Published online Aug 14, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i30.3544

Revised: May 20, 2011

Accepted: May 27, 2011

Published online: August 14, 2011

AIM: To investigate and review the contrast-enhanced multiple-phase computed tomography (CEMP CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings in patients with pathologically confirmed hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (HEHE).

METHODS: Findings from imaging examinations in 8 patients (5 women and 3 men) with pathologically confirmed HEHE were retrospectively reviewed (CT images obtained from 7 patients and MR images obtained from 6 patients). The age of presentation varied from 27 years to 60 years (average age 39.8 years).

RESULTS: There were two types of HEHE: multifocal type (n = 7) and diffuse type (n = 1). In the multifocal-type cases, there were 74 lesions on CT and 28 lesions on MRI with 7 lesions found with diffusion weighted imaging; 18 (24.3%) of 74 lesions on plain CT and 26 (92.9%) of 28 lesions on pre-contrast MRI showed the target sign. On CEMP CT, 28 (37.8%) of 74 lesions appeared with the target sign and a progressive-enhancement rim and 9 (12.2%) of 74 lesions displayed progressive enhancement, maintaining a state of persistent enhancement. On CEMP MRI, 27 (96.4%) of 28 lesions appeared with the target sign with a progressive-enhancement rim and 28 (100%) of 28 lesions displayed progressive-enhancement, maintaining a state of persistent enhancement. In the diffuse-type cases, an enlarged liver was observed with a large nodule appearing with persistent enhancement on CEMP CT and MRI.

CONCLUSION: The most important imaging features of HEHE are the target sign and/or progressive enhancement with persistent enhancement on CEMP CT and MRI. MRI is advantageous over CT in displaying these imaging features.

- Citation: Chen Y, Yu RS, Qiu LL, Jiang DY, Tan YB, Fu YB. Contrast-enhanced multiple-phase imaging features in hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(30): 3544-3553

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i30/3544.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i30.3544

Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (HEHE) is a rare vascular tumor in adults with a variable but often long clinical course, which is intermediate between hemangioma and angiosarcoma in clinical biological behavior[1]. This tumor is histologically characterized by an epithelial appearance and endothelial nature in tumor cells[1]. Clinical, imaging and pathologic diagnosis of HEHE is difficult[2-4], however, its correct diagnosis is very important because long-term survival (5-10 years) of HEHE is possible[5]. Treatment modalities include hepatic resection, orthotopic liver transplantation (even in cases with known metastases), radiotherapy, chemotherapy and use of interferon alpha-2[3,6].

No more than 200 cases of HEHE have been reported since its first description[1-19] and most of them were of sporadic cases and small case series[1,2,8,10,12-15]. The contrast-enhanced multiple-phase computed tomography (CEMP CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of HEHE have not been well addressed. In this paper, we highlight the predominant imaging features of this type of tumor, focusing on the target sign and/or progressive enhancement with persistent enhancement on CEMP CT and MRI, which have not been extensively described previously in the English-language literature, to the best of our knowledge.

CT (n = 7), MRI (n = 6), clinical (n = 8) and pathological (n = 8) features of 8 cases of HEHE were retrospectively reviewed at our institution from 2004 to 2009. This study was approved by the Institutional Research and Ethics Board of our institution. Among the 8 cases, there were 3 males and 5 females, with ages ranging from 27 to 57 years (mean, 39.8 years). The duration of symptoms ranged from 10 d to 2 years.

The clinical signs and symptoms included epigastric pain (n = 2), discomfort (n = 3), weight loss (n = 3), weakness (n = 2), hepatomegaly (n = 5), splenomegaly (n = 4) and ascites (n = 1). Two patients without any complaints were incidentally found by a routine physical examination. One of 8 cases was accompanied by lung epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Laboratory tests showed abnormal liver function in two cases, with mild elevation of serum bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase and aspartate aminotransferase levels. HBsAg was positive in two patients. Tumor marker levels, including α-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and cancer antigen 19-9, were negative in all patients except for an increased level of CEA in one patient.

CT imaging was performed in seven patients using Siemens Somatom Sensation 16-row CT scanners with 5-mm axial sections from the dome of the diaphragm to the last plane of the liver. All patients were examined in a fasting state with plain scanning at first, and then non-ionic contrast medium (Omnipaque 300 g/L, GE Healthcare, USA) 80 mL per bolus injection was given via antecubital vein for enhanced scanning. Images were obtained separately at the arterial phase (25-35 s after injection), portal venous phase (65-75 s after injection) and equilibrium phase (100-110 s after injection).

