INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic disease with recurrent uncontrolled inflammation of the colon. The rectum is always affected with inflammation spreading from the distal to the proximal colonic segments. The terminal ileum is typically not involved but some patients with extensive disease may show endoscopic signs of “backwash ileitis”. As the course of disease and extent vary considerably among patients, an individualized diagnostic and therapeutic approach is necessary.

The purpose of clinical practice guidelines is to indicate the best approaches to medical problems based on scientific findings. However, in the case of UC, if we consider just 3 different distribution patterns (proctitis, left-sided, pancolitis), 4 disease activities (remission, mild, moderate, severe), and 4 possible disease courses (asymptomatic after initial flare, increase in severity over time, chronic continuous symptoms, chronic relapsing symptoms), 48 different situations have to be evaluated before giving scientific advice. With the addition of further important factors such as the patient’s extra-intestinal manifestations, age, concomitant diseases, previous operations, medical intolerances, lifestyles and personal wishes this number exceeds a thousand possible regimes. So guidelines can only aim to indicate the preferable but not necessarily the only acceptable therapeutic approach and are meant to be used flexibly in a manner best suited to the individual patient. Therefore, the therapeutic approaches described in this article are meant to provide a general, practice-orientated overview of the important issues on UC treatment. Recommendations are based on published consensus guidelines of the national German [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Verdauungs- und Stoffwechselkrankheiten (DGVS)][1,2] and international societies [American College of Gastroenterology (ACG)[3], European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO)][4-6] as well as on the authors’ experience. Evidence levels (EL) and recommendation grades (RG) are given according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, EL 1 being the highest evidence level and RG A the strongest recommendation. ACG and DGVS guideline recommendations are graded from A (highest) to D (lowest).

The goal of medical treatment in UC is the rapid induction of a steroid-free remission and the prevention of complications of the disease itself and its treatment. In Crohn’s disease experts are currently debating the usefulness of a “top-down” strategy, giving highly potent drugs in the early stages of the disease in order to prevent complications. In contrast, guidelines on UC, a putatively curable disease (by means of colectomy), still favor a pyramidal step-up approach where 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) is considered the baseline medication, steroids and immunomodulators function to intensify the treatment, while infliximab (IFX), calcineurin inhibitors [cyclosporine A (CsA), tacrolimus] or surgery are considered as rescue therapy.

MANAGEMENT OF ACTIVE UC

Symptoms of new onset UC or recurrent flare-ups usually consist of abdominal pain, bloody and/or mucous diarrhea. Severe cases present with weight loss, tachycardia, fever, anemia and bowel distension. Before starting medical treatment other etiologies of colitis/enteritis such as infections [Clostridium difficile, cytomegalovirus (CMV)], toxic reactions (e.g. antibiotics, NSAID colitis), mesenteric ischemia or intestinal malignancies should be ruled out. Opportunistic infections (e.g. CMV infection) need to be excluded prior to medical therapy escalation, especially in patients under immunosuppressive therapy with a corticosteroid-refractory course.

Although there is no gold standard, minimal diagnostic workup for UC includes medical history, clinical evaluation (focusing on extraintestinal manifestations), full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), stool microbiology, ultrasound and endoscopy with mucosal biopsies[6]. If there is any doubt about the diagnosis in the acute setting, endoscopic and histological confirmation should be repeated after a period of time has passed (ECCO EL 5, RG D; DGVS C).

The choice of treatment depends on the degree of activity, distribution (proctitis, left-sided or extensive colitis), course of disease, frequency of relapses, extraintestinal manifestations, previous medications, side-effect profile and the patient´s individual wishes.

The degree of activity can be classified according to the Montreal classification as: Remission (S0): 3 or less stools per day without any presence of blood or increased urgency of defecation; Mild (S1): up to 4 stools per day, possibly bloody. Pulse, temperature, hemoglobin concentration and ESR are normal; Moderate (S2): 4 to 6 bloody stools daily, no signs of systemic involvement; Severe (S3): more than 6 bloody stools daily, signs of systemic involvement (temperature above 37.5°C, heart rate above 90/min, hemoglobin concentration below 10.5 g/dL, or ESR above 30 mm/h).

