Published online Jan 14, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i2.226

Revised: September 29, 2010

Accepted: October 6, 2010

Published online: January 14, 2011

AIM: To investigate the relationship between low-dose aspirin-induced small bowel mucosal damage and blood flow, and the effect of rebamipide.

METHODS: Ten healthy volunteers were enrolled in this study. The subjects were divided into two groups: a placebo group given low-dose aspirin plus placebo and a rebamipide group given low-dose aspirin plus rebamipide for a period of 14 d. Capsule endoscopy and contrast-enhanced ultrasonography were performed before and after administration of drugs. Areas under the curves and peak value of time-intensity curve were calculated.

RESULTS: Absolute differences in areas under the curves were -1102.5 (95% CI: -1980.3 to -224.7, P = 0.0194) in the placebo group and -152.7 (95% CI: -1604.2 to 641.6, P = 0.8172) in the rebamipide group. Peak values of time intensity curves were -148.0 (95% CI: -269.4 to -26.2, P = 0.0225) in the placebo group and 28.3 (95% CI: -269.0 to 325.6, P = 0.8343) in the rebamipide group. Capsule endoscopy showed mucosal breaks only in the placebo group.

CONCLUSION: Short-term administration of low-dose aspirin is associated with small bowel injuries and blood flow.

- Citation: Nishida U, Kato M, Nishida M, Kamada G, Yoshida T, Ono S, Shimizu Y, Asaka M. Evaluation of small bowel blood flow in healthy subjects receiving low-dose aspirin. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(2): 226-230

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i2/226.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i2.226

There have been several reports recently on the incidence of small bowel complications induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)[1,2]. However, there have been few investigations of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (ASA)-induced small bowel damage. Endo et al[3] reported that small bowel pathology was observed in 80% of 10 healthy subjects after 2 wk with low-dose ASA but that there was no significant difference in mucosal break in subjects who used low-dose ASA and those who did not (with ASA: 30%, without: 0%). Smecuol et al[4] reported that 3 cases of erosion and 1 case of bleeding were observed in 4 of 20 healthy subjects, and these cases were thought to have been caused by increase in permeation of the small intestinal mucosa (increased sucrose urinary excretion: 107.0 mg; range, 22.9-411.3, P < 0.05). These results indicated that mucosal breaks caused by taking low-dose ASA occurred not only in the upper gastrointestinal tract (GI) but also in the lower GI tract. However, the cause of small bowel injury is not clear.

Bjarnason et al[5] reported that NSAIDs-induced small intestinal damage is caused by a lack of mucosal prostaglandins, decrease in blood flow, induction of nitric oxide and increased permeability. There are several key words for this hypothesis and we should investigate them, such as permeability, blood flow, free radicals, nitric oxide, and inflammation.

There are various techniques for measurement of blood flow in organs. Nishida et al[6] reported that measurement of liver blood flow by using contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CE-US) was useful for diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma, and there have been some reports on evaluation of gastric blood flow using CE-US[7,8].

We focused on blood flow in the small bowel as a possible cause of ASA-derived small bowel complications. There is no therapeutic strategy for the prevention of these complications. We wanted to investigate a candidate drug. Rebamipide is an anti-ulcer drug[9]. Its actions include increasing endogenous prostaglandin[10], scavenging free radicals, suppressing permeability, and elevating blood flow in the stomach[11]. In this study, we investigated the relationship between low-dose ASA-induced small bowel mucosal damage and small bowel blood flow, and we also evaluated the preventive effect of rebamipide against small bowel damage and the effect of rebamipide on blood flow.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hokkaido University Hospital. Written informed consent was given by all participants.

Inclusion criteria were absence of upper and lower GI injuries, such as erosion, ulcer, and bleeding on endoscopy. The subjects enrolled in this study were aged from 20 to 50 years. Subjects who were taking some drugs were excluded.

All of the participants in this study were healthy. A randomized, double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled trial using rebamipide was performed.