MR scanning was performed using a 1.5 T or 3.0 T magnet (Signa, GE Healthcare, USA) with an eight-channel torso-array coil. Axial T1-weighted images (T1WI) and T2-weighted images (T2WI) were obtained from all six patients, and additional contrast-enhanced T1WI (Omniscan, GE Healthcare, USA, 0.1 mmol/kg body weight) images were obtained from four patients. Dynamic breath-hold T1WI acquisitions were obtained at 15-27 s, 40-52 s, 70-82 s and 130-142 s after contrast enhancement. The imaging parameters for T1WI and T2WI were as follows: repetition time/echo time (TR/TE) of 205/3.2 ms and 6000/102.5 ms. The matrix was 256 × 256, the standard field-of-view was 400 mm and slice thickness was 4.0 mm with no interslice gap. Additional diffusion weighted single-shot echo-planar imaging was performed in two patients using the following parameters: TR/TE = 1300/52.5 ms, 7-8 mm thickness, water selective excitation for fat suppression, matrix size = 128 × 128, field of view = 36 cm × 36 cm, number of excitations = 6.0, slice thickness/gap = 5 mm/1.0 mm, 20 axial slices, scan time = 2 min 24 s, b value = 0 and 600 s/mm2, under breath-hold.

All CT and MR images were reviewed separately by two radiologists who were blinded to the identity of the patient and clinical outcome. Discordance between the two was resolved by consensus.

Histologic specimens of HEHE were obtained by percutaneous needle biopsy in five patients and by exploratory laparotomy and nodule biopsy in three patients. HEHE was diagnosed on the basis of light microscopic examinations of histologic specimens. HE staining and immunohistochemical staining for at least one endothelial marker, i.e., factor VIII-related antigen, CD34, or CD31, were performed on all tumors to confirm the endothelial origin[2,8]. All HEHE specimen analyses were confirmed by an experienced pathologist for diagnostic accuracy.