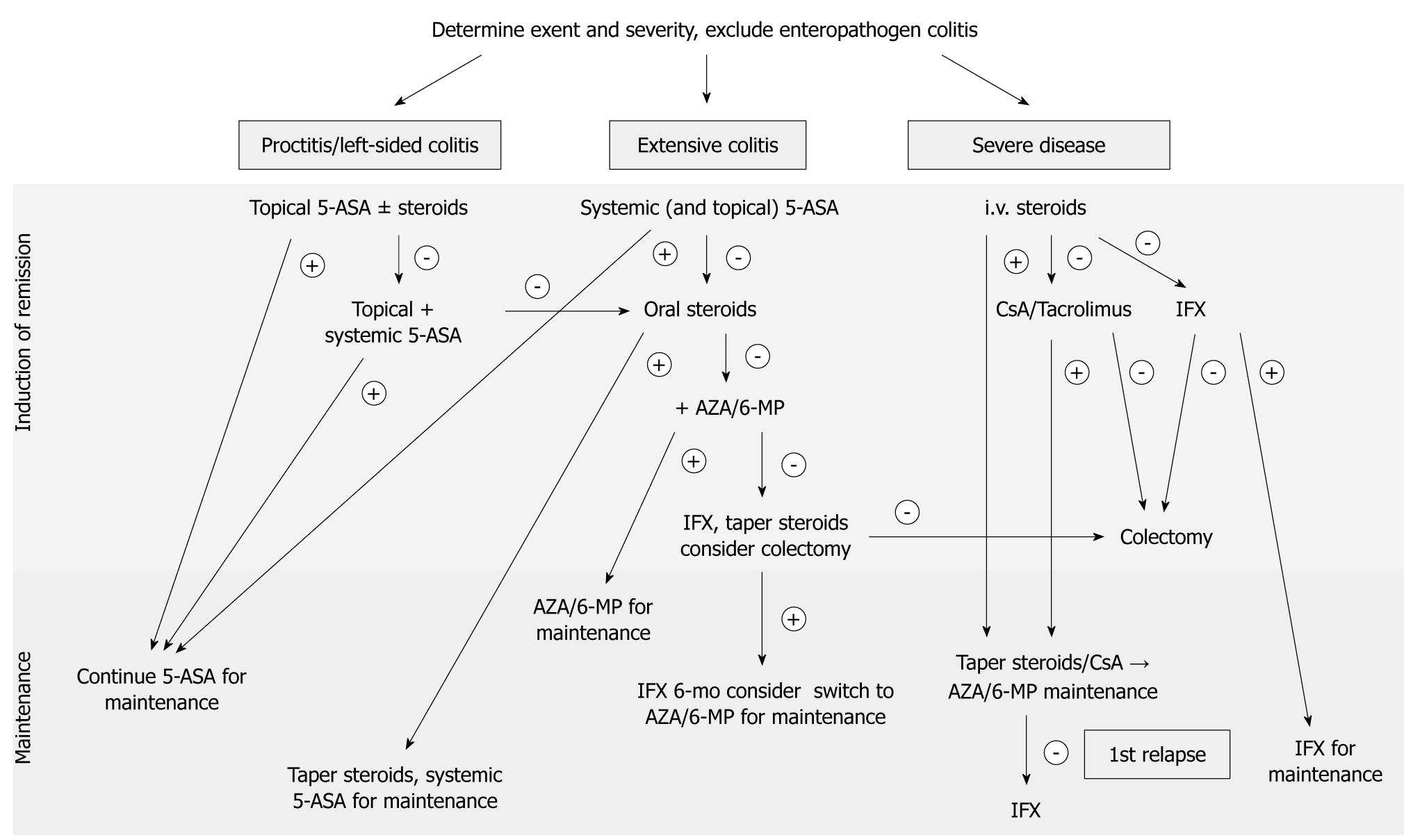

Distribution patterns depend on the part of the colon involved and are designated according to the Montreal classification as proctitis (E1), left-sided colitis (E2, limited to the sigmoid and descending colon) or extensive colitis (E3, also referred to as pancolitis). A graphical treatment algorithm is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Treatment algorithm for ulcerative colitis.

