Published online Dec 7, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5685

Revised: October 21, 2009

Accepted: October 28, 2009

Published online: December 7, 2009

AIM: To model clinical and economic benefits of capsule endoscopy (CE) compared to ileo-colonoscopy and small bowel follow-through (SBFT) for evaluation of suspected Crohn’s disease (CD).

METHODS: Using decision analytic modeling, total and yearly costs of diagnostic work-up for suspected CD were calculated, including procedure-related adverse events, hospitalizations, office visits, and medications. The model compared CE to SBFT following ileo-colonoscopy and secondarily compared CE to SBFT for initial evaluation.

RESULTS: Aggregate charges for newly diagnosed, medically managed patients are approximately $8295. Patients requiring aggressive medical management costs are $29 508; requiring hospitalization, $49 074. At sensitivity > 98.7% and specificity of > 86.4%, CE is less costly than SBFT.

CONCLUSION: Costs of CE for diagnostic evaluation of suspected CD is comparable to SBFT and may be used immediately following ileo-colonoscopy.

- Citation: Leighton JA, Gralnek IM, Richner RE, Lacey MJ, Papatheofanis FJ. Capsule endoscopy in suspected small bowel Crohn’s disease: Economic impact of disease diagnosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(45): 5685-5692

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i45/5685.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.5685

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic, transmural inflammatory bowel disease that primarily involves the small bowel. Symptoms of CD are often non-specific and vary among afflicted individuals. Symptoms may include abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding, iron deficiency anemia, weight loss, and fevers[1]. Crohn’s disease can also be associated with extra-intestinal manifestations such as skin rashes, arthritis, and uveitis[2]. While any segment of the gastrointestinal tract can be affected, the small intestine is involved in approximately 70% of patients and up to 30% of patients will have their disease limited solely to the small bowel, particularly the ileum[2].

There is no single test that establishes the diagnosis of CD. Diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical, endoscopic, radiographic, and laboratory findings. The sequence of diagnostic tests attempting to establish the diagnosis of CD is often based upon the patient’s presenting symptoms. For example, when small bowel CD is suspected clinically, ileo-colonoscopy along with small bowel barium radiography [e.g. small bowel follow-through (SBFT)] has traditionally been performed[3]. However, barium radiographic studies are limited by poor sensitivity for detecting early lesions of CD (e.g. aphthous erosions/ulcerations) and ileo-colonoscopy evaluation is confined to only the most distal 5-15 cm of the ileum (terminal ileum). In addition, the non-specific symptoms of CD often lead to delays in obtaining a definitive diagnosis and therefore the institution of appropriate and targeted disease therapy[4-6]. Rath et al[7] found that 38% of CD patients had an interval of more than a year between onset of symptoms and definitive diagnosis.

Because of delays in diagnosing small bowel CD, the costs to payers that are associated with indeterminate tests, repeat endoscopic and radiographic procedures, frequent physician visits, and hospitalizations are likely to be substantial[8,9]. Thus, there is a need for an efficient and effective algorithm of diagnostic tests leading to a definitive diagnosis of CD. Optimizing such a diagnostic pathway should have substantial benefits for both patients and payers.

Until recently, the small bowel has been the most difficult part of the gastrointestinal tract to evaluate endoscopically. Since being introduced in 2001, small bowel capsule endoscopy (CE) has facilitated easy access for direct investigation of the entire small bowel mucosa and as a result has revolutionized the diagnosis and management of small bowel diseases including obscure gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, iron deficiency anemia, CD, polyposis syndromes/tumors, and celiac disease. Because of its ability to examine the entire mucosa of the small intestine, capsule endoscopy has the potential for diagnosing suspected CD patients earlier and as a result, direct costs of care may be reduced.

The aim of this study was to derive and evaluate a decision analytic model to determine the economic benefit of CE compared to ileo-colonoscopy and SBFT for the evaluation of suspected CD of the small bowel.