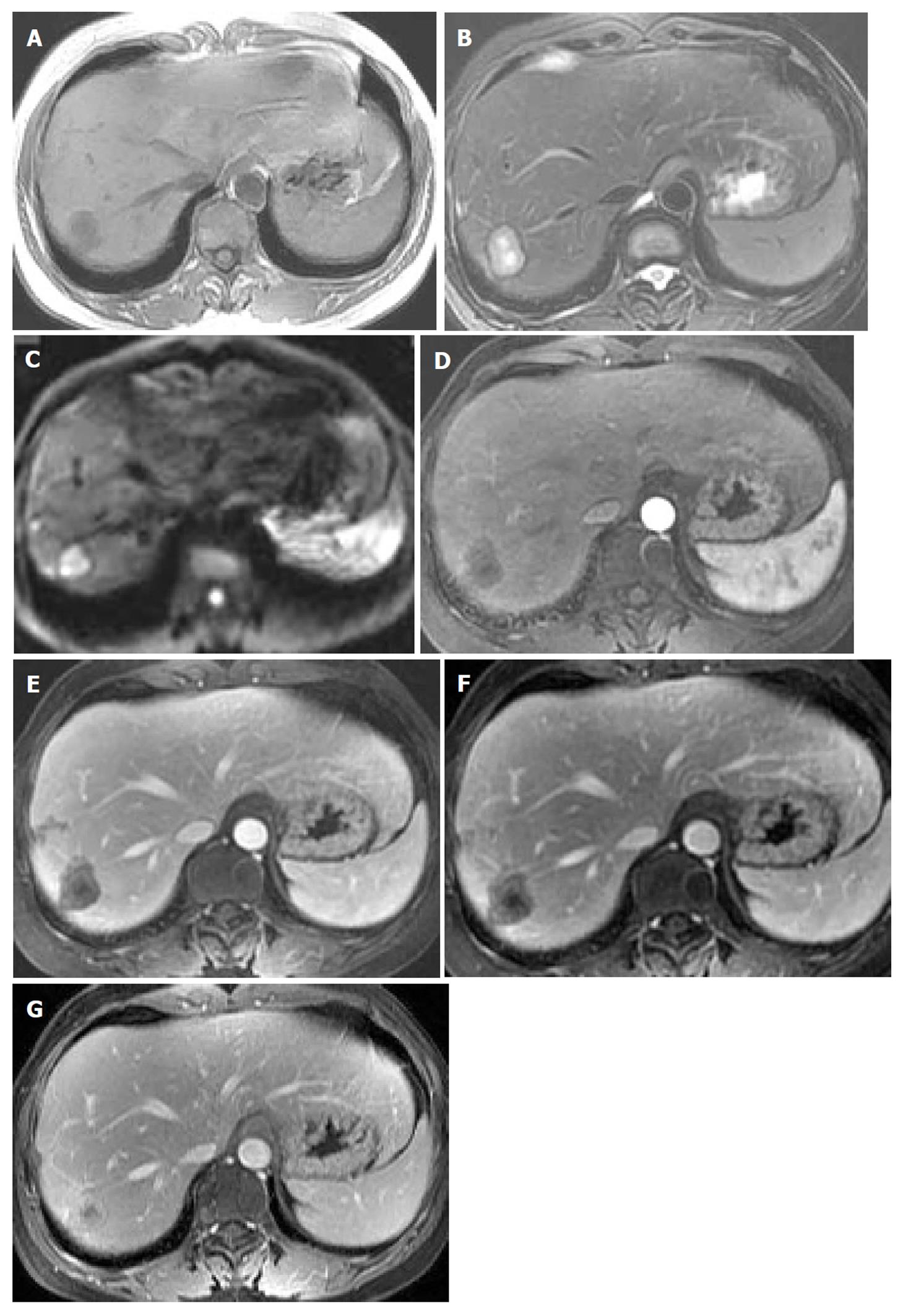

There were two types of HEHE in the 8 cases of our study: multifocal type (n = 7) and diffuse type (n = 1). In the 7 multifocal type cases, a total of 74 lesions were found with CT, 28 lesions with MRI and 7 with diffusion weighted imaging (DWI). Eighteen (24.3%) of 74 lesions on plain CT showed a low density with peripheral isodensity (Figure 1A), which looked like a “target” with an inner low density/intensity and a peripheral hyper-density/intensity or isodensity/intensity (target sign).

On CEMP CT images, 28 (37.8%) of 74 lesions showed peripheral ring-like enhancement in the arterial phase with even stronger enhancement in the portal venous and equilibrium phases, appearing as a target sign with a progressive-enhancement rim (Figures 1B and C). Nine (12.2%) of 74 lesions displayed progressive enhancement, with 8 (10.8%) lesions showing progressive enhancement in the center and 1 (1.4%) lesion showing lamellar progressive enhancement on CEMP CT, maintaining the state of persistent enhancement.

Twenty-six (92.9%) of 28 lesions showed hypointensity relative to normal liver parenchyma with peripheral faint hyperintensity on T1WI (Figure 2A) and hyperintensity with peripheral hypointensity and an area of evident hyperintensity in the center on T2WI (Figure 2B), appearing as the target sign. Six (85.7%) of 7 lesions showed hyperintensity with a peripheral hypointense rim on DWI (Figure 2C) and 1 (14.3%) showed lamellar hyperintensity on DWI.