5-ASA: 5-Aminosalicylic acid; AZA: Azathioprine; CsA: Cyclosporine A; IFX: Infliximab; 6-MP: 6-Mercaptopurine.

Proctitis/distal colitis

Colitis limited to the rectum with mild or moderate activity should be initially treated topically[7]. A 5-ASA suppository (e.g. mesalazine 1 g/d) is the drug of first choice (ECCO EL 1b, RG B; DGVS EL A) and induces remission in 31-80% of patients compared to 7-11% in the placebo-treated group[8]. There is no dose response to topical therapy above 1 g mesalazine daily. 5-ASA foam enemas are an alternative, but suppositories deliver the drug more effectively to the rectum and are often better tolerated by patients due to their smaller volume[9].

Topical corticoids (budesonide 2-8 mg/d, hydrocortisone 100 mg/d) are less effective than topical mesalazine[10]. If no therapeutic effect is observed, treatment escalation using a combination of oral mesalazine (2-6 g/d for induction), together with topical mesalazine and/or a topical steroid is recommended as second-line therapy (ECCO EL 1b, RG B; DGVS A). If symptoms do not resolve within 2-4 wk, the patient’s adherence to medical treatment should be evaluated. Repeated exclusion of infectious colitis and endoscopic reconfirmation of persisting inflammatory proctitis might be helpful to guide the subsequent therapeutic approach, as an unrecognized co-existing irritable bowel syndrome or infectious colitis may be the reason for the refractory course. CMV infection is best diagnosed using immunohistochemical staining of viral proteins in mucosal biopsies, while conventional staining often gives false negative results. Quantitative CMV PCR presents the dilemma that positive results cannot distinguish between the presence of CMV as an innocent bystander in inflamed mucosa and its causative role in inflammation[11].

Confirmed persistent proctitis, in spite of combined local and topical therapy, is best treated as if it were more extensive or severe colitis.

Left-sided UC

Left-sided active UC of mild-to-moderate severity should be initially treated with topical aminosalicylates (ECCO EL1b, RG B; ACG EL A) combined with > 2 g/d oral mesalazine. Comparative trials revealed a dose-response of oral mesalazine (< 2.4 g vs 4.8 g/d) with more rapid clinical improvement and cessation of rectal bleeding in patients taking a higher dose (16 d vs 9 d, P < 0.05), but failed to show significant differences in remission rates 20.2% vs 17.7% (not significant)[12,13]. Again, treatment escalation by a combination of topical mesalazine with oral 5-ASA and/or topical steroids is possible (ECCO EL 1b, RG B). If rectal bleeding persists after 10-14 d despite combined treatment, systemic steroids should be introduced (ECCO EL 1b, RG C; DGVS EL B; ACG EL C). The steroid starting dose is 40-60 mg orally once daily. Marked differences between 40 and 60 mg starting doses have not been found (DGVS EL A)[14], and steroid regimes differ depending on country and hospital. Without proven superiority, common regimes start with

40 mg prednisolone daily for 1 wk, followed by 30 mg/d for another week and 20 mg/d for 1 mo, before decreasing the dose by 5 mg/d per week. Concerns about possible steroid side effects have led to a more restrictive introduction of steroids in the US compared with European countries and the development of promising new oral steroid formulas with mainly colonic release and low systemic bioavailability (e.g. beclomethasone diproprionate, budesonide)[15,16].

Severe left-sided colitis is usually an indication for hospital admission and systemic therapy (ECCO EL 1b, RG B).

Extensive UC

Extensive UC of mild-to-moderate severity should initially be treated with oral sulfasalazine at a dose titrated up to 4-6 g/d (ACG EL A) or a combination of oral and topical mesalazine (ECCO EL 1a, RG A; DGVS EL A). However, oral 5-ASA formulas induce remission in only approximately 20% of patients[17]. Patients who do not respond to this treatment within 10-14 d or who are already taking appropriate maintenance therapy should be treated additionally with a course of oral steroids (ECCO EL 1b, RG C; ACG EL B). In the case of steroid-dependency (ECCO EL 1a, RG A) or steroid refractory course (ECCO EL 1a, RG B, ACG A), azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg per day) or 6-mercaptopurine (1.5 mg/kg per day) should be introduced for induction of remission and remission maintenance.

