Published online Aug 7, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4709

Revised: June 10, 2008

Accepted: June 17, 2008

Published online: August 7, 2008

Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater is extremely rare and different from the common ampullary adenocarcinoma. The ampullary adenoma is also a rare neoplasm and has the potential to develop an adenocarcinoma. Their coexistence has been rarely reported in the literature. We herein describe an unusual case of a small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma associated with a villous adenoma in the ampulla of Vater with emphasis on computed tomography (CT) and histopathological findings. We also discuss their clinical, histopathological and radiological features as well as possible histogenesis.

- Citation: Sun JH, Chao M, Zhang SZ, Zhang GQ, Li B, Wu JJ. Coexistence of small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and villous adenoma in the ampulla of Vater. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(29): 4709-4712

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i29/4709.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.4709

Primary extrapulmonary small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma is rare, occurring in only 4% of all patients with small cell carcinomas[1]. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma presents 0.1%-1% of all gastrointestinal malignant tumors with varying incidence in different organs[2]. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater is extremely rare and different from the common ampullary adenocarcinoma[3]. The ampullary adenoma is also a rare neoplasm and has the potential to develop an adenocarcinoma[4]. Only two cases of a small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma associated with an adenoma have been described by Nassar et al[5]. To our knowledge, there has been no report describing the imaging features of these coexisting tumors of the ampullary region. Here we report the computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) findings of an unusual case of a small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma associated with a villous adenoma in the ampulla of Vater, and review their clinical and histopathologic features.

A 74-year-old man presented with a 3-wk history of abdominal discomfort and jaundice. Physical examination showed icterus and a palpable gall bladder. Laboratory findings were: total bilirubin, 11.19 mg/dL (normal 0.3-1.5); direct bilirubin, 6.91 mg/dL (normal 0.01-0.35); serum albumin, 3.14 g/dL (normal 3.5-5.0); alanine aminotransferase, 209 U/L (normal 0-50); aspartate aminotransferase, 197 U/L (normal 0-40); γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, 1610 U/L (normal 0-40); alkaline phosphatase, 1419 IU/L (normal 30-140); and carbohydrate antigen 19-9, 657.4 U/mL (normal < 37).