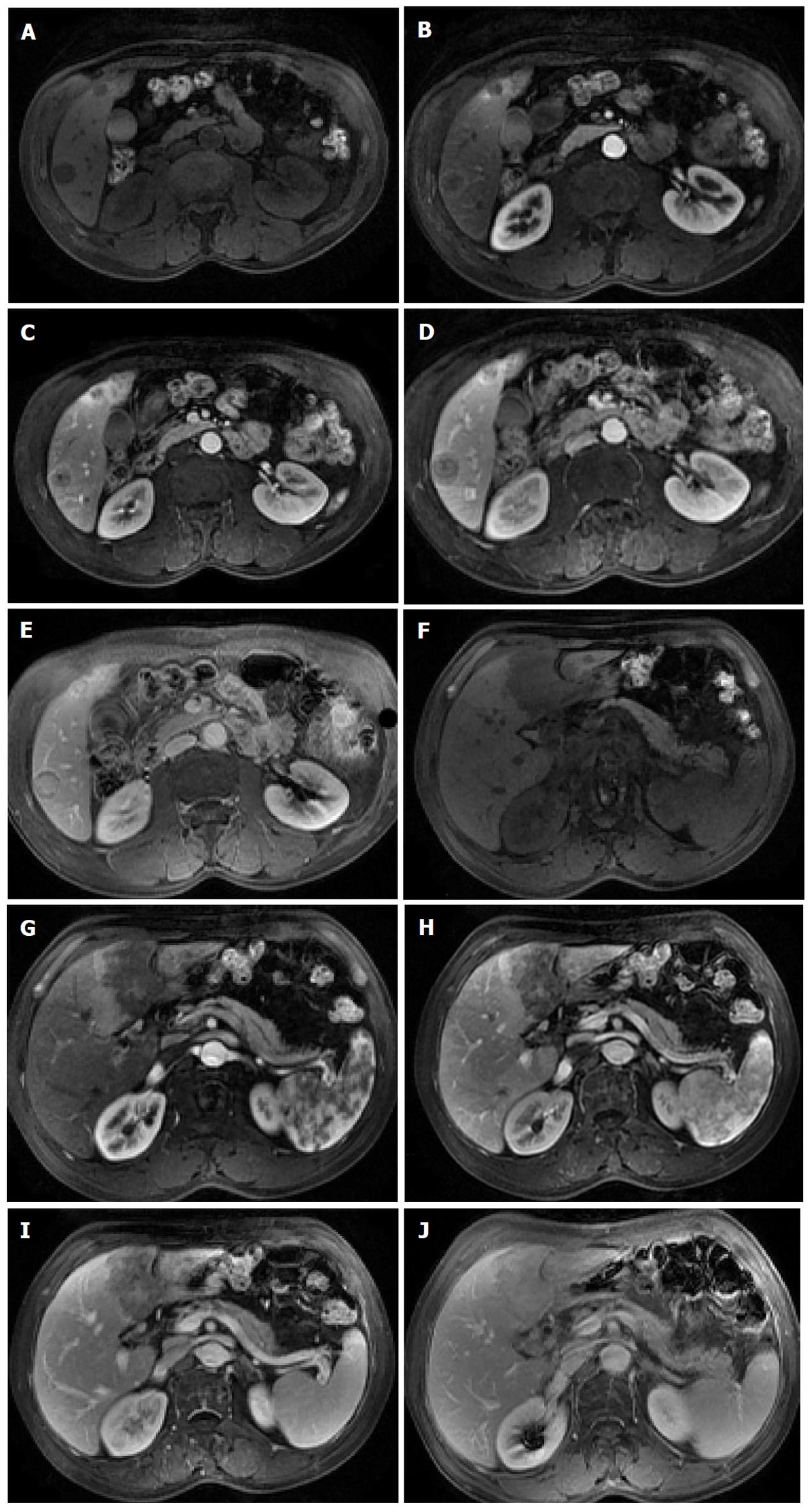

On CEMP MRI, 27 (96.4%) of 28 lesions displayed peripheral ring-like enhancement in the arterial phase, and even stronger enhancement in the portal venous and equilibrium phases, appearing as a target sign with a progressive-enhancement rim; 28 (100%) of 28 lesions displayed progressive-enhancement in the arterial, portal venous and equilibrium phases and became isointense to liver parenchyma in the delayed phase, with 27 (96.4%) lesions showing progressive enhancement in the center of the target (Figures 2D-G, Figures 3A-E) and 1 (3.6%) lesion showing lamellar progressive enhancement on CEMP MRI (Figures 3F-J), maintaining the state of persistent enhancement.