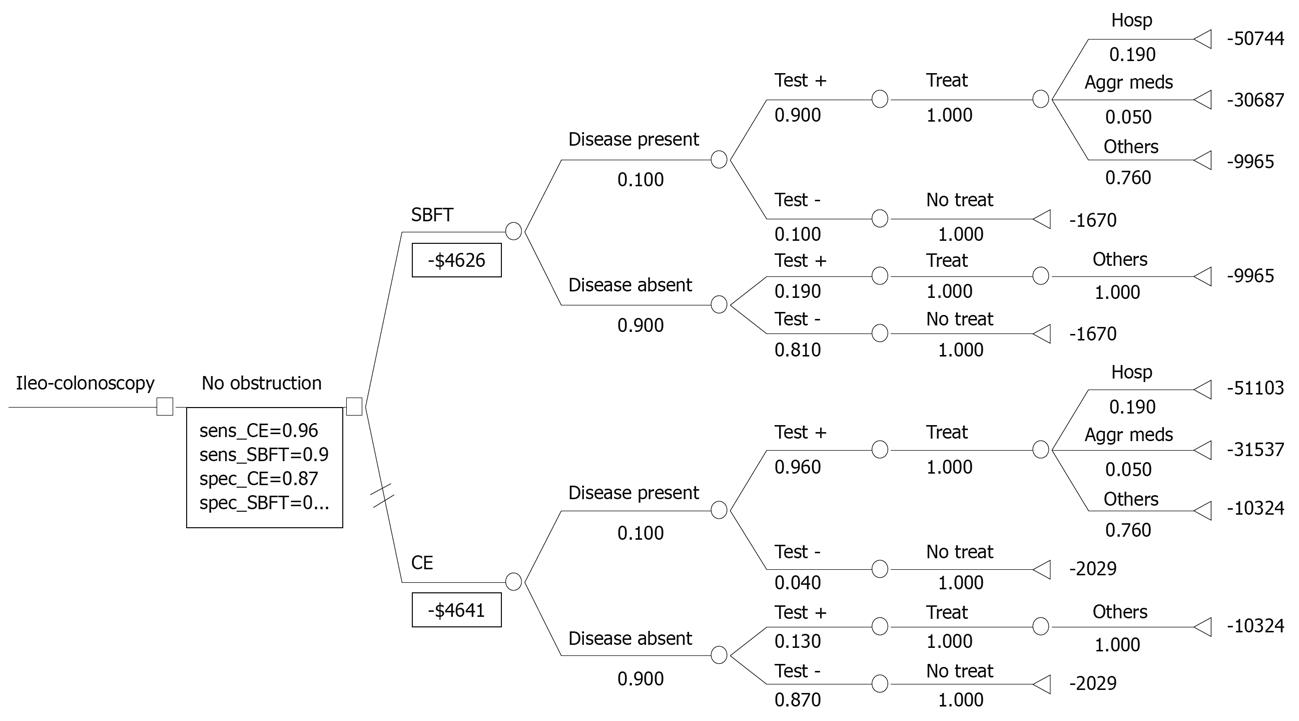

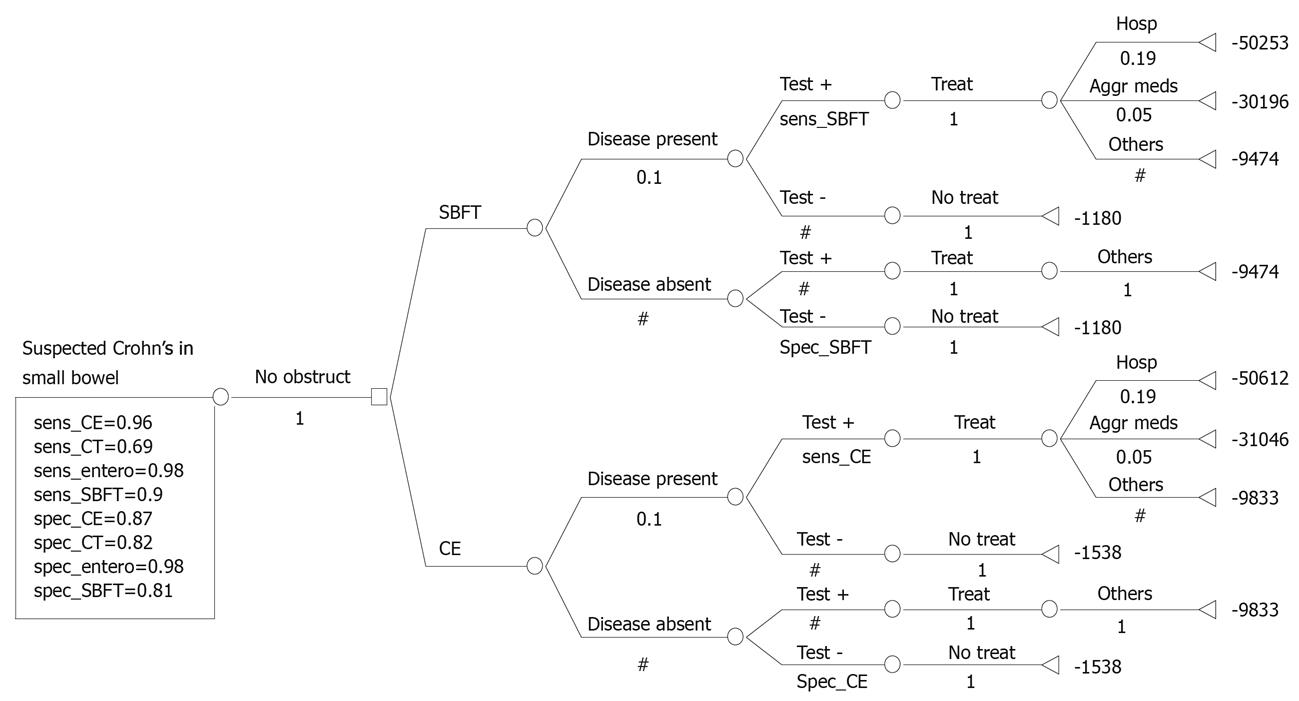

We developed a comprehensive model comparing the direct costs of performing CE for the diagnosis and management of suspected CD in a hypothetical cohort of 10 000 patients. Each arm of the model includes the yield of an initial ileo-colonoscopy immediately followed by SBFT or CE based on current clinical practice and guidelines (Figure 1)[10-16]. If no diagnosis was made after initial ileo-colonoscopy, we assumed that patients would then receive either a SBFT or CE. In a secondary analysis, we eliminated the initial ileo-colonoscopy to determine the relative global costs using SBFT or CE as an initial diagnostic strategy (Figure 2).

In constructing the model to reflect accepted standards of care for suspected CD we used guidance from clinical experts in CD (JAL, IMG) and the 2005 International Conference on Capsule Endoscopy (ICCE) consensus statement[10-17]. For economic comparators, we utilized the economic analysis of Goldfarb et al[18] concerning evaluation of suspected CD using CE and publications identified by a systematic literature review for guidance in building and populating the model.

The Goldfarb economic analysis compared CE to traditional modalities for the diagnosis of suspected small bowel CD[18]. Based on published diagnostic yields of 69.6% for CE vs 53.9% for a combined approach with ileo-colonoscopy and SBFT, their analysis determined CE to be a less costly strategy as long as its diagnostic yield was 64.1% or greater. The authors also reported CE to be less costly as a primary diagnostic tool in this clinical setting[18]. These data are provocative, but CE and ileo-colonoscopy/SBFT as mutually exclusive diagnostic strategies may not translate into every day clinical practice. In addition, the included trials were not subjected to a systematic review analysis to evaluate for study heterogeneity.

Literature review: To estimate key model variables we performed a systematic literature review to investigate the evidence concerning the use of CE for evaluating suspected CD. The MeSH search terms and strategies employed by third party payers were used for identifying relevant publications. Multiple MEDLINE, EMBASE, COCHRANE TRIALS, and BIOSIS searches were completed using MeSH search terms including “capsule endoscopy”, “Pillcam”, “wireless endoscopy”, “wireless capsule endoscopy”, “video endoscopy”, “video capsule endoscopy”, “M2A capsule endoscopy”, “endoscopy”, “ileum endoscopy”, “ileal endoscopy”, “small bowel imaging”, “small intestine imaging”, “Crohn’s disease”, “Crohn’s disease diagnosis”, “Crohn’s disease radiology”, “Crohn’s disease imaging”, “Crohn’s disease costs”, “Crohn’s disease payments”, “Crohn’s disease reimbursement”.