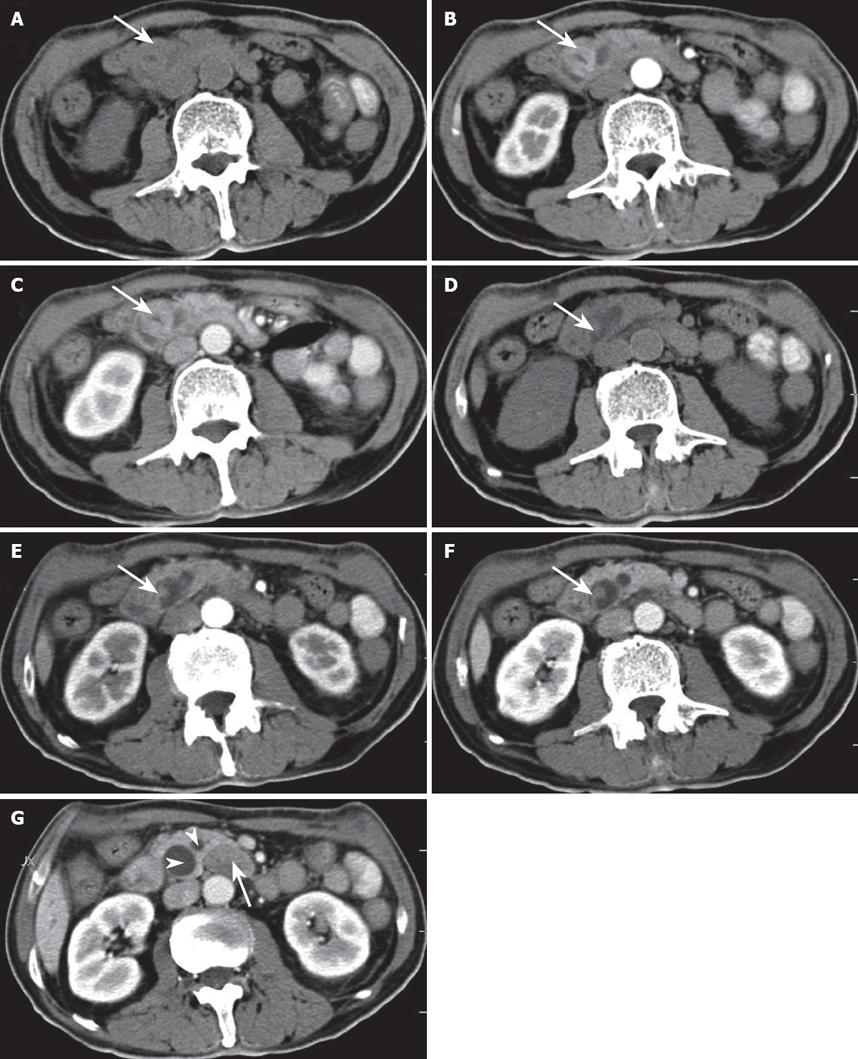

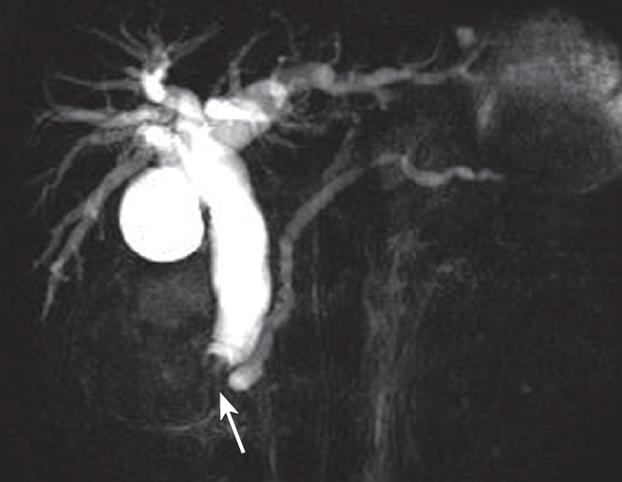

Gastroduodenal endoscopy showed a swollen duodenal papilla with the intact mucosal surface. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a heterogeneous hypoechoic mass in the ampulla of Vater and markedly dilated bile ducts over the neoplasm. Abdominal CT showed two well-defined masses, dilated bile ducts and peripancreatic lymphadenopathy (Figure 1). On precontrast CT scanning, the two masses were isoattenuated to the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma (Figure 1A and D). On arterial and portal phase images after contrast enhancement, the larger oval mass was slightly hyperattenuated to the surrounding pancreas and showed the stenosis of the ampulla of Vater in its central portion (Figure 1B and C). The smaller polypous mass with a pedicle was slightly hypoattenuated to the surrounding pancreas (Figure 1E and F). MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) showed the dilated biliary tree up to the level of the ampulla, where the common bile duct ended abruptly (Figure 2). The low- signal intensity mass was demonstrated immediately inferiorly to the level of the obstruction. The pancreatic duct was moderately dilated.