Severe UC

Severe UC is defined as more than 6 bloody stools per day and signs of systemic involvement (fever, tachycardia, anemia). These patients should be hospitalized for intensive treatment and surveillance (ECCO EL 5, RG D) as the development of a toxic megacolon and perforation is a potentially life-threatening condition. Intravenous steroids (e.g. methylprednisolone 60 mg/d or hydrocortisone 400 mg/d) remain the mainstay of conventional therapy to induce remission (ECCO EL 1b, RG D; DGVS C). Patients refractory to maximal oral treatment with prednisolone and 5-ASA can be given the tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α blocker IFX at 5 mg/kg (ACG EL A).

Nevertheless, colectomy rates are as high as 29% in patients with severe UC and who need intravenous corticosteroids[18]. They should therefore be presented to the colorectal surgeon on the day of admission. It is crucial that gastroenterologists and surgeons provide joint daily care in order to avoid delaying the necessary surgical therapy. In the case of a worsening condition or a lack of amelioration after 3 d of steroid therapy, colectomy should be discussed, since extending steroid therapy beyond 7 d without clinical effect carries no benefit[18], but causes otherwise preventable postoperative wound-healing disorders[19]. The response to intravenous steroids is best assessed by stool frequency, CRP and abdominal radiography on day 3 (ECCO EL 2b, RG B). If drug therapy fails, either proctocolectomy (DGVS EL C, ACG EL B) or rescue therapy with CsA (ACG EL A) is recommended.

In order to prevent immediate surgical therapy in corticoid resistant cases calcineurin inhibitors (CsA, tacrolimus) and IFX are available as second-line therapies, as detailed below.

Continuous intravenous CsA monotherapy with 4 mg/kg per day is effective and can be an alternative for patients with contraindications for corticosteroid therapy (e.g. a history of steroid psychosis, DGVS EL A). After successful induction of remission, an immunosuppressant such as azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg per day) should soon be added, CsA switched to oral therapy with tacrolimus and tapered over a period of 3-6 mo (DGVS C). Note that it may take up to 3 mo for the therapeutic effects of azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine to develop. Neither CsA nor tacrolimus are indicated for maintenance therapy. Intravenous CsA achieves marked short-term responses in 50%-80% of patients receiving CsA as rescue therapy[20,21]. However, studies on long-term outcomes indicated that 58%-88% of these patients underwent colectomy within the following 7 years[21,22]. One major advantage of CsA over IFX in rescue therapy is its short half-life. If it proves ineffective it is cleared within a few hours, whereas IFX will circulate for weeks.

Tacrolimus is another calcineurin inhibitor given in an oral dose of 0.1-0.2 mg/kg per day or 0.01-0.02 mg/kg per day intravenously to achieve trough concentrations of 10-15 ng/mL[23]. A retrospective uncontrolled study indicated that lower trough levels of 4-8 ng/mL are also effective and are associated with fewer side effects[24].

Due to the elevated risk of opportunistic infection with Pneumocystis jiroveci, chemoprophylaxis is recommended in patients under triple immunosuppressive therapy (DGVS EL B). Possible regimes are trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 160/800 mg twice a week or, in case of intolerance, inhalation of 300 mg pentamidine once per month.

