Published online Jan 28, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i4.484

Revised: November 25, 2009

Accepted: December 2, 2009

Published online: January 28, 2010

AIM: To test the hypothesis that the shape and length of Barrett’s epithelium are associated with prevalence of erosive esophagitis.

METHODS: A total study population comprised 869 patients who underwent endoscopy during a health checkup at our hospital. The presence and extent of Barrett’s epithelium were diagnosed based on the Prague C & M Criteria. We originally classified cases of Barrett’s epithelium into two types based on its shape, namely, flame-like and lotus-like Barrett’s epithelium, and into two groups based on its length, its C extent < 2 cm, and ≥ 2 cm. Correlation of shape and length of Barrett’s epithelium with erosive esophagitis was examined.

RESULTS: Barrett’s epithelium was diagnosed in 374 cases (43%). Most of these were diagnosed as short-segment Barrett’s epithelium. The prevalence of erosive esophagitis was significantly higher in subjects with flame-like than lotus-like Barrett’s epithelium, and in those with a C extent of ≥ 2 cm than < 2 cm.

CONCLUSION: Flame-like rather than lotus-like Barrett’s epithelium, and Barrett’s epithelium with a longer segment were more strongly associated with erosive esophagitis.

- Citation: Akiyama T, Inamori M, Iida H, Endo H, Hosono K, Sakamoto Y, Fujita K, Yoneda M, Takahashi H, Koide T, Tokoro C, Goto A, Abe Y, Shimamura T, Kobayashi N, Kubota K, Saito S, Nakajima A. Shape of Barrett’s epithelium is associated with prevalence of erosive esophagitis. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(4): 484-489

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i4/484.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i4.484

In patients with Barrett’s epithelium, the resulting replacement of normal squamous epithelium with columnar epithelium can be seen in the distal esophagus as a salmon-pink-colored area that is readily visible during endoscopic examination. Barrett’s epithelium is recognized as a complication of erosive esophagitis and is the pre-malignant condition for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus[1,2]. The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma is rapidly increasing in the United States and Europe[3-5], and is reported to account for up to 50% of esophageal cancers seen in white males in the United States[5]. For esophageal carcinoma in Japan, however, the ratio of adenocarcinoma to squamous cell carcinoma is low, and no significant changes have been identified[6]. As the prevalence of erosive esophagitis is increasing, further observation of Barrett’s epithelium and esophageal adenocarcinoma is required in Japan. However, the reasoning behind the recommendation for regular endoscopic screening and biopsies in patients with Barrett’s epithelium in Japan is unclear, and whether all patients with Barrett’ epithelium, or only a subgroup with risk factors for the development of adenocarcinoma should be screened, remains controversial.

It has been known for more than a century that chronic inflammation can contribute to cancer formation. Chronic inflammatory conditions of the gastrointestinal tract, such as ulcerative colitis and chronic pancreatitis, are well known to predispose patients to carcinogenesis. Lassen et al[7] have reported that the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma was fivefold greater among patients with diagnosed esophagitis, but most of these cancers seemed to be related to Barrett’s esophagus. Several studies have indicated that a dose-response relationship exists between the severity of erosive esophagitis and the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma[8-11]. These findings suggest that the major risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma is the existence of Barrett’s epithelium complicated with erosive esophagitis.

We hypothesized that some macroscopic features of Barrett’s epithelium might be useful for identifying a subgroup with a high risk for the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective cohort study to examine the correlation of the shape and length of Barrett’s epithelium with erosive esophagitis.

A total of 869 patients (463 men, 406 women; median age, 66 years; age range, 29-91 years) who had undergone an upper endoscopy at the Gastroenterology Division of Yokohama City University Hospital between August 2005 and July 2006 were enrolled in the study. The total study population consisted of consecutive patients who had undergone endoscopy for a health checkup in our hospital. The majority of the patients were outpatients. None of the patients had previously undergone an upper digestive tract operation. Ten patients were excluded, because their profiles were unsatisfactory or they refused to participate in the present study.

At the Yokohama City University Hospital, when endoscopically examining and photographing the esophageal mucosa, the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) is always prospectively photographed. Our hospital operates a digital filing system for endoscopic images. All digital endoscopic images were independently and retrospectively reviewed by two trained endoscopists to investigate the endoscopic findings, including gastric mucosal atrophy (GMA), hiatal hernia, erosive esophagitis, and Barrett’s epithelium. If there was any inconsistency in the assessment of the digital endoscopic images, a final diagnosis was decided upon by a joint review of the digital endoscopic images.