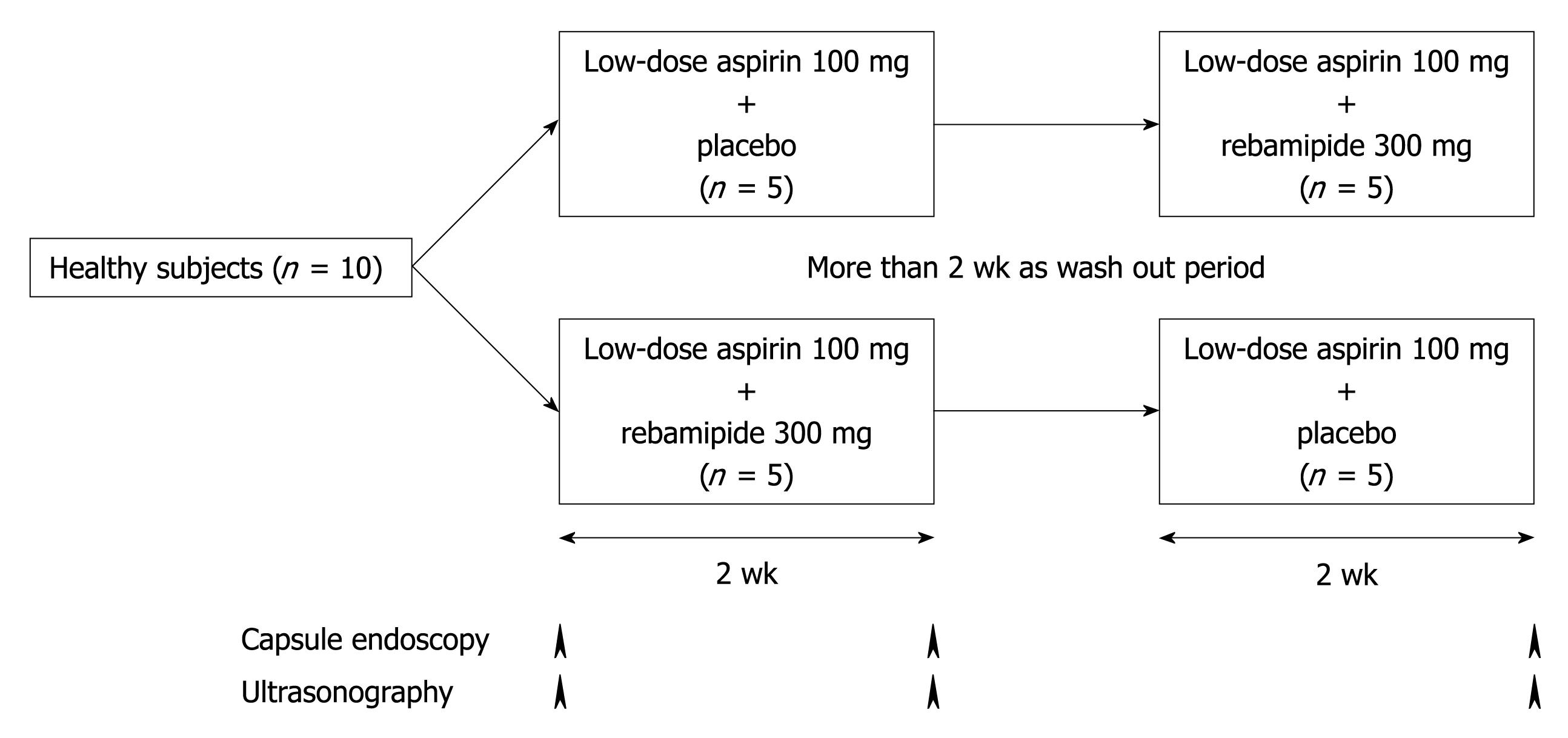

The study design is shown in Figure 1. The subjects were divided into two groups: a placebo group with low-dose ASA (100 mg once daily) plus placebo (three times daily) and a rebamipide group with low-dose ASA (100 mg once daily) plus rebamipide (100 mg three times daily). The first period lasted 14 d. After a wash-out period of more than 14 d and the second period lasted a further 14 d. All subjects underwent capsule endoscopies and CE-US before and after each administration period.