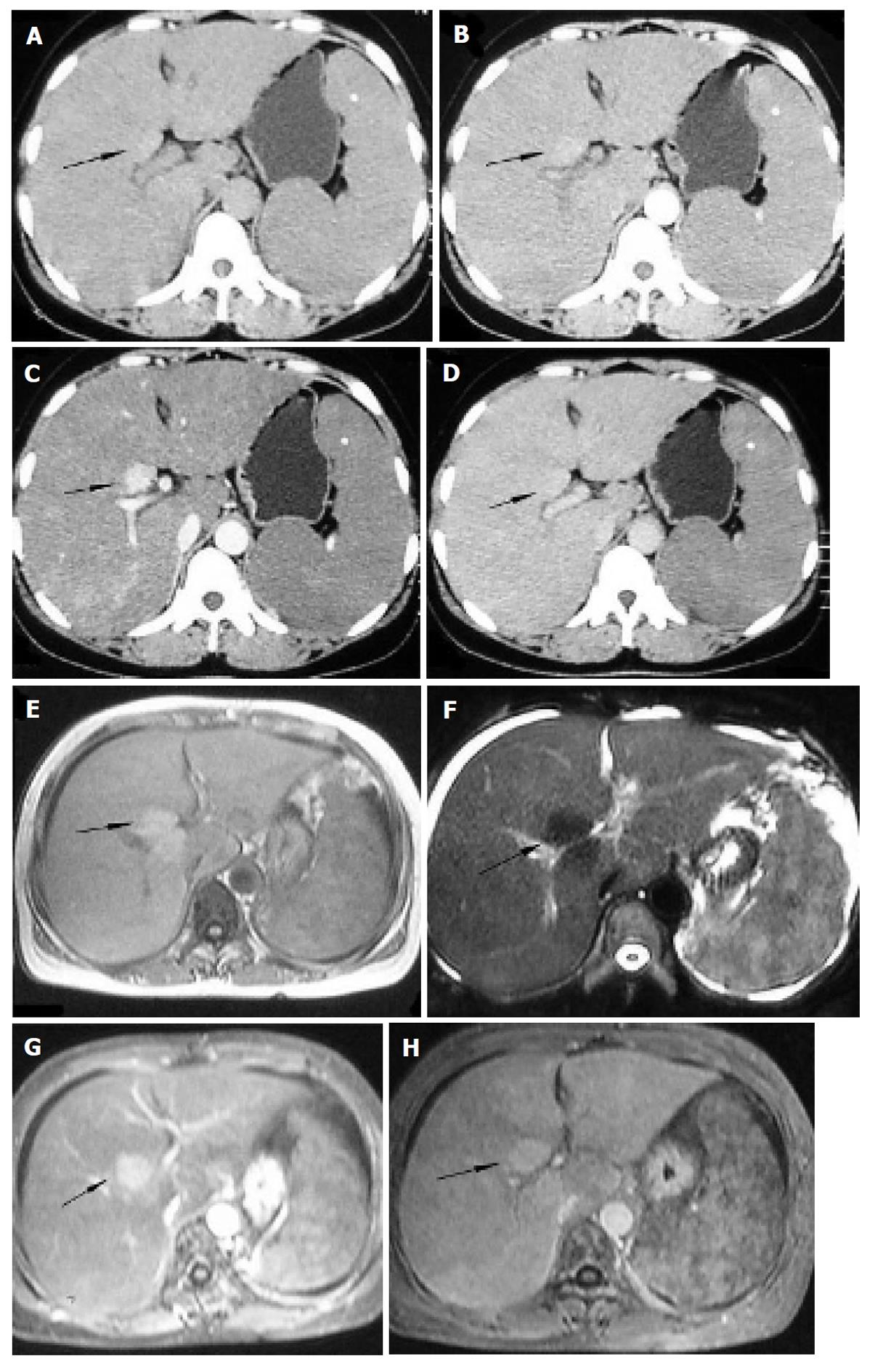

One diffuse case manifested an enlarged liver with a large nodule appearing slightly hyperdense relative to normal liver parenchyma on plain CT (Figure 4A), isointensity on T1WI (Figure 4E) and hypointensity on T2WI (Figure 4F), with slight enhancement in the arterial phase (Figure 4B), evident enhancement in the portal venous phase (Figures 4C and G) and isodense/intense in the equilibrium phase (Figures 4D and H), which manifested persistent enhancement on CEMP CT and MRI, associated with splenomegaly and ascites (Figure 4F). All the imaging features are summarized in Table 1.

| Cases | Sex | Age (yr) | Total lesion (n) | Plain CT findings of HEHE | Pre-enhanced MRI of HEHE | CEMP imaging findings of HEHE | Radiological findings of extra-hepatic lesions | |

| Lesions of target sign with peripheral progressive enhancement (n) | Lesions of central or lamellar progressive enhancement (n) | |||||||

| Case 1 multifocal-type (Figure 1) | Male | 27 | 42 | All discrete, peripheral, low-attenuation lesions with 1 coalescence and 13 target sign | No MRI obtained | 42 | 0 | No extra-hepatic lesions |

| Case 2 multifocal-type | Female | 30 | 14 | All discrete, peripheral, low-attenuation lesions with 1 coalescence and 5 target sign | All lesions showing hypointense on T1WI and hyperintense on T2WI with 14 target sign | 3 (CT), 14 (MRI) | 3 (CT), 14 (MRI) | No extra-hepatic lesions |

| Case 3 multifocal-type | Female | 28 | 2 | All discrete, peripheral, low-attenuation lesions | No MRI obtained | 2 (CT), 2 (MRI) | 2 (CT), 2 (MRI) | No extra-hepatic lesions |

| Case 4 multifocal-type | Female | 53 | 4 | All discrete, peripheral, low-attenuation lesions | No MRI obtained | 4 (CT) | 0 | No extra-hepatic lesions |

| Case 5 multifocal-type (Figure 2) | Female | 48 | 10 | All discrete, peripheral, low-attenuation lesions with 1 coalescence | All lesions showing hypointense on T1WI and hyperintense on T2WI with 10 target sign, and 5 hyperintense with peripheral hypointense on DWI | 10 (CT), 10 (MRI) | 4 (CT), 10 (MRI) | No extra-hepatic lesions |

| Case 6 multifocal-type | Female | 56 | 2 | All discrete, peripheral, low-attenuation lesions, with compensatory hypertrophy in the left lobe of liver | No MRI obtained | 0 | 2 (CT) | Pleural effusion in both sides |

| Case 7 multifocal-type (Figure 3) | Male | 60 | 2 | No CT obtained | Two lesions showing hypointense on T1WI and hyperintense on T2WI, and 1 hyperintense with peripheral hypointense on DWI | 1 (MRI) | 2 (MRI) | No extra-hepatic lesions |

| Case 8 diffuse –type (Figure 4) | Female | 48 | Diffuse | Diffuse hepatomegaly with a slightly hyperdense nodule | Diffuse hepatomegaly with a nodule appearing isointense on T1WI and hypointense on T2WI | Diffuse hepatomegaly with a nodule appearing persistent enhancement | Splenomegaly and ascites | |