According to the ECCO and the newer ACG guidelines, IFX may be effective in the prevention of colectomy. In clinical practice it is widely considered a second choice due to its long half-life compared to CsA. Infliximab is given intravenously at a single dose of 5 mg/kg followed by scheduled infusions on weeks 2 and 6, and every 8 wk thereafter. One controlled trial on 45 patients with severe corticoid-refractory colitis compared IFX versus continued intravenous betamethasone. A significantly lower number of patients, 7/24 vs 14/21 (P = 0.017; odds ratio 4.9; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.4-17), proceeded to colectomy within 3 mo with IFX[25]. In a recent trial of infliximab IFX as rescue therapy in tacrolimus-refractory patients with active UC, about a quarter of patients (6 of 24) responded to IFX[26]. Nevertheless, effectiveness is not yet proven, as the present number of case series of infliximab IFX rescue therapy in steroid-refractory severe extended colitis is small, with wide differences concerning colectomy rates (20% to 75%)[27,28]. Patients who required IFX to induce remission should receive regular maintenance therapy with IFX for at least 6 mo. Adalimumab, a fully humanized TNF-α blocker, is not yet available for the treatment of UC.

Selective physical apheresis of activated immune cells involved in the inflammatory process of UC (leukocytapheresis) is an alternative strategy proposed for the treatment of active UC, but its role remains controversial. Although trials in Japan showed leukocytapheresis to be equal to corticoid treatment for inducing remission while displaying fewer side effects[29,30], the most recent study of an international cohort did not show significant differences in clinical outcome between the apheresis- and sham-treatment groups[31].

Only a small amount of data is available on methotrexate (MTX) for induction of remission. The only randomized placebo-controlled study did not show any effect in UC. Neither did a comparative study of 6-mercaptopurine, oral MTX or 5-ASA additional to prednisolone in 34 steroid-dependent UC patients, with remission rates of 58.3% in the MTX group compared with 35% in the 5-ASA group (P > 0.5). This disappointing effect may result from the very low doses of MTX (15 mg/kg per week) administered orally in both studies. Although existing guidelines do not generally recommended MTX, in individual cases therapy with an initial dose of 25 mg/wk followed by dose reduction to 15 mg/wk after achieving remission can be tried. Significant side effects (hepatotoxicity, bone marrow depression, MTX-induced lung injury) should be monitored and strict contraception performed (risk of teratogenicity). In order to reduce side effects 5 mg oral folic acid given on the morning after MTX administration is effective and safe[32].

Adjuvant therapeutic considerations in severe UC

Antibiotic therapy is only recommended if infection is considered (DGVS EL A). Application of metronidazole or tobramycin has not shown consistent benefit in severe UC[33-35]. Patients should be given enteral nutrition if tolerated and subileus/ileus are absent (DGVS EL B/C) since bowel rest in acute colitis did not alter the outcome and enteral nutrition was shown to be associated with significantly fewer complications (9% vs 35%)[36].

Prediction of outcome and surgical therapy

In a recent population-based European study, the global risk of colectomy in UC was 8.7% over 10 years. Efforts have been made to identify patients who are at high risk of not responding adequately to pharmacological therapy. In Crohn’s disease, factors such as young age at first diagnosis, early steroid use, ileal disease, mucosal healing, and smoking were identified as important for developing disabling disease or for major abdominal surgery[37]. Much less is known in UC. According to data from different population-based studies, including the recent 10-year data from the Norwegian IBSEN cohort, initial extensive colitis, elevated ESR (> or = 30 mm/h) and sclerosing cholangitis were associated with an increased risk of colectomy[38-40]. In contrast, older age at disease onset (> or = 50 years)[40] and smoking[41,42] reduced the risk of subsequent colectomy. In a prospective study evaluating 49 hospitalized patients with severe UC, patients treated with steroids and/or CsA, a stool frequency of > 8/d or 3-8 stools/d, and increased CRP (> 0.45 mg/L) on day 3 predicted the need for colectomy with 85% certainty[43]. Further work to identify predictive parameters of refractory courses should help to prevent a delay in inevitable surgical therapy.

Emergency indications for surgery includes refractory toxic megacolon, perforation and continuous severe colorectal bleeding (ACG EL C)[44,45]. In this situation the recommended operation is colectomy and ileostomy, leaving the rectum in situ, since reconstruction is not an option in the acute setting (ECCO EL 4, RG C).