The placebo was prepared by Yamanami Pharmacy. Rebamipide (100 mg) and the placebo were each contained in a soft colored capsule.

Subjects were recruited for the treatment sequences in a random fashion according to a randomization schedule for the treatment period. A randomization number that was associated with a specific treatment, either rebamipide or placebo, was assigned to each subject. Randomized numbers were generated by the SAS program.

We used the Given video capsule system (PillCam®, Given Imaging Ltd., Yoqneam, Israel) in this study. The capsule endoscopy procedure and methodology for the review of images were conducted as previously described. All video images were analyzed by skilled reviewers (Nishida U and Kato M) who remained blinded to the subjects’ treatment protocol. All images were saved for final comprehensive analysis upon completion of post-treatment capsule endoscopies.

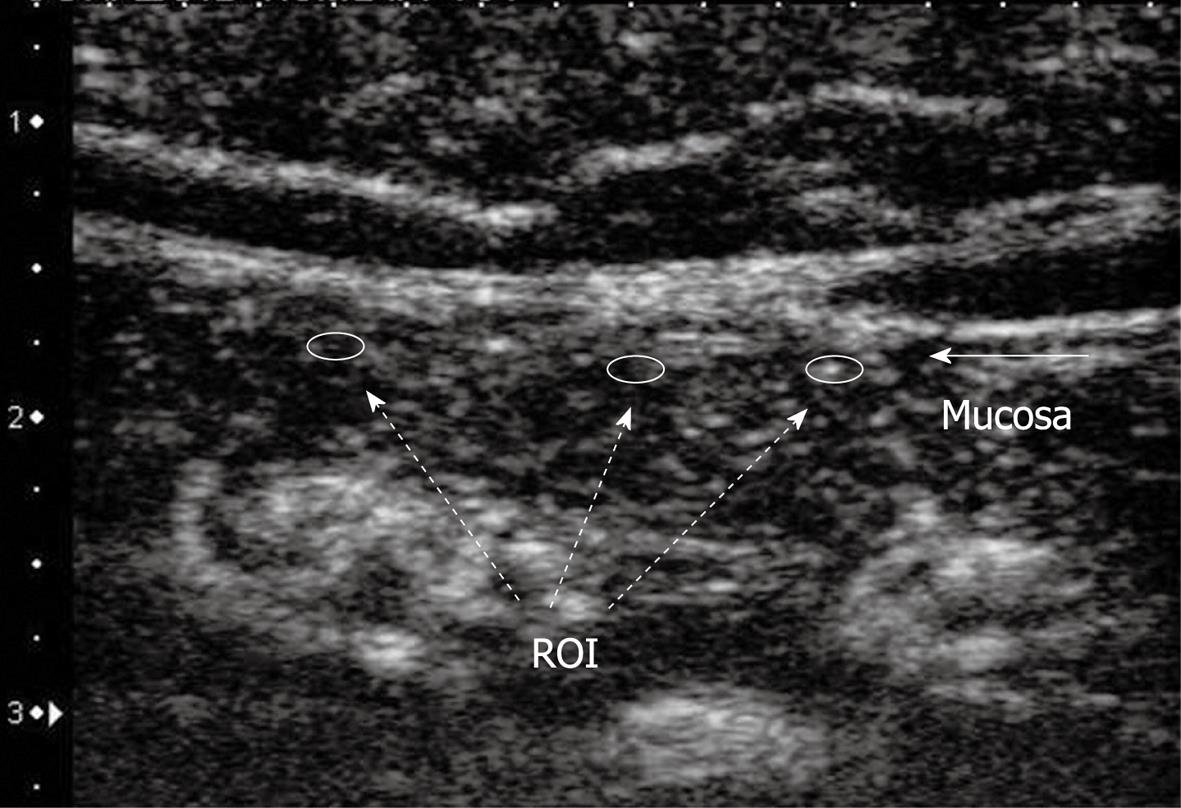

The longitudinal view of the small bowel was imaged in the left upper abdomen. Baseline CE-US and contrast-enhanced CE-US were performed with a 7.5 MHz center frequency linear transducer using an ultrasound unit SSA-790A (AplioXG™, Toshiba Medical Systems Co., Otawara, Japan). The imaging mode was pulse subtraction. Prior to CE-US, 20 mg of scopolamine butylbromide was injected intravenously to suppress peristalsis. Perflubutane microbubbles (Sonazoid; GE Healthcare), a lyophilized preparation reconstituted for injection, were injected intravenously at a concentration of 0.015 mL/kg. Ten seconds after contrast medium injection, enhanced signals from blood flow in the small intestinal wall were captured until 45 s on cine clips equipped with the ultrasound unit. Regions of interests of fixed sizes were placed in the mucosal area of the small bowel at three regions (Figure 2). A time intensity curve (TIC) of blood flow enhancement signal in the small bowel was plotted from recorded ultrasonographic images using ImageLab software, which was developed by C++ software dedicated to CE-US images obtained by AplioXG. Area under the curve (AUC) and TIC peak value (maximum intensity) were calculated from the TIC. These values were used to estimate small bowel blood flow inside the mucosal layer.