A total of 891 citations were derived from the published literature searches (January 1970 - January 2008). 792 (89%) were published in English and 141 (16%) were review articles; 29 were published in German, 28 in Spanish, 7 each in Japanese and French, and 5 in Italian. In all cases, we reviewed full manuscripts/reports and case reports with sufficient evaluable information but did not include published abstracts. The literature reporting on ultrasound, magnetic resonance (MR), and computed tomography (CT) enterography in CD continues to grow but remains inconsistent in estimates of diagnostic yield and cost; consequently, we chose not to compare these techniques.

Using a decision analysis software (TreeAge Pro Suite 2006 Release 0.3, Williamstown, MA), we evaluated a hypothetical cohort of 10 000 patients who had suspected CD as defined by the 2005 ICCE Consensus conference[17]. Ileo-colonoscopy was negative and was assumed to effectively exclude lesions within the reach of a colonoscope. Therefore, CD lesions modeled were defined to be located proximal to the distal terminal ileum.

This model estimates the total expected global costs to a third party payer of the initial diagnostic work-up as well as expected follow-up costs of managing these patients for one year after diagnosis of CD, including procedure-related adverse events, subsequent hospitalizations, office visits, laboratory tests, and medications. We chose this design because this economic model allows predictive modeling of the annual economic burden for a chronic disease like CD. Payers are concerned about the rate of medical resource utilization of both inpatient and outpatient services and are not generally interested in other burdens to the patient such as sick time off or other opportunity loss. In addition, because of enrollee turnover rates in health plans, payers are most interested in models that study short-term (1-2 years) rather than long-term (> 2 years) economic burdens. Finally, payers are interested in imaging and diagnostic tests that are not additive (i.e. leads to treatment change without requiring further testing).

We developed a cost model based on the annual costs of care for diagnosis and management of a patient with suspected CD[19].

