INTRODUCTION

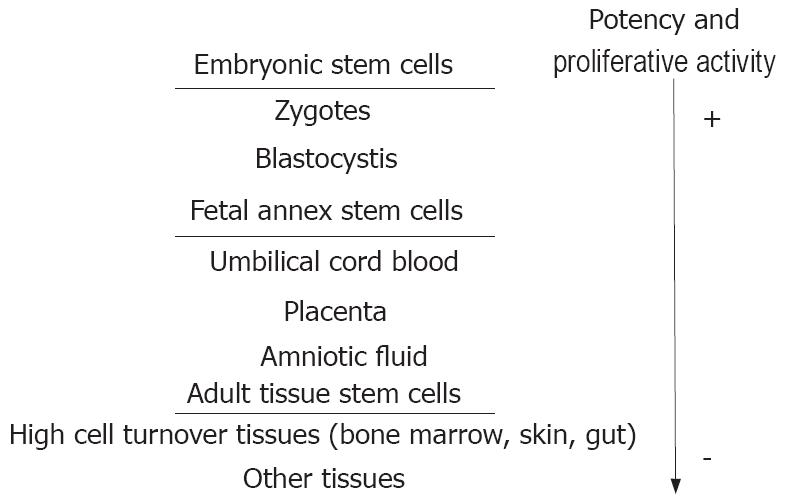

A stem cell is an undifferentiated cell capable of renewing itself throughout its life and of generating one or more types of differentiated cells. While embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are the only ones to be totipotential, adult tissues with high cellular turnover (e.g. skin, gut mucosa and bone marrow) retain a population of stem cells with restricted differentiation potential that constantly supply the tissue with new cells (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Stem cell hierarchy in humans.

While embryonic stem cells are the only ones to be totipotential, adult tissues with high cellular turnover (e.g. skin, gut mucosa and bone marrow) retain a population of stem cells with restricted differentiation potential that constantly supply the tissue of new cells.

End stage liver disease (ESLD) is the final stage of acute or chronic liver damage and is irreversibly associated with liver failure. ESLD can develop rapidly, over days or weeks (acute and sub-acute liver failure, respectively), or gradually, over months or years (chronic liver failure)[1]. Currently, liver transplantation is the most effective therapy for patients with ESLD[2]. However, its potential benefits are hampered by many drawbacks, such as the relative shortage of donors, operative risk, post-transplant rejection, recidivism of the pre-existing liver disease, and high costs.

In this scenario, stem cell therapy sounds particu-larly attractive for its potential to support tissue regeneration requiring minimally invasive procedures with few complications. This field of research, which represents the ground from which the new discipline of “regenerative medicine” has germinated, has rapidly developed in recent years, arising great interest among scientists and physicians, and frequently appearing in newspapers headlines touting miracle cures, but arising ethical crises as well[3]. The most debated issue pertains to the use of human ESCs, as it implies, with current technologies, the destruction of human embryos. Opponents of ESC research argue that ESC research represents a slippery slope to reproductive cloning, and can fundamentally devalue human life. Contrarily, supporters argue that such research should be pursued because the resultant treatments could have significant medical potential. It is also noted that excess embryos created for in vitro fertilization could be donated with consent and used for the research[4].

The ensuing debate has prompted authorities around the world to seek regulatory frameworks and highlighted the fact that stem cell research represents a social and ethical challenge. Thus, current legislation on ESC use widely varies, with some countries being more permissive (such as UK, Netherlands, Spain and France) than others (such as North America and most of the North European countries)[4].

GENERAL ISSUES

How might stem cells help?

An ongoing debate involves the mechanisms by which stem cells might restore the function of a diseased organ. While some research groups support the hypothesis of stem cell integration into the tissue through “transdifferentiation” or “fusion” with resident parenchymal cells, others favour stem cells helping local cells through soluble factors production.

How might stem cells be implanted?

The way of stem cell administration to a diseased organ widely varies in different studies, from local (direct vascular delivery) to peripheral (injection in a peripheral vein) route. Moreover, attempts to increase the number of circulating stem cells by administering growth factors have been made. Which way is best it is still unclear, and further studies are needed to clear doubts.

What is the transferability of the data obtained from animal models to human disease?

Most data come from experiments performed in rodents, in which an organ is injured, either chemically or surgically, to study the effect of subsequent stem cell administration. Whilst animal studies are quite numerous, human usage of stem cells is still far from being everyday practice, particularly in the setting of ESLD. The translation of animal data to human disease has to be taken with great caution, and the validation of basic investigations still requires further extensive research.