The primary end point was evaluation of the change of low-dose ASA-induced small bowel blood flow. Blood flow was measured by CE-US. TIC for blood flow in the small bowel was plotted from recorded CE-US images with Image Lab software. The secondary end point was evaluation of the preventive effect of rebamipide with low-dose ASA-related small bowel damages such as erosion, erythema, and petechiae.

In this study, a mucosal break of the small bowel was defined as erosion, ulcer, bleeding or perforation.

Symptoms and other adverse events were recorded through this study period. If these events occurred, they were treated appropriately.

The primary end point was to evaluate changes in small bowel blood flow. Blood flow was estimated by AUC and TIC. They were analyzed by absolute differences between before and after each administration periods. They were evaluated by 95% confidential intervals. The secondary end point was to evaluate the preventive effect of rebamipide. Preventive effect was evaluated using small bowel mucosal injuries and subject numbers that got mucosal breaks. Small bowel injuries (ulcer, erosion and erythema) were described by mean ± SD. They were analyzed by Fischer’s exact test. Findings of P < 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS® version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Ten males were enrolled in this study. The mean age of the subjects was 29 ± 5 years. Two subjects were infected with Helicobacter pylori.

The values of AUC in the placebo group and rebamipide group were 464.2 ± 381.8 and 1414.1 ± 1340.3, respectively. The absolute difference is shown in Table 1. In the placebo group, there was a significant difference in the values of AUC before and after taking ASA (difference: -1102.5, 95% CI: -1980.3 to -224.7, P = 0.0194). The difference in the rebamipide group, -152.7, was not statistically significant (95% CI: -1604.2 to 641.6, P = 0.8172).

| Placebo | Rebamipide | |||||

| A.D. | 95% CI | P-value | A.D. | 95% CI | P-value | |

| AUC | -1102.5 | -1980.3 to -224.7 | 0.0194 | -152.7 | -1604.2-641.6 | 0.8172 |

| TIC | -148.0 | -269.4 to -26.2 | 0.0225 | 28.3 | -269.0-325.6 | 0.8343 |

Peak values of the TIC in the placebo group and the rebamipide group were 226.2 ± 251.4 and 402.5 ± 283.9, respectively. In the placebo group, the difference in the peak values of TIC before and after taking ASA was -148.0 (95% CI: -269.4 to -26.2, P = 0.0225), which was statistically significant. The difference in the rebamipide group, 28.3, was not statistically significant (95% CI: -269.0 to 325.6, P = 0.8343). The differences are shown in Table 1.