Previously, Feagan et al[19] used medical claims data to identify and stratify patients with CD into three mutually exclusive disease severity groups: Group 1, required an inpatient hospitalization associated with a primary/secondary diagnosis of CD; Group 2, required aggressive pharmacotherapy, defined as chronic glucocorticoid (> 10 mg/d) or immunosuppressive drug (purine antimetabolites/methotrexate) therapy, for > 6 mo and/or anti-TNF monoclonal antibody therapy; or Group 3, all remaining patients (Table 1). As with prior economic evaluations and models reported in the biomedical literature, we used Medicare reimbursement data as surrogates of cost [18,19]. For tests and procedures, the model was populated with national average allowable 2007 Medicare reimbursement data (Table 2).

| HCPCS code | Procedure | Reimbursement | Colonoscopy w/SBFT | Capsule endoscopy |

| 45380 | Colonoscopy, flexible, proximal to splenic flexure; with biopsy, single or multiple | $491.15 | x | x |

| 74249 | Radiological examination, gastrointestinal tract, upper, air contrast, with specific high density barium, effervescent agent, with or without glucagon; with small intestine follow-through | $177.87 | x | |

| 88305 | Level IV-surgical pathology, gross and microscopic examination | $115.38 | x | |

| 88323 | Consultation and report on referred material requiring preparation of slides | $150.09 | x | |

| 91110 | Gastrointestinal tract imaging, intraluminal (e.g. capsule endoscopy), esophagus through ileum, with physician interpretation and report | $950.00 | x | |

| 99242 | Office (gastroenterologist) consultation (Level 2) | $97.37 | x | x |

| Additional Medications1 | $50 | |||

| Total | $1179.00 | $1538.00 |

We were interested in determining total payer costs associated with the diagnostic evaluation and management of suspected CD. Therefore we evaluated typical hospitalization, outpatient, and medication costs associated with the care of a patient being evaluated for suspected CD of the small bowel. To estimate the added cost of anti-TNF monoclonal antibody therapy (e.g. Remicade®), we identified cost-effectiveness analyses on the use of these agents for treatment of aggressive CD. Recent literature has estimated that 25% of patients in this group would receive anti-TNF monoclonal antibody therapy[20,21]. Based on the reported shifts in utilization, we estimated an annual cost of $65 000 for this class of drugs and calculated a weighted average cost of $16 250 per patient to simulate the expected cost of these agents in the aggressive medical management group (Feagan et al[19] Group 2).

Annual costs were then estimated as a weighted average based on the likelihood of the correct diagnosis multiplied by the expected costs of follow-up care by each patient type. We estimated in-patient hospital costs by examining charge data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) which is one in a family of databases and software tools developed as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), a Federal-State-Industry partnership sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Rockville, MD). This database permits searches of in-patient costs according to ICD-9 disease classifications. The database includes historical information and permits comparisons to inflation-adjusted calculations.

The systematic literature review described above was used to identify mean sensitivity and specificity estimates for the comparator diagnostic techniques (Table 3). These values were used to populate the model as were the inflation-adjusted charges described in the manuscript by Feagan et al[19]. In addition, a series of sensitivity analyses, including a Monte Carlo analysis, were performed to determine the relative strengths and weaknesses of utilizing CE relative to other diagnostic testing options in patients with suspected CD. Monte Carlo simulation creates a multi-way sensitivity analysis. The base-case decision tree was repeatedly analyzed using inputs with appropriate distributions to determine the proportion of runs each strategy was identified as the least costly initial strategy. The following variables were used in the simulation: costs and sensitivity of tests and rates of procedural complications. Each simulation performed included 10 000 trials. Adding the potential cost of complication(s) following possible capsule retention did not change the economic results (data not shown).

| Input | Mean (range) | Ref. |

| CE sensitivity (sens_CE) | 0.96 (0.80-0.99) | [3,14-17,26,27] |

| CE specificity (spec_CE) | 0.87 (0.80-0.99) | [3,14-17,26,27] |

| SBFT sensitivity (sens_SBFT) | 0.96 (0.80-0.99) | [3,14-17,26,27] |

| SBFT specificity (spec_SBFT) | 0.81(0.80-0.99) | [3,14-17,26,27] |

| Disease present/absent | 0.10/0.90 | [1,2,4] |

| Hospitalization frequency (Group 1) | 0.19 | [18] |

| Aggressive medical management frequency (Group 2) | 0.05 | [18] |

| Other management frequency (Group 3) | 0.76 | [18] |

Figure 2 depicts the derived cost model. All patients with suspected CD are initially examined with ileo-colonoscopy followed by SBFT or CE. Overall, patients evaluated and treated by the CE pathway cost $4641 whereas those evaluated by SBFT cost $4626, a difference of $15 per patient slightly in favor of SBFT. Patients with positive small bowel findings on CE who required hospitalization cost $51 103 and those requiring aggressive medical management cost $31 537. These values were comparable to the SBFT pathway. In the secondary analysis, patients managed by CE as the initial diagnostic test cost $4150 or $15 per patient more than those initially evaluated with SBFT. These results were comparable to the prior results because of the lower cost of omitting an initial ileo-colonoscopy at an estimated cost of $491.