Elective surgery is indicated in chronic continuous colitis refractory to immunosuppressive treatment, detection of dysplasia or malignancy, and stricturing disease causing partial or total intestinal obstruction. In elective surgery common surgical therapy is total proctocolectomy with ileal J-pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA). Although with IPAA a curative therapy for UC is available, high rates (up to 20%) of postoperative complications with abscesses, sepsis, fistulas[46], and postoperative impaired fertility and sexual function are unsolved problems[47,48]. Ileorectal anastomosis is a temporary alternative in selected cases (e.g. young women who have not had children), but harbors the risk of disease recurrence and/or cancer development in the remaining rectal segment[45].

MAINTENANCE OF REMISSION

Remission is clinically defined by 3 or less stools per day without any presence of blood or increased urgency of defecation. The major goal of maintenance therapy is a steroid-free remission to avoid severe and partially disabling long-term side effects of corticoid treatment. Continuing medical therapy that does not achieve this goal is therefore not recommended and should be changed (ECCO EL 5, RG D). More than half of patients with UC have a relapse in the year following a flare. In a recent population-based outcome survey conducted in Copenhagen with a cohort of 1575 patients with newly diagnosed UC, 13% had no relapse within the following 5 years, 74% had less than 5 relapses and 13% suffered an aggressive course with more than one relapse per year[49]. Maintenance treatment is therefore recommended for all patients (ECCO EL 1a, RG A), but intermittent therapy is also acceptable for a few patients with an indolent course of the disease.

First line therapy for maintenance of remission is 5-ASA administered orally or (in the case of left-sided colitis) rectally[13,50]. All the available different 5-ASA preparations are effective and no convincing data are available favoring any specific preparation. Sulfasalazine, an azo-bound combination of mesalazine and sulfapyridine, is equally or even slightly more effective. While the ACG guidelines recommend it for induction as well as remission therapy, the European guidelines reserve its use for induction and maintenance therapy in patients with additional joint manifestations due to its higher toxicity (ECCO EL 1a, RG A). First-line medical therapy for proctitis and left-sided colitis consists of topical 5-ASA with a minimum dose of 1 g 3 times a week (ECCO EL 1b, RG B; ACG EL A). Oral mesalazine can be added as second-line therapy and has been shown to be superior compared with monotherapy (ECCO EL 1b, RG B), or it can be given alone if long-term rectal treatment is not accepted by the patient. For extensive disease, oral mesalazine is the therapy of first choice. It is effective and well tolerated at doses > 800 mg/d for maintenance of remission[13], although a clear dose-response effect has yet to be established.

Compliance is a key factor in disease control and maintenance of remission. In an internet-based survey of 1595 UC patients receiving 5-ASA therapy, major reasons for poor compliance were identified as ‘too many pills’ and ‘dosing required too many times each day’[51]. In a prospective survey in Michigan only 71% of the originally prescribed medical therapy was finally taken by the patients included in the study[52]. A new generation of aminosalicylates with prolonged release formulations has been engineered over the last few decades (e.g. Eudragit-S-coated, pH-dependent mesalamine, ethylcellulose-coated mesalamine, and multimatrix-release mesalamine). All three currently available trials comparing a once versus a twice daily dose of prolonged release mesalamine for maintenance of remission in mild-to-moderate UC did show non-inferiority or even superiority of a once daily medication, in part due to increased compliance[53-55]. Once daily dosing of a prolonged release formulation could therefore be a promising approach to further reduce recurrent flares in maintenance therapy.

In case of side effects of the 5-ASA treatment with the probiotic strain Escherichia coli Nissle is an alternative for maintenance of remission with comparable efficacy (ECCO EL 1b, RG A)[56,57].

Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine are indicated as steroid-sparing agents for steroid-dependent patients or for patients not adequately sustained and with frequent relapses under aminosalicylate treatment (ECCO EL 5, RG D; ECCO EL A). The optimal dose (1.5-2.5 mg/kg per day) can be taken once daily. Therapy should be monitored by a leucocyte count of lower than 4.5 × 109/L but higher than 2.5 × 109/L. If remission is successfully induced it is recommended to continue maintenance therapy for at least 3-5 years[58,59], although there is no hard evidence on the optimal duration of treatment. Side effects such as bone marrow suppression, progressive elevation of lever enzymes, toxic pancreatitis may occur (usually within the first weeks) and require immediate termination of azathioprine treatment. A 3-fold increased risk of opportunistic infection is estimated under azathioprine therapy, especially when used in conjunction with IFX and steroids[60].