Changes in the numbers of erosions, petechiae and erythemas are shown in Table 2. Differences in the numbers of erosions, petechiae and erythemas in the placebo group were 0.5 ± 1.0, 10.1 ± 53.6 and -1.0 ± 2.3, respectively, and those in the rebamipide group were 0.0 ± 0.0, -8.6 ± 15.4 and -0.6 ± 1.0, respectively.

| Placebo | Rebamipide | |

| Erosion | 0.5 ± 2.7 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| Petechiae | 10.1 ± 53.6 | -8.6 ± 15.4 |

| Erythema | -1.0 ± 2.3 | -0.6 ± 1.0 |

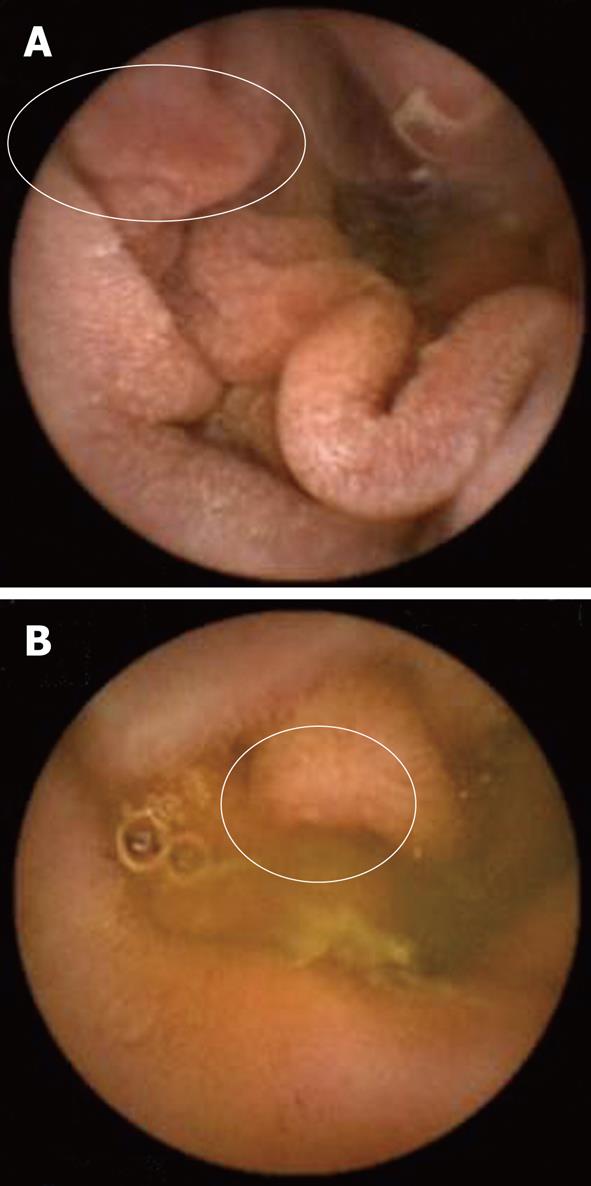

No ulcer, bleeding or perforation was observed. There were 2 cases of mucosal break in the placebo group but no cases in the rebamipide group (Table 3). Two cases of erosions were localized in the ileum region (Figure 3).

| Placebo | Rebamipide | |

| Mucosal breaks | 2 | 0 |

No adverse events were observed throughout the study period.

In the present study, treatment with low-dose ASA resulted in a decrease in small bowel blood flow, with changes in AUC of -1102.5 (95% CI: -1980.3 to -224.7, P = 0.0194) and peak value of TIC of -148.0 (95% CI: -269.4 to -26.2, P = 0.0225) (Table 1). Low-dose ASA also caused small bowel damage. Treatment with ASA induced small bowel erosion in 2 cases and increased petechiae (Tables 2 and 3). These results indicated that low-dose ASA-induced small bowel injury is correlated with decreasing small bowel blood flow. Bjarnason et al[5] proposed a cascade as the mechanism of NSAIDs-induced small bowel injury: NSAIDs induce a decrease in prostaglandin, the decrease in prostaglandin leads to a decrease in small bowel blood flow, and the decrease in small bowel blood flow leads to an increase in small bowel inflammation and injury. In another pathway, increasing permeability also leads to small bowel injury. Our results support their hypothesis; blood flow was one of the mechanisms of NSAIDs-related small bowel injury. However, small bowel damage was slight in our subjects. This might be due to the short-term use of ASA and the fact that the subjects were young and healthy. Moreover, most patients who take low-dose ASA are chronic users, and decrease in small bowel blood flow may continue for a long time. Therefore, long-term observation of small bowel blood flow is needed.