The presence and extent of Barrett’s epithelium were diagnosed based on the Prague C & M Criteria[12]. According to these criteria, Barrett’s epithelium is defined as the macroscopic identification, using a standard endoscopy examination, of abnormal columnar esophageal epithelium suggestive of columnar-lined distal esophagus. The length of Barrett’s epithelium is measured (in cm) using the circumferential extent (the C extent) and the maximum extent (the M extent) above the GEJ, which is identified as the proximal margin of the gastric mucosal folds in centimeters[12].

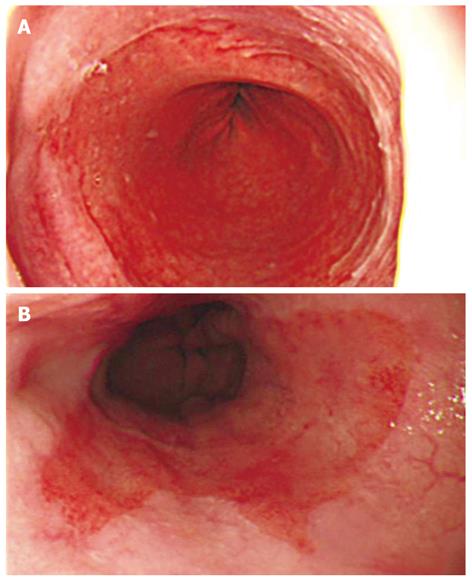

We originally classified Barrett’s epithelium into two types based on its shape. As shown in the Figure 1, we classified the shape of Barrett’s epithelium as follows: (A) the L type, in which the difference between the C extent and M extent was < 2 cm and the visible red columnar epithelium could be observed as a lotus-like shape; and (B) the F type, in which the difference was ≥ 2 cm and the columnar epithelium of Barrett’s epithelium was observed as a flame-like shape.

We further classified Barrett’s epithelium into two groups based on its length as follows: (1) Barrett’s epithelium < 2 cm, defined as a C extent of < 2 cm in length; and (2) Barrett’s epithelium ≥ 2 cm, defined as a C extent of ≥ 2 cm.

Erosive esophagitis was diagnosed based on the Los Angeles (LA) Classification[13] and was divided into three groups: none, mild (grades A and B), or severe (grades C and D).

Hiatal hernia was diagnosed when the distance between the GEJ and the diaphragmatic hiatus was ≥ 2 cm.

The atrophic area of the stomach that can be visualized endoscopically is known to extend from the antrum to the body. Previously, Kimura and Takemoto endoscopically divided GMA into six groups (C1, C2, C3, O1, O2, and O3; C, closed; O, open)[14]. GMA has been shown to progress from C1 to O3 successively, and this classification correlates well with the histological features of GMA[14]. Gastric acid secretion in patients with open-type GMA has been reported to be lower than that in patients with closed-type GMA[15]. In the present study, we defined closed-type (C1-C3) cases as mild GMA and open-type (O1-O3) cases as severe GMA.

Complete patient information, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), regular drinking habit and smoking habit, at the time of the initial diagnosis was obtained from the patient’s medical records.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Yokohama City University Hospital. The patients gave their signed informed consent to be involved in the study.

In our cohort study, to investigate the correlation between the shape and length of Barrett’s epithelium and erosive esophagitis, the variables were compared between patients with different shapes and between patients with different lengths. The statistical analysis included a χ2 test or a Fisher exact test to compare percentages, and a Mann-Whitney U test to compare continuous data. The level of significance was defined as P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using Stat View software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

The baseline characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. A total of 374 patients (43.0%) (211 men and 163 women; mean age, 68 years; range, 31-91 years) were diagnosed as having Barrett’s epithelium based on the Prague C & M Criteria[10]. These consisted of 370 cases (42.6%) with short-segment Barrett’s esophagus (SSBE), whose C extent was < 3 cm, and four cases (0.5%) with long-segment Barrett’s esophagus (LSBE), whose C extent was ≥ 3 cm. A total of 165 cases (19.0%) had erosive esophagitis: 152 (17.5%) had mild esophagitis (LA grades A and B), and 13 (1.5%) had severe esophagitis (LA grades C and D).