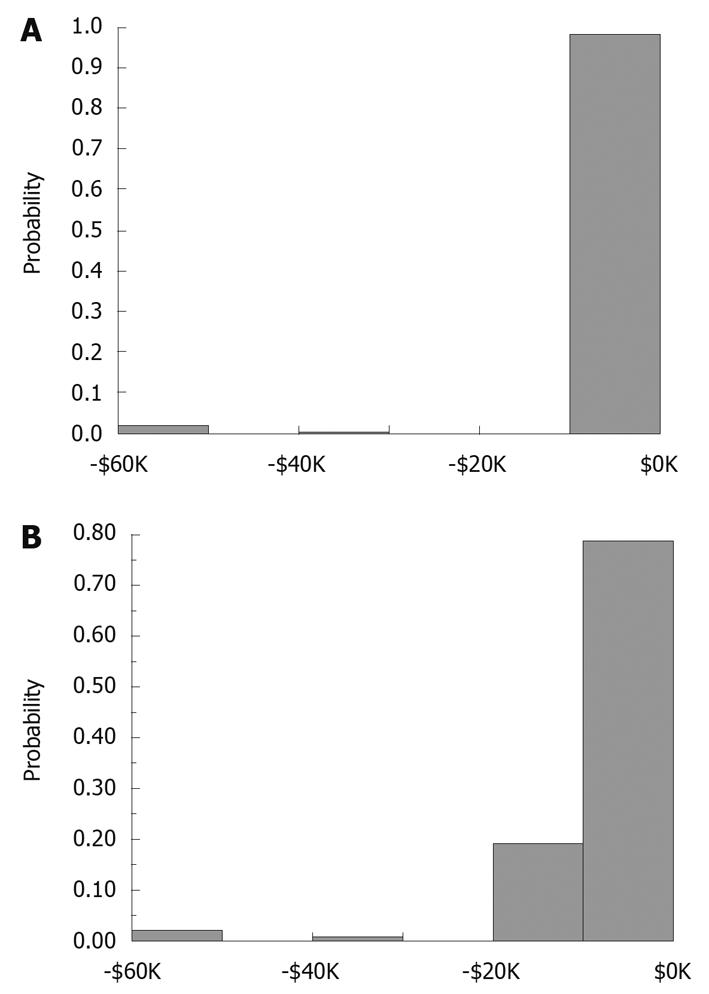

We conducted a Monte Carlo simulation involving 10 000 patients undergoing evaluation for suspected CD. In evaluating the results shown in Figure 3, there is evidence that the probability of incurring a charge of at least $1670 is > 97.5%; there is less than a 2.5% probability of incurring a charge of more than $9965. The mean cost for evaluation of the patient with suspected small bowel CD is $4601 ± 7467 (SD) for this 10 000 patient model cohort examined by ileo-colonoscopy first, immediately followed by SBFT. Likewise, there is evidence that the probability of incurring a charge of at least $2029 is > 97.5%; there is less than a 2.5% probability of incurring a charge of more than $10 324 in those evaluated by ileo-colonoscopy first, immediately followed by CE. The mean cost for evaluating a patient with suspected CD in that group is $4604 ± 7563 (SD) for the 10 000 patient simulation. The results of the Monte Carlo simulation are essentially identical ($4604 for SBFT vs $4601 for CE) for each technique and represent a real-world scenario of relevant costs.