On the other hand, low-dose ASA-induced small bowel erosions in the placebo group and the rebamipide group were 20% and 0%, respectively.

Small bowel blood flow did not decrease in the rebamipide group; changes in the AUC and TIC were -152.7 and 28.3 (not statistically significant). Kim et al[11] reported that rebamipide did not decrease upper GI blood flow compared with placebo in healthy subjects taking ibuprofen. Our results suggested that rebamipide prevents a decrease in lower GI blood flow as well as a decrease in upper GI blood flow.

Recently, there have been three reports on the usefulness of drugs for low-dose ASA and NSAIDs-induced small bowel complications. Fujimori et al[12] reported that misoprostol, a prostaglandin analogue, prevented diclofenac-induced small bowel complications in healthy subjects. Niwa et al[13] reported that rebamipide prevented diclofenac-induced small bowel injury in healthy subjects. Shiotani et al[14] reported that geranylgeranylacetone (GGA: Teprenone) did not prevent low-dose ASA-induced small bowel damage. These drugs are cytoprotective drugs for gastric ulcer and gastritis. A proton pump inhibitor is useful for upper GI tract. However, it is not effective for the lower GI tract because of a lack of acid secretion. Further investigation is therefore needed to establish a novel therapeutic strategy for chemical-induced lower GI complications. These three reports may suggest that tentative drug for small bowel is needed to have the action for increasing prostaglandin as mechanism.

The number of subjects in our study was small. A study using a larger number of subjects is needed. Recently several mechanisms of ASA-induced small bowel complications were treated. But we explained only blood flow one of these several mechanisms. As the future study, we will need to examine relationship among several actions and functions.

In conclusion, low-dose ASA-induced decrease in small bowel blood flow is correlated with small-bowel mucosal injury. Rebamipide does not decrease small bowel blood flow.

Low-dose aspirin has been widely used for prevention of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. Several studies have shown that mucosal breaks caused by taking low-dose aspirin occurred not only in the upper gastrointestinal tract but also in the lower gastrointestinal tract.

However the cause of small bowel injury is not clear. One of the mechanisms of drug-induced small bowel damage is decrease in blood flow. In this study, the authors investigated the relationship between low-dose aspirin-induced small bowel mucosal damage and blood flow using video capsule endoscopy and contrast-enhanced ultrasonography, and the authors also evaluated the effect of rebamipide on blood flow.

Recent reports have highlighted the mechanisms of aspirin-induced small bowel damage, and the prevention and treatment of aspirin-induced small bowel damage. This is the first study to report that short-term administration of low-dose aspirin is associated with small bowel injuries and blood flow. And rebamipide does not decrease small bowel blood flow.

This study may represent a future strategy for therapeutic intervention in the treatment of patients with low-dose aspirin-induced small bowel mucosal damage.

Rebamipide is an anti-ulcer drug. Its actions include for increasing endogenous prostaglandin, scavenging free radicals, suppressing permeability, and elevating blood flow in the stomach. In this study contrast-enhanced ultrasonography were performed with a 7.5 MHz center frequency linear transducer using an ultrasound unit SSA-790A. The imaging mode was pulse subtraction.