| Clinical characteristics | n (%) |

| Total patients | 869 |

| Patient profiles | |

| Age | |

| median; range (yr) | 66; 29-91 |

| Sex | |

| Female (%) | 406 (46.7) |

| BMI | |

| median; range | 22.2; 13.5-41.2 |

| Regular drinking habit (%) | 316 (36.4) |

| Smoking habit (%) | 319 (36.7) |

| Endoscopic results | |

| Hiatal hernia (%) | 266 (30.6) |

| GMA | |

| Open type (%) | 466 (53.6) |

| Erosive esophagitis | |

| Total (%) | 165 (19.0) |

| Mild (LA class A, B) (%) | 152 (17.5) |

| Severe (LA class C, D) (%) | 13 (1.5) |

| Barrett’s epithelium | |

| Total (%) | 374 (43.0) |

| SSBE (%) | 370 (42.6) |

| LSBE (%) | 4 (0.5) |

Table 2 shows the clinical characteristics of the subjects according to the two types of Barrett’s epithelium shape. No significant differences in age, sex, BMI, and hiatal hernia were observed between the subjects with F type and L type Barrett’s epithelium. The subjects with F type Barrett’s epithelium tended to have higher prevalence of regular drinking and smoking compared with those with L type Barrett’s epithelium, but without statistical significance. The prevalence of open-type GMA was significantly lower in the subjects with F type than L type Barrett’s epithelium. The prevalence of erosive esophagitis, especially severe esophagitis, was significantly higher in the subjects with F type than L type Barrett’s epithelium.

| Shape of Barrett’s epithelium | P value | ||

| L type (n = 353) | F type (n = 21) | ||

| Age | |||

| Median; range (yr) | 68; 31-91 | 68; 54-80 | 0.8532 |

| Sex | |||

| Female (%) | 154 (43.6) | 9 (42.9) | 0.94501 |

| BMI | |||

| Median; range | 22.5; 14.4-41.2 | 22.0; 18.1-30.5 | 0.8565 |

| Regular drinking habit (%) | 144 (40.8) | 13 (61.9) | 0.05681 |

| Smoking habit (%) | 160 (45.3) | 14 (66.7) | 0.05681 |

| Hiatal hernia (%) | 145 (41.1) | 8 (38.1) | 0.96692 |

| GMA | |||

| Open type (%) | 184 (52.1) | 5 (23.8) | 0.02162 |

| Erosive esophagitis (%) | |||

| Total | 112 (31.7) | 13 (61.9) | 0.00441 |

| Mild | 103 (29.2) | 9 (42.9) | 0.27872 |

| Severe | 9 (2.5) | 4 (19.0) | 0.00073 |

Table 3 shows the clinical characteristics broken down by the two lengths of Barrett’s epithelium. The prevalence of hiatal hernia and erosive esophagitis was significantly higher in subjects with Barrett’s epithelium with a C extent of ≥ 2 cm.