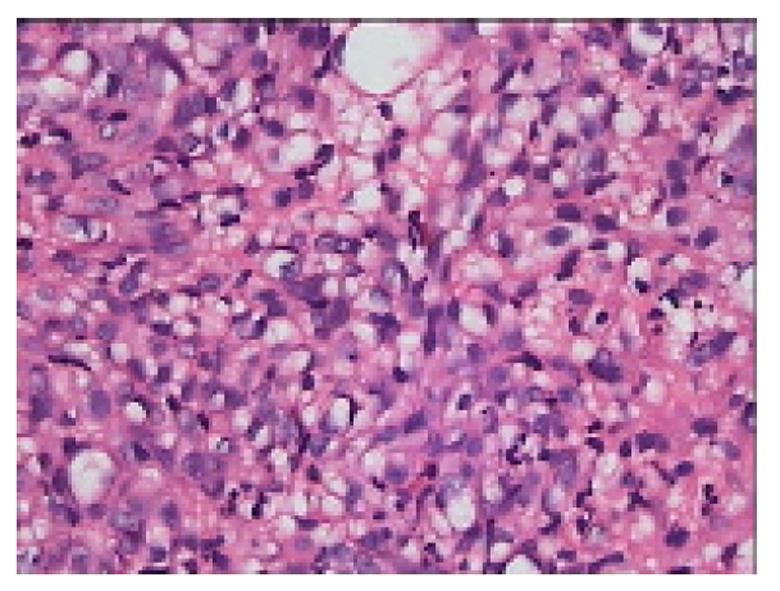

All tumors were consistent with a diagnosis of HEHE on pathological review. Grossly, the tumors were solid, firm and hyperemic in the outer portions. Histologically, the tumors were composed of dendritic and epithelioid cells. Signet ring–like structures appeared in the tumor cells with intracytoplasmic lumina, occasionally containing red blood cells (Figure 5). The tumors consisted of large amounts of mucinous and dense stroma in the center and rich cellular zones in the periphery. Immunohistochemically, tumors were positive for factor VIII-related antigen in 3 patients (Figure 6A), CD34 in 5 patients (Figure 6B) and CD31 in 4 patients (Figure 6C). Tumors were negative for epithelial markers (cytokeratin and CEA).

HEHE is a rare tumor of vascular origin, first defined as a specific entity by Weiss and Enzinger in 1982[5]. Because of the prolonged course and nonspecific clinical manifestations, the age of the patients varies greatly at the time of HEHE detection by biopsy or imaging studies. The incidence of this neoplasm is higher in females than in males (a female to male ratio of 3:2), with a peak incidence occurring between 30 and 40 years of age[2]. Most patients survive 5-10 years after diagnosis[4]. This study covered 5 females and 3 males and their average age was 39.8 years, which was comparable with other reports in the literature.

Clinical manifestation is variable, with most showing nonspecific symptoms such as right upper quadrant pain and weight loss. Physical examination findings are uncommon but may include hepatomegaly, a palpable mass, or jaundice. Some patients present with hemoperitoneum[20] and Budd-Chiari syndrome due to hepatic vein invasion[9]; others present with incidental findings[2]. Liver function tests reveal mild abnormalities in most patients. Tumor marker levels are negative apart from elevated CEA levels in a small number of patients, which is in conformity with our series. No risk factors or specific causes of HEHE were identified. Two patients in our study were HBsAg positive, which is similar to the rate reported in a few studies[10]. However, more cases are needed to clarify the relationship between HBV infection and the occurrence of HEHE.

Pathologically, there are three types of growth patterns in the gross appearance of HEHE: multiple nodules, diffuse nodules and a single mass[3,8,11]. Histologically, the tumors are composed of dendritic and epithelioid cells. Immunohistochemically, tumors are positive for factor VIII-related antigen, CD34 or CD31, demonstrating the endothelial origin of these tumors[2,8]. Two types of HEHE were found in our cases, i.e., multifocal and diffuse, and the immunohistochemical results of our series were consistent with other observations. HEHE may have been present in some patients with pulmonary EHE or soft tissue EHE, but was considered metastatic[5,21-23]. In our series, there was one case of HEHE associated with pulmonary EHE.

A few radiological findings in HEHE have been described[1,2,8,10,12-15], however, CEMP CT and MRI findings have not been well addressed. According to the literature on multifocal-pattern HEHE[1,2,8,12,13], plain CT usually shows multiple discrete low-attenuation lesions and extensive confluent masses. Contrast-enhanced CT findings include marginal enhancement during the arterial phase[12], becoming isodense to liver parenchyma on contrast-enhanced scans[8], and a halo or target pattern of enhancement with larger lesions[1,13]. Lin et al[10] found that about 38 (48.1%) of 79 lesions showed the “halo” sign on contrast-enhanced CT. We had similar findings with CT, but 24.3% of the lesions showed the target sign on plain CT, 37.8% lesions showed the target sign with a progressive-enhancement rim and 12.2% lesions displayed progressive enhancement on CEMP CT, maintaining the state of persistent enhancement. The CT findings in our cases were not compatible with other reports in the literature.

According to the literature on multifocal pattern HEHE[1,2,8,12,13], precontrast MR imaging revealed hypointense lesions relative to normal liver parenchyma on unenhanced T1-weighted images, heterogeneously increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images and hyperintensity with peripheral hypointensity on DWI[7,8]. Some lesions have a peripheral halo or a target-type enhancement pattern on enhanced MR imaging, with occasional observation of a thin peripheral hypointense rim[2,8,12]. Lin et al[10] found that 9 (23.1%) of 39 lesions presented the characteristic “halo” sign on contrast-enhanced MRI. In our series, we had similar findings with precontrast MRI and DWI, but 92.9% of the lesions showed the target sign on precontrast MRI and 14.3% of the lesions showed lamellar hyperintensity on DWI, which is in contrast to the previous literature. In our series, 96.4% of the lesions appeared with the target sign and a progressive-enhancement rim and 100% of the lesions displayed progressive-enhancement, maintaining the state of persistent enhancement. The MRI findings in our cases were not compatible with the previous literature. The MRI features of progressive reinforcement on CEMP MRI have not been reported previously according to our literature search.