IFX is effective in maintaining improvement and remission and is therefore recommended for those patients who initially respond to the IFX induction regime (ECCO EL 1b, RG A)[61]. The standard IFX dose is 5 mg/kg. Higher initial treatment doses have not been shown to be of any benefit. As shown for Crohn’s disease, 25%-40% of patients with initial response to IFX develop loss of response and benefit from dose escalation to 10 mg/kg or shortening dosing intervals during further therapy[62,63].

For maintenance therapy, scheduled intravenous administration every 8 wk has been proven to be more effective and safer than periodic application, probably due to a reduced formation of antibodies (ABs) against anti-TNF agents[64,65]. Most infusion reactions are mild-to-moderate and consist of flushing, headaches, dizziness, chest pain, dyspnea, fever or pruritus. Halting or lowering the infusion rate often provides relief. In order to prevent adverse reactions and AB formation, premedication with steroids prior to IFX administration is recommended (ECCO EL 2, RG C)[66]. Serious infection occurred in approximately 3% of patients treated with IFX in the ACT 1 and ACT 2 trials[61]. Although the information available from meta-analyses, from IFX safety registries in Crohn’s disease, and from IFX therapy in rheumatoid arthritis differ widely, a 3-fold higher rate of opportunistic infectious under IFX therapy is estimated[67-70]. In order to prevent reactivation of latent infection, exclusion of latent tuberculosis and hepatitis B should be performed by chest radiography, serologic testing, skin test and/or lymphocyte stimulation test (QuantiFERON-TB Gold®).

There is no existing recommendation on the duration of IFX treatment in stable remission. In stable long-term remission, interruption of IFX treatment while continuing 5-ASA or switching maintenance therapy to azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine are possible de-escalation approaches.

MTX for maintenance therapy can be considered in individual cases, especially when other immunosuppressants are not tolerated. Furthermore, patients with refractory arthropathy may benefit. Because the available data are restricted to one randomized prospective study[71] and several retrospective series with a total of only 91 patients[72-74], no consensus recommendation for MTX in UC is given[6].

ALTERNATIVE AND FUTURE TREATMENTS

Several alternative therapies have emerged for the treatment of UC. Ova of the non-pathogenic helminth trichiuris suis taken orally has shown initial success in a double-blind placebo-controlled trial, inducing remission in 43% of patients taking ova compared with 16.7% in the placebo group[75]. Transdermal administration of nicotine was proposed as being effective in active UC. A systematic review and analysis of 5 relevant studies demonstrated its effectiveness in achieving remission compared with placebo. However, direct comparative trials with 5-ASA are still missing. Omega-3 fatty acids, which are largely present in fish oil, have shown anti-inflammatory properties by reducing the production of leukotriene B4[76]. However, in a meta-analysis of the 3 available studies on 138 UC patients in remission, no evidence was found to support the use of omega-3 fatty acids for maintenance of remission as similar relapse rates were found in the study group and the placebo group (relative risk, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.51-2.03; P = 0.96)[77]. Taken together, due to a lack of data on efficacy, safety and adverse events, no recommendation is given for the therapies mentioned above.

Advances in the field of biological therapy focus on novel target molecules and alternative means of administration, some of which have already been approved for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Further TNF-α AB preparations include certolizumab, etanercept and adalimumab - approval of the latter for the treatment of UC could be expected this year. Other biologicals such as natalizumab (anti-α4-integrin AB), visilizumab (anti-CD3 receptor AB), fontolizumab (anti-interferon gamma AB), alicaforsen (anti-sense oligonucleotide to human ICAM1), basiliximab (IL-2 receptor AB), anti-IL12 ABs and anti-IL-6 ABs have in part been tested in acute steroid-refractory UC but data on maintenance of remission are not available as yet.