| The C extent of Barrett’s epithelium | P value | ||

| < 2 cm (n = 347) | ≥ 2 cm (n = 27) | ||

| Age | |||

| Median; range (yr) | 68; 31–91 | 70; 42–86 | 0.4933 |

| Sex | |||

| Female (%) | 149 (42.9) | 14 (51.9) | 0.36831 |

| BMI | |||

| Median; range | 22.5; 14.4–41.2 | 22.3; 16.9–28.2 | 0.7199 |

| Regular drinking habit (%) | 143 (41.2) | 14 (51.9) | 0.28051 |

| Smoking habit (%) | 161 (46.4) | 13 (48.1) | 0.86061 |

| Hiatal hernia (%) | 136 (39.2) | 17 (63.0) | 0.01551 |

| GMA | |||

| Open type (%) | 177 (51.0) | 12 (44.4) | 0.51111 |

| Erosive esophagitis (%) | |||

| Total | 109 (31.4) | 16 (59.3) | 0.00311 |

| Mild | 97 (28.0) | 15 (55.6) | 0.00261 |

| Severe | 12 (3.5) | 1 (3.7) | > 0.99992 |

Chronic inflammation, such as ulcerative colitis and chronic pancreatitis, is a well known risk factor for cancer formation. As mentioned above, several clinical studies have suggested that the major risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma is Barrett’s epithelium with complicated erosive esophagitis[7-11]. The histological evidence of moderate to severe inflammation, along with the expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-8, and nuclear factor (NF)-κB have been detected in biopsies of Barrett’s epithelium[16,17]. Moreover, the infiltrating inflammatory cells are not the only source of pro-inflammatory cytokines, because Barrett’s epithelial cells themselves have been found to express IL-8, IL-1β, and IL-10[16,18]. NF-κB activation and epithelial cell expression of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and its receptor TNFR1 all have been found to increase as Barrett’s epithelium develops dysplastic changes of progressive severity, which suggests that the inflammatory response might contribute to carcinogenesis[16,19]. Although elevated levels of IL-8 and IL-1β have not been found in dysplastic Barrett’s epithelium, higher expression levels of both cytokines have been detected in esophageal adenocarcinoma[16]. These biohistochemical studies have demonstrated that chronic inflammation caused by gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is an important factor in the etiology of carcinogenesis in Barrett’s epithelium, which suggests an increase in the malignant potential of Barrett’s epithelium, especially when it is accompanied by erosive esophagitis. The identification of a subgroup with a high risk for the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma may be helpful in developing more efficient screening programs for patients with Barrett’s epithelium.

We hypothesized that some macroscopic features of Barrett’s epithelium might be useful for identifying a subgroup with a high risk for the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Therefore, we conducted the present study with the aim of examining the correlation of the shape and length of Barrett’s epithelium with erosive esophagitis.

The present study demonstrated that 43.0% (SSBE, 42.6%; LSBE, 0.5%) of the study population were diagnosed as having Barrett’s epithelium based on the Prague C & M Criteria[12]. These findings were consistent with those from other reports in Japan in which SSBE was frequent, whereas LSBE was rare compared with the United States and Western Europe[20,21]. The frequency of Barrett’s epithelium might be affected by differences in its definition, with particular regard as to whether histological confirmation of specialized intestinal metaplasia is required. In western countries, several physicians think that confirmation of intestinal metaplasia with an esophageal biopsy is needed to identify correctly the pathology as Barrett’s epithelium[22], because it is considered a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma[23]. In this regard, the cases of Barrett’s epithelium in the present study based on the Prague C & M Criteria[12] were diagnosed endoscopically without histological confirmation, and were defined as endoscopic Barrett’s epithelium.

We elucidated a significant correlation between the shape and length of Barrett’s epithelium and prevalence of erosive esophagitis. The prevalence of erosive esophagitis, especially severe esophagitis, was significantly higher in the subjects with F type than L type Barrett’s epithelium (Table 2). F type Barrett’s epithelium might originate as a direct result of columnar replacement of areas damaged by erosive esophagitis. It was possible that F type Barrett’s epithelium had more severe esophagitis because less had been transformed into Barrett’s epithelium, and when the transformation to columnar epithelium had taken place, the previous area with erosive esophagitis would naturally decrease. Yamagishi et al[24] have reported that the localization of Barrett’s epithelium was similar to the localization of mild esophagitis, which was the most prevalent form of erosive esophagitis in Japan, which suggests that tongue-like Barrett’s epithelium arises as a result of erosive esophagitis. The prevalence of erosive esophagitis was significantly higher in subjects with LSBE (Table 3), which was consistent with several studies that have shown that the extent of Barrett’s epithelium is correlated with severe esophageal exposure to acid (an increased percentage of the time during which the esophagus is exposed to a pH below 4)[25-27]. These findings may explain partly why LSBE has a higher risk of the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Harle et al[28] and Ransom et al[29] have suggested a positive relationship between the extension of Barrett’s epithelium and the risk of developing adenocarcinoma in the esophagus. The Rotterdam Esophageal Tumor Study Group has demonstrated that a doubling of the length of Barrett’s epithelium increased the risk of adenocarcinoma by 1.7 times[30].

The present study demonstrated that F type Barrett’s epithelium and LSBE were significantly more strongly associated with erosive esophagitis, as an important factor in the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma, which suggests that patients with Barrett’s epithelium with these macroscopic features are at higher risk for carcinogenesis compared to other types. The development of esophageal adenocarcinoma is usually seen as a sequence - GERD - erosive esophagitis - Barrett’s epithelium - low-grade dysplasia - high-grade dysplasia - esophageal adenocarcinoma. Barrett’s epithelium with these macroscopic features may have a risk of complication of low- or high-grade dysplasia and development of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Our study had several limitations that may need to be considered. First, the data were collected from a review of endoscope images. The shape and length of Barrett’s epithelium evaluated in a retrospective fashion were undoubtedly subject to some uncertainty. To minimize this limitation, we assessed the extent of Barrett’s epithelium based on the Prague C & M Criteria, which consist of two indicators: the C extent and M extent, and defined F type Barrett’s epithelium by the criterion in which the difference between the C extent and M extent should be ≥ 2 cm. Second, the present study might not have had a large enough population to examine in detail the association between the shape and length of Barrett’s epithelium and erosive esophagitis. Third, a disadvantage was the lack of histopathological examination of the samples to confirm the diagnosis, and also the ability to classify further into low- and high-grade dysplasia. Further large population-based cohort studies with histopathological examination of Barrett’s esophagus to classify into low- or high-grade dysplasia are needed to confirm this assumption.

