CASE REPORT

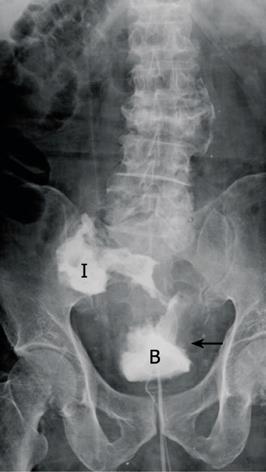

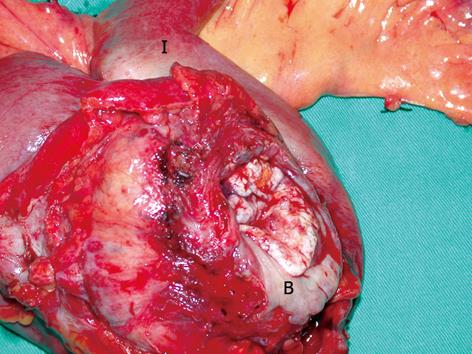

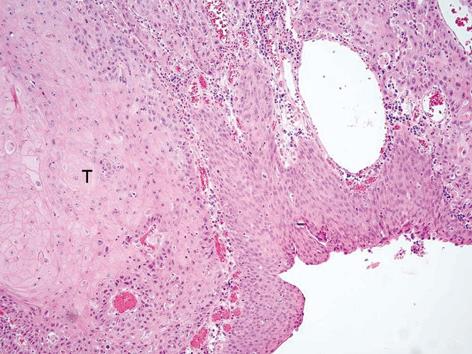

An 83 year-old male presented with a 4-mo history of recurrent urinary tract infection. He had a history of benign prostate hyperplasia (American Urology Association score 24) that was under medical treatment. In order to correct urine retention and prevent urinary tract infection, photosensitive vaporization of the prostate had been performed. One month after the operation, the patient suffered from urinary tract infection again. The urine culture contained multiple flora of the gastro-intestinal tract including: Escherichia coli, Viridans streptococcus, Klebsiella, Pneumoniae and Enterococcus faecium. Retrograde urethrography showed leakage of the contrast and cystoscopy disclosed a fistula in the right posterior wall of the bladder with edematous tissue surrounding the fistula (Figure 1). Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography showed a very large neoplasm in the pelvic cavity with suspicion of vesicoileal fistula formation. Under the impression of malignant enterovesical fistula, the patient underwent surgical intervention. At laparotomy, a 10 cm-diameter whitish stony hard tumor was located in the pelvis, involving the distal ileum and urinary bladder, with a frank fistula formation. Resection of the urinary bladder dome and the involved ileum was performed in en bloc fashion (Figure 2). The pathology report yielded a moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder with direct invasion of the terminal ileum (Figure 3). This patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged without urinary tract infection on post-operative day 7.

DISCUSSION

Enterovesical fistula is a rare disease, with an estimated two to three patients per 10 000 hospital admissions, with annular incidence of 0.5 per 100 000[1]. In a literature review, 20% of vesicoenteral fistulas were rectovesical fistulas and 4%-5% were appendicovesical fistulas. Carson et al[2] reported 100 cases of enterovesical fistulas with 51% colonic diverticulitis, 16% colorectal cancer, 5% urinary bladder carcinoma and 16% due to other causes, including secondary to radiation necrosis, cervical cancer, tuberculoma and iatrogenic perforation.

The most common histologic type of bladder cancer leading to enterovesical fistula is transitional cell carcinoma. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder is a relatively rare tumor. The prevalence of squamous cell carcinoma varies depending on geographic location. It accounts for only 3%-7% of bladder cancers in the United States and 1% in England, but up to 75% in Egypt, where schistosomiasis is endemic[4]. Squamous cell carcinoma are usually related to chronic infection, bladder stones, chronic indwelling catheters or bladder diverticula. To our knowledge, this is the first report of vesicoenteral fistula as a result of bladder squamous cell carcinoma. Only one case of vesicorectal fistula from invasive rectal squamous cell carcinoma cancer had been reported[5]. Almost all squamous cell carcinomas are already advanced and muscle-infiltrative at the time of diagnosis[6]. Squamous cell carcinomas of the bladder have an unfavorable prognosis due to a local advanced stage at the time of presentation.

The most common clinical presentations of enterovesical fistulas are urinary tract infection (100%), pneumaturia (66%), fecaluria (50%), and hematuria (22.6%)[3].

Diagnostic tests include cystoscopy examination, retrograde cystography, and computed tomography. The diagnostic rate using cystoscopy examination is 77%-79%[2,7], while retrograde cystogram and computed tomography showed the fistulous tract in 66.6% and 83.3%, respectively[8,9]. Barium enema or small bowel series have a 20%-35% diagnostic rate to indicate the fistula[4]. Under cystoscopy examination, the fistula may be seen within a hypereremic area at an early stage of the disease, and with cystic mucosal hyperplasia or localized granulation tissue at the late stage[10,11]. Computed tomography has the advantage of showing the fistula tract or gas distinctly in the bladder. In addition, it is useful in delineating the extent of disease involvement, visualizing the anatomic relationship of the adjacent organs and detecting distant metastasis for malignant diseases, which accordingly allows tailoring of the management strategy[7,12,13].

Optimal work-up of a malignant of enterovesical fistula includes detection of the fistula and anatomic extension using the aforementioned diagnostic tests and definitive pathological confirmation, if possible. Except for elderly people in generally poor condition, diverting enterostomy and indwelling urethral catheters are not recommended as permanent treatments for enterovesical fistulae[3].

Whitely and Grabtald proposed that a one-stage en bloc resection of the colonic malignancy and involved bladder portion is a reasonable and safe procedure[7,11], avoiding a total cystectomy. Patients must be well-prepared, non-obstructive and without systemic infection before the surgery[1,11,12,14,15]. However, if resection of the bladder is too wide, resulting in a total cystectomy, reconstruction to restore intestinal continuity and provide adequate bladder capacity and continence is pertinent. On the other hand, if the tumor is deemed unresectable and there is a short life expectancy, a palliative surgical procedure with enterostomy, with or without urinary diversion, is suggested[12,16].

The 5-year survival rate for colon cancer with enterovesical fistula is 81% in nodal negative patients (T4N0), compared with 27% in nodal positive patients (T4N1)[17]. Looser et al[16] also suggested that colonic cancer with a perforation into the bladder could be treated by resection for a curative purpose, obtaining long-term survival in 50% of the patients[7,16]. Nevertheless, Vidal Sans et al[3] reported that surgical morbidity and mortality is relatively high, especially in fistula resulting from malignancy. Despite various methods of treatment for enterovesical fistula, the prognosis for patients with an advanced stage of malignant fistulae is dismal.