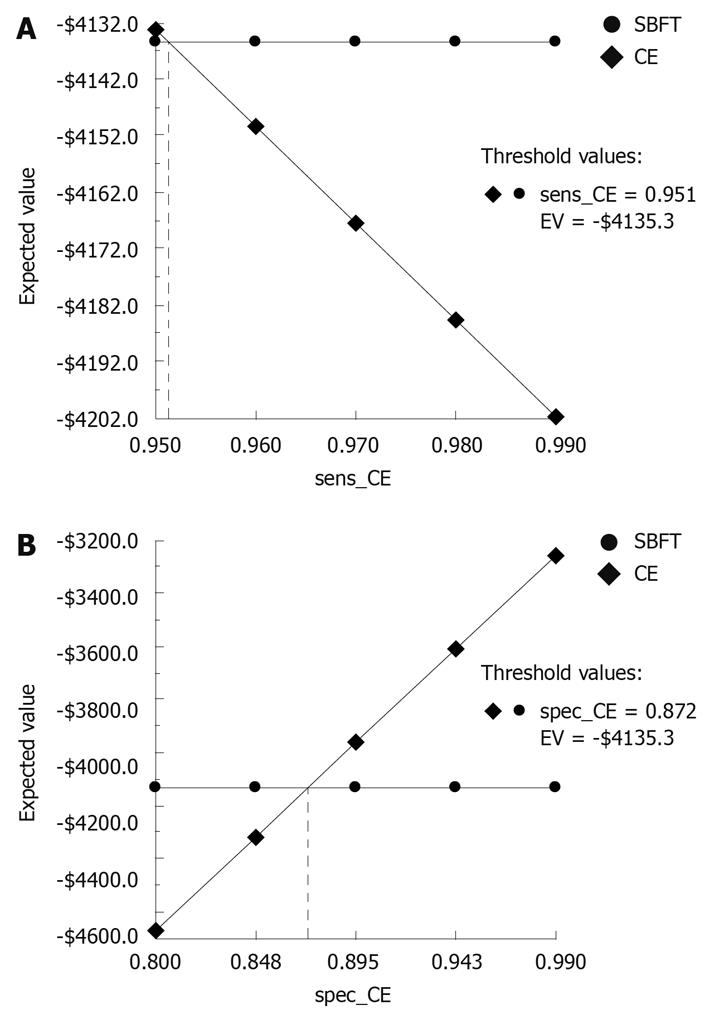

The results of one-way sensitivity analyses on the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of SBFT and CE are shown in Figure 4 for patients who receive an initial ileo-colonoscopy. The graphs depict how sensitivity (x-axis) and cost (y-axis) (i.e. expected value) interplay. As expected, the cost of performing either test decreases with increasing sensitivity or specificity. The cost of performing SBFT vs CE is essentially equivalent over a wide range of sensitivity values, particularly in the highest ranges of sensitivity and specificity, which might be achieved by an experienced clinician. At a sensitivity > 95.1%, CE becomes less costly than SBFT; at a specificity of > 87.2%, CE is less costly than SBFT. As expected, the results are identical in the secondary analysis (data not shown).

Capsule endoscopy is a valuable tool for the study of patients in whom a clinical suspicion of small bowel CD is raised. We found in this present study, applying a conservative costing methodology, incorporating ileo-colonoscopy with SBFT, and CE, demonstrates that CE is marginally less costly overall than use of SBFT despite CE being a slightly more costly test. Secondary analysis demonstrates the cost advantage of CE is robust over a wide range of diagnostic sensitivity and specificity values. Thus, following ileo-colonoscopy, there appears to be evidence and a cost basis to encourage the use of CE initially (e.g. in place of SBFT) in diagnostic algorithms for suspected small bowel CD.

Suspected CD patients often go months and sometimes years without a definitive diagnosis, especially those with more mild or moderate symptoms and with disease that is isolated to the small bowel. For example, ileo-colonoscopy may be normal in such individuals and a functional bowel disorder may be suspected. Symptoms of CD, especially in the early stages, may mimic functional bowel disease, such as irritable bowel syndrome, confounding the differential diagnosis[19]. Radiographic diagnostic tests such as SBFT may not be sensitive enough to detect early small bowel mucosal changes (aphthae) and enteroclysis, although a more sensitive test than SBFT is no longer routinely used due to the difficulty of performing the exam, its limited availability, and patient discomfort associated with the procedure. Moreover, exposure to radiation with these tests is a genuine concern among patients and physicians. As a result, these standard radiographic diagnostic testing approaches (SBFT and enteroclysis) can contribute to a delay in diagnosis and hence costs to the payer. While CT enterography may be a superior imaging modality to SBFT and enteroclysis for suspected CD, at present the test has limited clinical availability and as such, SBFT remains the initial study following ileo-colonoscopy in most clinical practices. For those patients with a negative ileo-colonoscopy and negative SBFT in whom obstructive symptoms raise concern for possible capsule retention, CT enterography or the Agile Patency Capsule performed prior to standard small bowel capsule endoscopy may be the next best option to evaluate these patients.

There are a number of limitations to this present study. The model inputs for the test characteristics for diagnostic tests were extracted from the literature based on clinical studies that included selected patients. These patient populations may not reflect the spectrum of patients seen in usual clinical practice. We have attempted however, to temper this limitation by performing sensitivity analyses over a wide range of model estimates, including a Monte Carlo simulation[22]. Another limitation of this study is that there are only a limited number of publications that report findings on the use of CE for CD. Moreover, sample sizes in these trials have invariably been small. However, a meta-analysis of available prospective trials comparing CE with one or more alternate diagnostic modalities for the diagnosis of suspected or established CD, found an incremental yield of 43% (95% CI = 29% to 56%) for CE over SBFT for the diagnosis of small bowel CD, with a number needed to test of only 2 patients for an additional positive finding with CE[23]. An updated meta-analysis showed that the yield favors CE compared to SBFT for suspected CD[24-26]. Analysis of CE vs colonoscopy with ileoscopy (incremental yield with CE = 16%, 95% CI = 3% to 30%) and CT enterography/enteroclysis (incremental yield with CE = 32%, 95% CI = 3% to 61%) also found a significantly improved yield with CE. We utilized data from these meta-analyses to better populate our model estimates.

