitney U test) (Figure 1).

Four patients with ALC and 13 patients with PBC were receiving vitamin D supplementation at the time of blood sampling. Their vitamin D levels did not differ from those determined in patients who did not receive supplementation.

The distribution of Child-Pugh groups A, B, and C differed between ALC and PBC patients. Patients with ALC demonstrated more advanced disease (16 A, 36 B, and 37 C) compared to those with PBC (33 A, 1 B, and no C). In all the cirrhotic patients, there was an association between the Child-Pugh score and vitamin D status (contingency coefficient C = 0.29, P < 0.05, χ2 test) (Table 1).

| Vitamin D (nmol/L) | Child-Pugh group | ||

| A | B | C | |

| < 25 | 17 | 15 | 21 |

| 25-50 | 14 | 16 | 12 |

| > 50 | 18 | 6 | 4 |

The vast majority (85%) of patients with ALC presented a compromised vitamin D status. The same was found in fewer than half of the patients with PBC (47%). This finding is in contrast to the standard clinical knowledge that vitamin D deficiency is expected in PBC. Furthermore, this marked vitamin D deficiency has never been demonstrated in a study population of this size.

Our study group included 60% of the cirrhotic patients who were seen at our clinic during 2005. This distribution does not introduce a selection bias because the vitamin D measurements were ordered without physician knowledge of the study purpose. Because the intensity of sunlight changes throughout the year, there might have been a seasonal difference in the vitamin D levels according to when the blood samples were drawn. However, patients were recruited throughout the year in both groups, and therefore, seasonal changes should not affect comparisons between the two groups.

The observed deficiency in vitamin D might be related to several causes: an impaired hepatic hydroxylation of vitamin D, dietary insufficiency, malabsorption, reduced hepatic production of vitamin D binding protein, and an impaired cutaneous production due to either reduced exposure to sunlight or jaundice[9,13]. The observation that the deficiency was less pronounced in PBC patients suggests that bile acid-related lipid malabsorption is not the only mechanism involved in vitamin D deficiency. It seems plausible that the mechanism of vitamin D deficiency is multifactorial and differs between the two groups of cirrhotic patients. When the results were stratified according to the Child-Pugh class, an association was observed between vitamin D deficiency and the severity of liver disease. This association has never been demonstrated in such a large study population. Thus, the better preservation of vitamin D status in patients with PBC might be ascribed to the diminished severity of their liver disease, as assessed by their Child-Pugh scores. Based on this finding, one could hypothesise that the risk for vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency might be influenced more by the degree of liver dysfunction than by the aetiology of the liver disease. However, our study was not designed to elucidate the exact mechanism underlying the vitamin D deficiency. The purpose of the study was to emphasise the importance of monitoring the vitamin D status in all patients with cirrhosis, especially those with ALC for whom nutritional status has been a relatively neglected area of study.

Our results imply that vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent in patients with ALC. Because this was a retrospective study, we cannot extrapolate the results to the general population of cirrhotic patients. However, these results indicate that the frequency and severity of vitamin D deficiency in ALC patients warrant greater attention, similar to the usual clinical practice in patients with PBC.

Although 17 of the study patients received vitamin D supplementation, this supplementation was clearly insufficient, as their vitamin D concentrations remained low. Thus, it appears that the vitamin D deficiency in these patients should be treated with higher doses of vitamin D than that used in standard clinical practice for repletion.

The risk for bone disease in cirrhotic patients justifies the use of routine vitamin D therapy. Furthermore, the patients might also benefit from correction of their vitamin D status with respect to reduced muscle function, cancer risk, and immune impairment.

Patients with liver cirrhosis have an increased incidence of cancer, infections, osteoporosis, and decreased muscle strength. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with these complications in other patient groups and could be partially involved in the clinical complications related to cirrhosis.

Vitamin D deficiency is a well reported complication in chronic cholestatic liver disease such as primary biliary cirrhosis. While the prevalence and treatment of this deficiency has been addressed in many articles over the last decades, little is known of the vitamin D status in alcoholic liver cirrhosis.

Recent studies imply that vitamin D deficiency is frequent in all patients with cirrhosis. The current study shows that vitamin D deficiency is more frequent and severe in patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis than in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Furthermore, it indicates that the degree of liver dysfunction, rather than the aetiology of cirrhosis, dictates the risk of vitamin D deficiency.

This study emphasizes the importance of monitoring vitamin D levels in all patients with cirrhosis. However, further studies are needed to find the most favourable form of vitamin D supplementation for these patients.

Primary biliary cirrhosis and alcoholic cirrhosis are two different diseases that cause cirrhosis of the liver. While primary biliary cirrhosis is a cholestatic, autoimmune disease, alcoholic liver cirrhosis is an alcohol-induced liver disease usually without cholestatic features. The Child-Pugh score assesses the prognosis in patients with cirrhosis and is also used to quantitate the degree of liver dysfunction.

This brief article nicely demonstrated the association of the liver damage severity with the level of 25-hydroxy vitamin D. This is a very important report, as many doctors do not realize that liver damage could cause significant vitamin D deficiency.

Peer reviewer: Lixin Zhu, MD, State University of New York, 3435 Main Street, 422 BRB, Buffalo, 14214 New York, United States

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Ormarsdóttir S, Ljunggren O, Mallmin H, Michaëlsson K, Lööf L. Increased rate of bone loss at the femoral neck in patients with chronic liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:43-48. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Sorensen HT, Friis S, Olsen JH, Thulstrup AM, Mellemkjaer L, Linet M, Trichopoulos D, Vilstrup H, Olsen J. Risk of liver and other types of cancer in patients with cirrhosis: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Hepatology. 1998;28:921-925. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Wasmuth HE, Kunz D, Yagmur E, Timmer-Stranghöner A, Vidacek D, Siewert E, Bach J, Geier A, Purucker EA, Gressner AM. Patients with acute on chronic liver failure display "sepsis-like" immune paralysis. J Hepatol. 2005;42:195-201. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Glerup H, Mikkelsen K, Poulsen L, Hass E, Overbeck S, Andersen H, Charles P, Eriksen EF. Hypovitaminosis D myopathy without biochemical signs of osteomalacic bone involvement. Calcif Tissue Int. 2000;66:419-424. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Holick MF. Sunlight and vitamin D for bone health and prevention of autoimmune diseases, cancers, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1678S-1688S. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Lappe JM, Travers-Gustafson D, Davies KM, Recker RR, Heaney RP. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation reduces cancer risk: results of a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1586-1591. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Reed JS, Meredith SC, Nemchausky BA, Rosenberg IH, Boyer JL. Bone disease in primary biliary cirrhosis: reversal of osteomalacia with oral 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:512-517. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Crawford BA, Kam C, Donaghy AJ, McCaughan GW. The heterogeneity of bone disease in cirrhosis: a multivariate analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:987-994. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Fisher L, Fisher A. Vitamin D and parathyroid hormone in outpatients with noncholestatic chronic liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:513-520. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Crawford BA, Labio ED, Strasser SI, McCaughan GW. Vitamin D replacement for cirrhosis-related bone disease. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;3:689-699. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Lips P. Which circulating level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D is appropriate? J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;89-90:611-614. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Maunsell Z, Wright DJ, Rainbow SJ. Routine isotope-dilution liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry assay for simultaneous measurement of the 25-hydroxy metabolites of vitamins D2 and D3. Clin Chem. 2005;51:1683-1690. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Pappa HM, Bern E, Kamin D, Grand RJ. Vitamin D status in gastrointestinal and liver disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:176-183. [Cited in This Article: ] |