This study focuses on the evaluation of small bowel blood flow in healthy subjects with low-dose aspirin (a randomized placebo-controlled double-blinded cross-over study using video capsule endoscopy and contrast-enhanced ultrasonography). Low-dose acetylsalicylic acid-induced decrease in small bowel blood flow is correlated with small-bowel mucosal injury. The collected experiences are interesting and may represent a future strategy for treatment of patients with drug-induced small bowel mucosal damage.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Uday C Ghoshal, MD, DNB, DM, FACG, Additional Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Science, Lucknow 226014, India

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Graham DY, Opekun AR, Willingham FF, Qureshi WA. Visible small-intestinal mucosal injury in chronic NSAID users. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:55-59. |

| 2. | Goldstein JL, Eisen GM, Lewis B, Gralnek IM, Aisenberg J, Bhadra P, Berger MF. Small bowel mucosal injury is reduced in healthy subjects treated with celecoxib compared with ibuprofen plus omeprazole, as assessed by video capsule endoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1211-1222. |

| 3. | Endo H, Hosono K, Inamori M, Kato S, Nozaki Y, Yoneda K, Akiyama T, Fujita K, Takahashi H, Yoneda M. Incidence of small bowel injury induced by low-dose aspirin: a crossover study using capsule endoscopy in healthy volunteers. Digestion. 2009;79:44-51. |

| 4. | Smecuol E, Pinto Sanchez MI, Suarez A, Argonz JE, Sugai E, Vazquez H, Litwin N, Piazuelo E, Meddings JB, Bai JC. Low-dose aspirin affects the small bowel mucosa: results of a pilot study with a multidimensional assessment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:524-529. |

| 5. | Bjarnason I, Thjodleifsson B. Gastrointestinal toxicity of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: the effect of nimesulide compared with naproxen on the human gastrointestinal tract. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999;38 Suppl 1:24-32. |

| 6. | Nishida M, Koito K, Hirokawa N, Hori M, Satoh T, Hareyama M. Does contrast-enhanced ultrasound reveal tumor angiogenesis in pancreatic ductal carcinoma? A prospective study. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2009;35:175-185. |

| 7. | Mitsuoka Y, Hata J, Haruma K, Manabe N, Tanaka S, Chayama K. New method of evaluating gastric mucosal blood flow by ultrasound. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:513-518. |

| 8. | Nishizawa T, Suzuki H, Masaoka T, Iwasaki E, Hibi T. Reduced conscious blood flow in the stomach during non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs administration assessed by flash echo imaging. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:1040-1044. |

| 9. | Yamasaki K, Ishiyama H, Imaizumi T, Kanbe T, Yabuuchi Y. Effect of OPC-12759, a novel antiulcer agent, on chronic and acute experimental gastric ulcer, and gastric secretion in rats. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1989;49:441-448. |

| 10. | Arakawa T, Watanabe T, Fukuda T, Yamasaki K, Kobayashi K. Rebamipide, novel prostaglandin-inducer accelerates healing and reduces relapse of acetic acid-induced rat gastric ulcer. Comparison with cimetidine. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:2469-2472. |

| 11. | Kim HK, Kim JI, Kim JK, Han JY, Park SH, Choi KY, Chung IS. Preventive effects of rebamipide on NSAID-induced gastric mucosal injury and reduction of gastric mucosal blood flow in healthy volunteers. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1776-1782. |

| 12. | Fujimori S, Seo T, Gudis K, Ehara A, Kobayashi T, Mitsui K, Yonezawa M, Tanaka S, Tatsuguchi A, Sakamoto C. Prevention of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced small-intestinal injury by prostaglandin: a pilot randomized controlled trial evaluated by capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1339-1346. |

| 13. | Niwa Y, Nakamura M, Ohmiya N, Maeda O, Ando T, Itoh A, Hirooka Y, Goto H. Efficacy of rebamipide for diclofenac-induced small-intestinal mucosal injuries in healthy subjects: a prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:270-276. |

| 14. | Shiotani A, Haruma K, Nishi R, Fujita M, Kamada T, Honda K, Kusunoki H, Hata J, Graham DY. Randomized, double-blind, pilot study of geranylgeranylacetone versus placebo in patients taking low-dose enteric-coated aspirin. Low-dose aspirin-induced small bowel damage. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:292-298. |