In conclusion, F type Barrett’s epithelium and LSBE were significantly more strongly associated with erosive esophagitis, as an important factor in the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. The identification of a subgroup with these macroscopic features of Barrett’s epithelium may be helpful in developing more efficient screening programs for patients with Barrett’s epithelium. Further prospective large population-based cohort studies are needed to confirm this assumption.

Barrett’s epithelium is recognized as a complication of erosive esophagitis and is the pre-malignant condition for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus.

The authors hypothesized that some macroscopic features of Barrett’s epithelium might be useful for identifying a subgroup with a high risk for the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Recent studies have suggested that the major risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma is the existence of Barrett’s epithelium complicated with erosive esophagitis. The prevalence of erosive esophagitis was significantly higher in subjects with flame-like than with lotus-like Barrett’s epithelium, and in those with a C extent of ≥ 2 cm than < 2 cm.

By understanding the shape of Barrett’s epithelium, this study may represent a future strategy for intervention in the prevention of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

The development of esophageal adenocarcinoma is usually seen as a sequence - gastroesophageal reflux disease - erosive esophagitis - Barrett’s epithelium - low-grade dysplasia - high-grade dysplasia - esophageal adenocarcinoma. Barrett’s epithelium with these macroscopic features may have a risk of complication of low- or high-grade dysplasia and development of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

This is well-written paper on the important subject of trying to identify those subjects with Barrett’s esophagus who might develop esophageal adenocarcinoma. The structure is clear and the presentation is good.

Peer reviewer: Helena Nordenstedt, MD, PhD, Upper Gastrointestinal Research, Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm 17176, Sweden

S- Editor Wang YR L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Mann NS, Tsai MF, Nair PK. Barrett’s esophagus in patients with symptomatic reflux esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:1494-1496. |

| 2. | Winters C Jr, Spurling TJ, Chobanian SJ, Curtis DJ, Esposito RL, Hacker JF 3rd, Johnson DA, Cruess DF, Cotelingam JD, Gurney MS. Barrett’s esophagus. A prevalent, occult complication of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:118-124. |

| 3. | Botterweck AA, Schouten LJ, Volovics A, Dorant E, van Den Brandt PA. Trends in incidence of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and gastric cardia in ten European countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:645-654. |

| 4. | Powell J, McConkey CC, Gillison EW, Spychal RT. Continuing rising trend in oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2002;102:422-427. |

| 5. | Blot WJ, Devesa SS, Fraumeni JF Jr. Continuing climb in rates of esophageal adenocarcinoma: an update. JAMA. 1993;270:1320. |

| 6. | Hongo M, Shoji T. Epidemiology of reflux disease and CLE in East Asia. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38 Suppl 15:25-30. |

| 7. | Lassen A, Hallas J, de Muckadell OB. Esophagitis: incidence and risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma--a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1193-1199. |

| 8. | Lagergren J, Bergström R, Lindgren A, Nyrén O. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:825-831. |

| 9. | Farrow DC, Vaughan TL, Sweeney C, Gammon MD, Chow WH, Risch HA, Stanford JL, Hansten PD, Mayne ST, Schoenberg JB. Gastroesophageal reflux disease, use of H2 receptor antagonists, and risk of esophageal and gastric cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2000;11:231-238. |

| 10. | Wu AH, Tseng CC, Bernstein L. Hiatal hernia, reflux symptoms, body size, and risk of esophageal and gastric adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2003;98:940-948. |

| 11. | Ye W, Chow WH, Lagergren J, Yin L, Nyrén O. Risk of adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and gastric cardia in patients with gastroesophageal reflux diseases and after antireflux surgery. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1286-1293. |