Our cost-analysis was limited to a third-party payer perspective, although there are additional relevant perspectives. For example, indirect costs to the patient and the cost to the gastroenterologist and their capacity to deliver care (provide CE examination) was not evaluated. In the case of the ability of gastroenterologists to provide care, CE is now a widely accepted diagnostic test that most gastroenterology practices have available and utilize. Moreover, the time horizon for this analysis was limited to one year. However, payers are most interested in models that study short-term (1-2 years) rather than long-term (> 2 years) economic burdens due in part to attrition of members in health plans.

Though CE is a promising technology for the evaluation of patients with CD, there are a number of concerns with its use in this population. The possibility of capsule retention due to known or suspected strictures is a concern in this patient group. The rate of capsule retention in the largest published series of CE for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding was 0.75% (7/934 patients) despite a negative SBFT in 6/7 patients[27]. All patients underwent surgical resection, and pathology explaining the reason for each patient’s symptoms was found at the site of capsule impaction (a so-called therapeutic complication). Due to the stenosing nature of CD, however, a higher rate of capsule retention may be expected if CE is performed in these patients. Rates of capsule retention in patients with CD range from 0% to 13% despite small bowel imaging performed prior to CE in nearly all patients[28,29]. However, the rate of capsule retention is significantly higher in patients with known CD compared to those with suspected CD.

Perhaps the most significant issue facing CE in the evaluation of CD is the lack of specificity and its inability to provide pathologic confirmation of observed findings. In clinical studies, a variety of findings encompassing a broad range of severity have been described as potentially consistent with the diagnosis of CD, and thereby a positive result with CE. As a diagnosis of CD has far-reaching effects on the psychological and financial health of patients as well as their physical health, caution in making this diagnosis based on subtle CE findings is appropriate. The long-term clinical significance of finding occasional mucosal breaks in the small bowel on CE is presently unclear, and will require prospective studies to clarify the issue.

In summary, this economic model, along with several clinical trials suggest that CE is a valuable tool in the diagnosis and subsequent management of patients with suspected CD. Data from the studies reviewed in this article suggest improved outcomes after CE due to targeted medical therapy for those patients found to have lesions consistent with CD, as well as a change in therapeutic strategy in those patients with normal capsule examinations[25,30]. The burden of delay in definitive diagnosis of a debilitating chronic disease is never more apparent than in CD where earlier intervention and treatment makes a significant clinical impact. New technologies and diagnostics, such as CE, require evidence from clinical and payer decision makers who demand rigorous proof of clinical and economic utility. This model provides economic evidence in favor of CE for use immediately following ileo-colonoscopy in the diagnostic pathway for suspected CD.

Using capsule endoscopy (CE) earlier in diagnosis of suspected Crohn’s Disease (CD) may reduce direct costs of care due to ability to examine the entire mucosa of the small intestine; currently, no single test establishes this diagnosis.

Accurate, early diagnosis of CD is important to patient management decisions. Current therapies may be expensive and their potential inappropriate clinical use due to incorrect diagnosis is troublesome. CE represents a diagnostic technology that may improve overall diagnostic yield therein obviating potentially substantial clinical and economic loss.

CE is an important breakthrough diagnostic technology that is used in a wide number of clinical settings. The present analysis considers its use in suspected small bowel CD. The findings here extend previous cost analyses. The economic model presented here is the first to combine diagnostic and therapeutic costs associated with this condition.

The results of this study may assist in developing cost-effective diagnostic guidelines for evaluation of suspected CD.

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic, transmural inflammatory bowel disease that primarily involves the small bowel. Capsule endoscopy (CE) is a technique that directly visualizes the surface of the small bowel where abnormalities due to CD may be identified.

This study presents a valuable economic model that combines the cost-effectiveness of diagnosis and treatment of patients with suspected CD. The results demonstrate the value of capsule endoscopy in the overall management of patients with this condition. These results may be useful in future studies of cost-effective approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of CD as well as to considerations of diagnostic selection in clinical guidelines and practice.

Peer reviewer: Kevin Cheng-Wen Hsiao, MD, Assistant Professor, Colon and Rectal Surgery, Tri-Service General Hospital, No. 325, Sec. 2, Cheng-Kung Rd, Nei-Hu district, 114 Taipei, Taiwan, China