It could be considered that the distinctive image appearance of the tumor is correlated with the pathologic characteristics in many ways. Histologically, the tumors consisted of large amounts of mucinous and dense stroma in the center and rich cellular zones in the periphery. These findings might account for the central low density and peripheral isodensity on plain CT images, hypointensity with peripheral faint hyperintensity on T1WI and hyperintensity with peripheral hypointensity on T2WI and DWI. The actively proliferating, increased cellular periphery of the nodules may account for the peripheral progressive-enhancement target sign on CEMP CT. The tumor also produced a fibrous myxoid stroma that was most dense in the center of the nodules, which may attribute to the heterogeneously progressive reinforcement on CEMP MRI. Tumor infiltration and occlusion of hepatic sinusoids and small vessels caused a narrow avascular zone between the tumor nodules and liver parenchyma. This may be the reason for the halo appearance on CT or MRI.

According to the reported studies on diffuse-pattern HEHE, a multifocal nodular pattern of infiltration is usually considered as the early stage of a diffuse pattern[1,8,13]. Local lesions may increase in size and coalesce, thus forming the diffuse pattern. The diffuse lesions contain many lowly attenuating, round or irregular spots, which may be associated with calcified foci and dilated bile ducts in the lesions. The lesions were slightly enhanced on dynamic CT scans and became iso-attenuated to non-tumorous liver on subsequent scans, but spots of lower attenuation remained inside or showed marked contrast enhancement during and after intra-arterial contrast material injection and disappeared within 1 min after the contrast material injection. In our series, the diffuse case was also associated with splenomegaly and ascites, but had different imaging findings manifesting an obviously enlarged liver with a large nodule. The manifestation of diffuse-pattern HEHE appearing as an obviously enlarged liver was only reported by Lorber et al[11]. Necropsy showed that the liver was grossly enlarged without cirrhosis, and contained a very discrete red area (0.2-2.5 cm in diameter). However, according to our search, the MRI findings of diffuse-pattern HEHE with a large nodule and the imaging feature of a large nodule manifesting persistent enhancement on CEMP CT and MRI have not been reported previously.

Because the histologic specimens of this diffuse-pattern HEHE were obtained by percutaneous needle biopsy of many sites in the liver, but not with exploratory laparotomy, it is hard to analyze the correlation between the imaging findings of the large nodule in a diffuse case with the pathologic findings. We suppose that the large nodule in the diffuse case might consist of large amounts of tumor cells, manifesting persistent enhancement on CEMP CT and MRI, and the nodule appearing slightly hyper-dense on plain CT, isointense on T1WI and hypointense on T2WI might correlate with hemorrhage in the nodule.

According to the isolated case report literature of single-pattern HEHE, it only accounted for about 18%[3]. Jeong et al[14] and Hsieh et al[15] found that the single lesion is usually ovoid, with a low density and calcification in segment 7 of the liver in the pre-contrast phase of liver dynamic CT. The mass exhibited central enhancement in the arterial phase, heterogeneous peripheral enhancement in the portal phase, and then peripheral enhancement was washed out in the delayed phase, or with central enhancement in the delayed phase on CT. According to these reports, the single nodular pattern of HEHE typically preferentially involved the right lobe of the liver, and the pattern of contrast enhancement was different and more studies are needed in the future. To our regret, there was no single-pattern HEHE in our cases.

For differential diagnosis, the most important imaging features of a target sign and progressive enhancement could differentiate HEHE from intrahepatic multiple metastatic tumors, cavernous hemangioma and primary hepatic angiosarcoma.

In conclusion, MRI is more advantageous over CT in displaying the imaging features of a target sign and progressive enhancement. Although the incidence of HEHE is low and the diagnosis can only be confirmed by pathological examination, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis list of intrahepatic nodules appearing with a target sign and/or progressive enhancement with persistent enhancement on CEMP CT and MRI, which demonstrates a vasoformative nature, especially in multiple lesions in middle-aged women.

Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (HEHE) is a rare vascular tumor. Clinical assessment, imaging and pathologic diagnosis of HEHE is difficult, however, its correct diagnosis is very important because long-term survival of HEHE is possible.

No more than 200 cases of HEHE have been reported since its first description. The contrast-enhanced multiple-phase computed tomography (CEMP CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of HEHE have not been well addressed. In this study, the authors highlight the predominant imaging features of this tumor, which have not been described previously in the English-language literature.

Most of the radiologic studies on HEHE were sporadic case reports and small case series reports. In this study, the authors evaluated and described target sign and/or progressive enhancement with persistent enhancement in CEMP CT and MRI of HEHE. MRI is advantageous over CT in displaying these imaging features. Furthermore, the authors described a diffuse-type HEHE, manifesting diffuse hepatomegaly with a slightly hyperdense nodule appearing with persistent enhancement on CEMP CT and MRI.

By demonstrating imaging features of HEHE on CEMP CT and MRI, this study may represent a future strategy for correct diagnosis of HEHE and therapeutic intervention in the treatment of HEHE.