| 12. | Sharma P, Dent J, Armstrong D, Bergman JJ, Gossner L, Hoshihara Y, Jankowski JA, Junghard O, Lundell L, Tytgat GN. The development and validation of an endoscopic grading system for Barrett’s esophagus: the Prague C & M criteria. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1392-1399. |

| 13. | Armstrong D, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Dent J, De Dombal FT, Galmiche JP, Lundell L, Margulies M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ. The endoscopic assessment of esophagitis: a progress report on observer agreement. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:85-92. |

| 14. | Kimura K, Takemoto T. An endoscopic recognition of the atrophic border and its significance in chronic gastritis. Endoscopy. 1969;3:87-97. |

| 15. | Miki K, Ichinose M, Shimizu A, Huang SC, Oka H, Furihata C, Matsushima T, Takahashi K. Serum pepsinogens as a screening test of extensive chronic gastritis. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1987;22:133-141. |

| 16. | O'Riordan JM, Abdel-latif MM, Ravi N, McNamara D, Byrne PJ, McDonald GS, Keeling PW, Kelleher D, Reynolds JV. Proinflammatory cytokine and nuclear factor kappa-B expression along the inflammation-metaplasia-dysplasia-adenocarcinoma sequence in the esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1257-1264. |

| 17. | Fitzgerald RC, Abdalla S, Onwuegbusi BA, Sirieix P, Saeed IT, Burnham WR, Farthing MJ. Inflammatory gradient in Barrett’s oesophagus: implications for disease complications. Gut. 2002;51:316-322. |

| 18. | Fitzgerald RC, Onwuegbusi BA, Bajaj-Elliott M, Saeed IT, Burnham WR, Farthing MJ. Diversity in the oesophageal phenotypic response to gastro-oesophageal reflux: immunological determinants. Gut. 2002;50:451-459. |

| 19. | Tselepis C, Perry I, Dawson C, Hardy R, Darnton SJ, McConkey C, Stuart RC, Wright N, Harrison R, Jankowski JA. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha in Barrett’s oesophagus: a potential novel mechanism of action. Oncogene. 2002;21:6071-6081. |

| 20. | Amano Y, Kushiyama Y, Yuki T, Takahashi Y, Moriyama I, Fukuhara H, Ishimura N, Furuta K, Ishihara S, Adachi K. Prevalence of and risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus with intestinal predominant mucin phenotype. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:873-879. |

| 21. | Akiyama T, Inamori M, Akimoto K, Iida H, Mawatari H, Endo H, Ikeda T, Nozaki Y, Yoneda K, Sakamoto Y. Risk factors for the progression of endoscopic Barrett's epithelium in Japan: a multivariate analysis based on the Prague C & M Criteria. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1702-1707. |

| 22. | Sharma P, Morales TG, Sampliner RE. Short segment Barrett’s esophagus--the need for standardization of the definition and of endoscopic criteria. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1033-1036. |

| 23. | Hamilton SR, Smith RR. The relationship between columnar epithelial dysplasia and invasive adenocarcinoma arising in Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Clin Pathol. 1987;87:301-312. |

| 24. | Yamagishi H, Koike T, Ohara S, Kobayashi S, Ariizumi K, Abe Y, Iijima K, Imatani A, Inomata Y, Kato K. Tongue-like Barrett’s esophagus is associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4196-4203. |

| 25. | Oberg S, DeMeester TR, Peters JH, Hagen JA, Nigro JJ, DeMeester SR, Theisen J, Campos GM, Crookes PF. The extent of Barrett’s esophagus depends on the status of the lower esophageal sphincter and the degree of esophageal acid exposure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117:572-580. |

| 26. | Wakelin DE, Al-Mutawa T, Wendel C, Green C, Garewal HS, Fass R. A predictive model for length of Barrett’s esophagus with hiatal hernia length and duration of esophageal acid exposure. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:350-355. |

| 27. | Avidan B, Sonnenberg A, Schnell TG, Sontag SJ. Hiatal hernia and acid reflux frequency predict presence and length of Barrett’s esophagus. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:256-264. |

| 28. | Harle IA, Finley RJ, Belsheim M, Bondy DC, Booth M, Lloyd D, McDonald JW, Sullivan S, Valberg LS, Watson WC. Management of adenocarcinoma in a columnar-lined esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg. 1985;40:330-336. |

| 29. | Ransom JM, Patel GK, Clift SA, Womble NE, Read RC. Extended and limited types of Barrett’s esophagus in the adult. Ann Thorac Surg. 1982;33:19-27. |