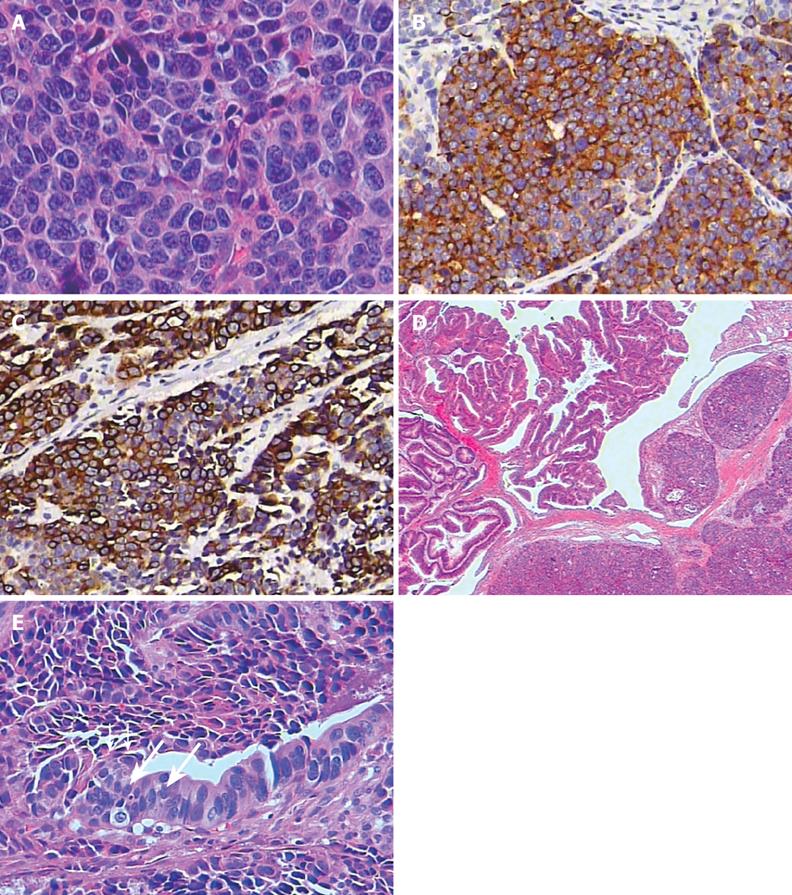

The patient underwent Whipple’s operation with local lymph node dissection. At operation there was a 1.5 cm × 2 cm yellowish gray tumor located mainly in the submucous layer of the ampulla. A polyp with a 6 mm × 6 mm spherical head and a relatively long pedicle and stalk was found in the vicinity of the tumor and extended to the distal common bile duct. Histologically, the tumor proliferated in a nesting pattern. Patchy necrosis was present. The tumor was composed predominantly of small to medium-sized, round or oval cells with a high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, finely dispersed chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and high mitotic activity (more than 10 per 10 high power microscopic fields) (Figure 3A). Lymphatic permeation was seen, but no obvious venous involvement was identified. Immunohistochemically, neoplastic cells were positive for synaptophysin and low-molecular-weight cytokeratin (Figure 3B and C). Ki-67 immunostaining revealed a proliferation index of more than 80%. The associated adenomatous polyp with villous structures as well as foci of areas of moderate and severe dysplasia was seen in the ampullary mucosa (Figure 3D). The dysplastic epithelium of the adenoma was in continuity with the invasive tumor (Figure 3E). Unfortunately, the patient died of pneumonia 3 mo after the operation.

Ampullary small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma is extremely rare and has only been documented in few case reports and retrospective studies[25]. The patients with ampullary small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma usually presented after the age of 60 years (mean age, 63.5 years), and a male predilection was observed[6]. The tumor is a poorly differentiated, high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma and resembles its counterpart originating from the tracheobronchial tree in its aggressive behavior and high propensity for early lymph node metastases and distant metastases[235].

Pancreatoduodenectomy with local lymph node dissection is currently the standard surgical treatment for the ampullary cancer[7]. No effective postoperative chemotherapies for ampullary small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma have been established. Chemotherapy or radiation has been reported to be effective for some cases of the tumor of the gastrointestinal tract and the biliary system[28]. The prognosis of these patients with small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma was poor, the survival period even after operation usually being less than a year[269].

Ampullary adenoma and adenocarcinoma are tumors that originate in the glandular epithelium of the ampulla of Vater. The progression from adenoma to carcinoma in the ampulla of Vater is similar to that in colon[10]. Some cases of ampullary small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma associated with or mixed with adenoma, adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma have been reported[511]. These associations suggest a common origin of small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and adenoma at this site. It is likely that the two neoplasms originate from non-neoplastic multipotent stem cells that terminally differentiate into all kinds of epithelial cells including ciliated cells, mucous cells and endocrine cells. However, the molecular data suggest that there are significant differences in the pathogenesis of the various types of tumors of the ampulla.