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor O'Neill M E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Mekhjian HS, Switz DM, Melnyk CS, Rankin GB, Brooks RK. Clinical features and natural history of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:898-906. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Lashner B. Bowel disease. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders 2000; 305-314. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Delvaux M, Fassler I, Gay G. Clinical usefulness of the endoscopic video capsule as the initial intestinal investigation in patients with obscure digestive bleeding: validation of a diagnostic strategy based on the patient outcome after 12 months. Endoscopy. 2004;36:1067-1073. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Farmer RG, Hawk WA, Turnbull RB Jr. Clinical patterns in Crohn’s disease: a statistical study of 615 cases. Gastroenterology. 1975;68:627-635. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Pimentel M, Chang M, Chow EJ, Tabibzadeh S, Kirit-Kiriak V, Targan SR, Lin HC. Identification of a prodromal period in Crohn’s disease but not ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3458-3462. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Burgmann T, Clara I, Graff L, Walker J, Lix L, Rawsthorne P, McPhail C, Rogala L, Miller N, Bernstein CN. The Manitoba Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort Study: prolonged symptoms before diagnosis--how much is irritable bowel syndrome? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:614-620. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Rath HC, Andus T, Caesar I, Scholmerich J. [Initial symptoms, extra-intestinal manifestations and course of pregnancy in chronic inflammatory bowel diseases]. Med Klin (Munich). 1998;93:395-400. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Bernstein CN, Kraut A, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, Yu N, Walld R. The relationship between inflammatory bowel disease and socioeconomic variables. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2117-2125. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | The economic costs of Crohn’s Disease and ulcerative colitis. Australian Crohn’s and Colitis Association, 2007. Accessed November 13, 2008. Available from: http://www.accesseconomics.com.au/publicationsreports/showreport.php?id=130&searchfor=2007&searchby=year. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Lichtenstein GR, Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ. Management of Crohn’s disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:465-483; quiz 464, 484. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Sidhu R, Sanders DS, Morris AJ, McAlindon ME. Guidelines on small bowel enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy in adults. Gut. 2008;57:125-136. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Raju GS, Gerson L, Das A, Lewis B. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute medical position statement on obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1694-1696. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Hirano I, Richter JE. ACG practice guidelines: esophageal reflux testing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:668-685. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Rey JF, Ladas S, Alhassani A, Kuznetsov K. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE). Video capsule endoscopy: update to guidelines (May 2006). Endoscopy. 2006;38:1047-1053. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Mishkin DS, Chuttani R, Croffie J, Disario J, Liu J, Shah R, Somogyi L, Tierney W, Song LM, Petersen BT. ASGE Technology Status Evaluation Report: wireless capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:539-545. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Rey JF, Spencer KB, Jurkowski P, Albrecht HW. ESGE guidelines for quality control in servicing and repairing endoscopes. Endoscopy. 2004;36:921-923. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Kornbluth A, Colombel JF, Leighton JA, Loftus E. ICCE consensus for inflammatory bowel disease. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1051-1054. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Goldfarb NI, Pizzi LT, Fuhr JP Jr, Salvador C, Sikirica V, Kornbluth A, Lewis B. Diagnosing Crohn’s disease: an economic analysis comparing wireless capsule endoscopy with traditional diagnostic procedures. Dis Manag. 2004;7:292-304. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Feagan BG, Vreeland MG, Larson LR, Bala MV. Annual cost of care for Crohn’s disease: a payor perspective. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1955-1960. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Bodger K. Economic implications of biological therapies for Crohn’s disease: review of infliximab. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23:875-888. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Kaplan GG, Hur C, Korzenik J, Sands BE. Infliximab dose escalation vs. initiation of adalimumab for loss of response in Crohn’s disease: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1509-1520. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Cook J, Drummond M, Heyse JF. Economic endpoints in clinical trials. Stat Methods Med Res. 2004;13:157-176. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Triester SL, Leighton JA, Leontiadis GI, Fleischer DE, Hara AK, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to other diagnostic modalities in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2407-2418. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Fidder HH, Nadler M, Lahat A, Lahav M, Bardan E, Avidan B, Bar-Meir S. The utility of capsule endoscopy in the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease based on patient’s symptoms. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:384-387. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Cohen SA, Gralnek IM, Ephrath H, Saripkin L, Meyers W, Sherrod O, Napier A, Gobin T. Capsule endoscopy may reclassify pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a historical analysis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:31-36. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Triester SL, Leighton JA, Leontiadis GI, Gurudu SR, Fleischer DE, Hara AK, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to other diagnostic modalities in patients with non-stricturing small bowel Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:954-964. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Barkin JS, O’Loughlin C. Capsule endoscopy contraindications: complications and how to avoid their occurrence. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2004;14:61-65. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Buchman AL, Miller FH, Wallin A, Chowdhry AA, Ahn C. Videocapsule endoscopy versus barium contrast studies for the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease recurrence involving the small intestine. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2171-2177. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Cheifetz AS, Kornbluth AA, Legnani P, Schmelkin I, Brown A, Lichtiger S, Lewis BS. Incidence and outcome of the retained video capsule endoscope (CE) in Crohn’s disease (CD): is it a “therapeutic complication”? (Abstract 807). Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:S262. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Solem CA, Loftus EV Jr, Fletcher JG, Baron TH, Gostout CJ, Petersen BT, Tremaine WJ, Egan LJ, Faubion WA, Schroeder KW. Small-bowel imaging in Crohn’s disease: a prospective, blinded, 4-way comparison trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:255-266. [Cited in This Article: ] |