A target sign is an image that looks like a “target” with inner density/intensity and peripheral hyper-density/intensity or iso-density/intensity. On CEMP CT and MRI, it appears as peripheral ring-like and progressive enhancement. In some typical cases, it may show hyperintensity with peripheral hypointensity and an area of evident hyperintensity in the center on T2WI or an area of unenhanced necrosis in the center.

The authors investigated and described CEMP CT and MRI findings in patients with pathologically confirmed HEHE. It revealed the most important imaging features of HEHE may be a target sign and/or progressive enhancement with persistent enhancement on CEMP CT and MRI. MRI is advantageous over CT in displaying these imaging features. The results are interesting and may represent the imaging features in HEHE.

Peer reviewer: Utaroh Moto, Assistant Professor, Department of Radiology, University of Yamanashi, 1110 Shimokato, 409-3898 Chuo-shi, Japan

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Zhang L

| 1. | 1 Furui S, Itai Y, Ohtomo K, Yamauchi T, Takenaka E, Iio M, Ibukuro K, Shichijo Y, Inoue Y. Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: report of five cases. Radiology. 1989;171:63-68. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Earnest F, Johnson CD. Case 96: hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Radiology. 2006;240:295-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Makhlouf HR, Ishak KG, Goodman ZD. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver: a clinicopathologic study of 137 cases. Cancer. 1999;85:562-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ishak KG, Sesterhenn IA, Goodman ZD, Rabin L, Stromeyer FW. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver: a clinicopathologic and follow-up study of 32 cases. Hum Pathol. 1984;15:839-852. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Weiss SW, Enzinger FM. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: a vascular tumor often mistaken for a carcinoma. Cancer. 1982;50:970-981. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Uchimura K, Nakamuta M, Osoegawa M, Takeaki S, Nishi H, Iwamoto H, Enjoji M, Nawata H. Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:431-434. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Bruegel M, Muenzel D, Waldt S, Specht K, Rummeny EJ. Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: findings at CT and MRI including preliminary observations at diffusion-weighted echo-planar imaging. Abdom Imaging. 2011;36:415-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lyburn ID, Torreggiani WC, Harris AC, Zwirewich CV, Buckley AR, Davis JE, Chung SW, Scudamore CH, Ho SG. Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: sonographic, CT, and MR imaging appearances. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:1359-1364. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Fukayama M, Nihei Z, Takizawa T, Kawaguchi K, Harada H, Koike M. Malignant epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver, spreading through the hepatic veins. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1984;404:275-287. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Lin J, Ji Y. CT and MRI diagnosis of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2010;9:154-158. [PubMed] |

| 11. | LORBER J, ACKERLEY AG. Malignant haemangioendotheliomata simulating miliary tuberculosis and neuroblastoma of the adrenal. Proc R Soc Med. 1958;51:288-290. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Miller WJ, Dodd GD, Federle MP, Baron RL. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver: imaging findings with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:53-57. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Radin DR, Craig JR, Colletti PM, Ralls PW, Halls JM. Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Radiology. 1988;169:145-148. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Jeong SW, Woo HY, You CR, Huh WH, Bae SH, Choi JY, Yoon SK, Jung CK, Jung ES. [A case of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma that caused extrahepatic metastases without intrahepatic recurrence after hepatic resection]. Korean J Hepatol. 2008;14:525-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hsieh MS, Liang PC, Kao YC, Shun CT. Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma in Taiwan: a clinicopathologic study of six cases in a single institution over a 15-year period. J Formos Med Assoc. 2010;109:219-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yu RS, Chen Y, Jiang B, Wang LH, Xu XF. Primary hepatic sarcomas: CT findings. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:2196-2205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Buetow PC, Buck JL, Ros PR, Goodman ZD. Malignant vascular tumors of the liver: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1994;14:153-166; quiz 167-8. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Clements D, Hubscher S, West R, Elias E, McMaster P. Epithelioid haemangioendothelioma. A case report. J Hepatol. 1986;2:441-449. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Eckstein RP, Ravich RB. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver. Report of two cases histologically mimicking veno-occlusive disease. Pathology. 1986;18:459-462. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Locker GY, Doroshow JH, Zwelling LA, Chabner BA. The clinical features of hepatic angiosarcoma: a report of four cases and a review of the English literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1979;58:48-64. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Dail DH, Liebow AA, Gmelich JT, Friedman PJ, Miyai K, Myer W, Patterson SD, Hammar SP. Intravascular, bronchiolar, and alveolar tumor of the lung (IVBAT). An analysis of twenty cases of a peculiar sclerosing endothelial tumor. Cancer. 1983;51:452-464. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Azumi N, Churg A. Intravascular and sclerosing bronchioloalveolar tumor. A pulmonary sarcoma of probable vascular origin. Am J Surg Pathol. 1981;5:587-596. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Gledhill A, Kay JM. Hepatic metastases in a case of intravascular bronchioloalveolar tumour. J Clin Pathol. 1984;37:279-282. [PubMed] |