Ampullary small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas have histologic appearance similar to their pulmonary counterparts[6]. They are usually comprised of solid sheets of pleomorphic cells with small round-to-oval hyperchromatic nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio. On immunohistochemical examination, the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors must be confirmed by positive immunohistochemical staining for at least 1 neuroendocrine marker, such as chromogranin or synaptophysin[12]. In our case, the diagnosis of small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma was based on typical morphological and immunohistochemical findings. In addition, neoplastic cells exhibited cytoplasmic immunostaining for cytokeratin and nuclear Ki-67 positivity (a proliferation index of more than 80%). We postulate that this neoplastic histogenesis was from epithelial stem cells with both epithelial and neuroendocrine characteristics.

The preoperative diagnosis of these rare tumors in the ampulla is potentially problematic. In most cases with ampullary tumors, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with biopsy is valuable for making a definitive preoperative diagnosis in patients with ampullary tumors. However, it is very difficult to diagnose intramural ampullary neoplasm at endoscopy because the papilla is covered with normal duodenal mucosa. Although MRCP and CT can show obstruction of the ampulla of Vater, CT is known to be more accurate for demonstrating the location and extent of the involved biliary duct than MRCP and ERCP[13]. In our case, CT revealed two well-defined masses in the ampulla of Vater. The radiological finding of a polypous mass with a long pedicle was helpful to diagnose an adenoma. The ampullary small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma presented as a well-enhancing mass with local lymphadenopathy and differentiating it from ampullary adenocarcinoma may not be possible. Thus, small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma should be included in the differential diagnosis of ampullary masses especially when the patient is an elderly man.

| 1. | Levenson RM Jr, Ihde DC, Matthews MJ, Cohen MH, Gazdar AF, Bunn PA Jr, Minna JD. Small cell carcinoma presenting as an extrapulmonary neoplasm: sites of origin and response to chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1981;67:607-612. |

| 2. | Brenner B, Tang LH, Klimstra DS, Kelsen DP. Small-cell carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract: a review. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2730-2739. |

| 3. | Lee CS, Machet D, Rode J. Small cell carcinoma of the ampulla of vater. Cancer. 1992;70:1502-1504. |

| 4. | Yamaguchi K, Enjoji M. Adenoma of the ampulla of Vater: putative precancerous lesion. Gut. 1991;32:1558-1561. |

| 5. | Nassar H, Albores-Saavedra J, Klimstra DS. High-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ampulla of vater: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 14 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:588-594. |

| 6. | Suzuki S, Tanaka S, Hayashi T, Harada N, Suzuki M, Hanyu F, Ban S. Small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:450-453. |

| 7. | Beger HG, Thorab FC, Liu Z, Harada N, Rau BM. Pathogenesis and treatment of neoplastic diseases of the papilla of Vater: Kausch-Whipple procedure with lymph node dissection in cancer of the papilla of Vater. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2004;11:232-238. |

| 8. | Fujii H, Aotake T, Horiuchi T, Chiba Y, Imamura Y, Tanaka K. Small cell carcinoma of the gallbladder: a case report and review of 53 cases in the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1588-1593. |

| 9. | Zamboni G, Franzin G, Bonetti F, Scarpa A, Chilosi M, Colombari R, Menestrina F, Pea M, Iacono C, Serio G. Small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ampullary region. A clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study of three cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:703-713. |

| 10. | Venu RP, Geenen JE. Diagnosis and treatment of diseases of the papilla. Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;15:439-456. |

| 11. | Sugawara G, Yamaguchi A, Isogai M, Watanabe Y, Kaneoka Y, Suzuki M. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater with foci of squamous differentiation: a case report. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2004;11:56-60. |

| 12. | Cavazza A, Gallo M, Valcavi R, De Marco L, Gardini G. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ampulla of vater. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:221-223. |

| 13. | Rosch T, Meining A, Fruhmorgen S, Zillinger C, Schusdziarra V, Hellerhoff K, Classen M, Helmberger H. A prospective comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of ERCP, MRCP, CT, and EUS in biliary strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:870-876. |