How far are we with stem cell purity and function and stability of their products?

The techniques for both ESC line isolation and adult stem cell separation from tissues need to be refined, since separation from stromal contaminating components is still not optimal. Moreover, although mature cells have been obtained by stem cell transdifferentiation in vitro, their ability to express the entire repertoire of specific biological functions and maintain them over time has not been clearly demonstrated as yet.

LIVER REGENERATION

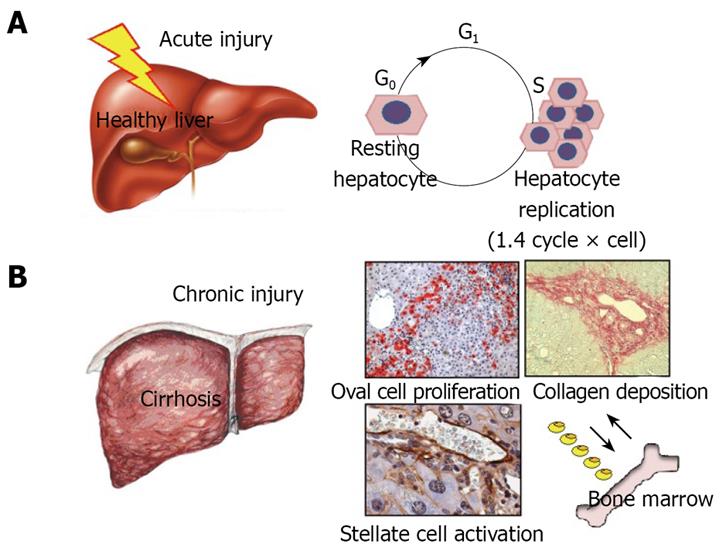

Under physiological conditions, the liver does not need any external source of cells to repair injury, as resting hepatocytes have the ability to re-enter the cell cycle rapidly and efficiently after an injury has occurred. Nevertheless, in persistent liver injury, as is the case with chronic liver diseases in humans, the sustained proliferative stress prematurely ages the hepatocytes and exhausts their ability to replicate. In this context, hepatic progenitor cells (or “oval cells”, as they are called in rodents where they were first described) appear as a rich population of small round cells spreading from the periportal area into the parenchyma[5]. Oval cells have been demonstrated to be bipotential progenitors able to generate both hepatocytes and biliary cells[6–8]. They are thought to reside in the terminal branches of the intrahepatic biliary tree (e.g. the canals of Hering)[8] and support liver regeneration when hepatocyte proliferation is ineffective in absolute or relative terms. Rodent oval cells have proved effective in repopulating the diseased liver, but a clearly positive effect on liver function has yet to be fully demonstrated. By contrast, there is evidence that, as bipotential progenitors, oval cells can give rise to both hepatocellular- and cholangio-carcinoma[9]. The lack of an exclusive oval cell marker makes this cell population elusive and this has aroused much speculation. Some years ago, the finding of CD34 and Sca-1 hematopoietic markers on oval cells gave rise to the theory of an active trafficking of stem cells between the bone marrow (BM) and the liver and a potential involvement of the BM in liver regeneration during injury[10]. Although extremely attractive, this hypothesis is the topic of ongoing debate (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Under physiological conditions, the liver does not need any external source of cells to repair injury, as resting hepatocytes have the ability to re-enter the cell cycle rapidly and efficiently after an injury has occurred (A).

In persistent liver injury, as is the case with liver cirrhosis, the sustained proliferative stress prematurely ages the hepatocytes and exhausts their ability to replicate. In this context hepatic progenitor cells, or oval cells as they are called in rodents where they were first described, appear as a rich population of small round cells spreading from the periportal area into the parenchyma. The contribution of bone marrow derived stem cells to tissue regeneration in chronic liver diseases is still debated (B).

BONE MARROW-DERIVED STEM CELLS

All the experimental strategies and conceptual paradigms applicable to stem cells in general were initially defined in haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) residing in the BM. Not being at the top of the stem cell hierarchy, HSCs were initially thought to possess a restricted differentiation potential and therefore to be able to generate only cells of the haematopoietic system. This theory was questioned after studies in BM transplanted patients demonstrated the presence of donor-derived epithelial cells in some extra-haematological tissues, including the liver[11]. The hypothesis of a “germ layer-unrestricted plasticity” of HSCs rapidly captured the attention of investigators interested in regenerative medicine. There are several potential advantages of using adult rather than embryonic stem cells to regenerate tissues including fewer ethical concerns, better known biological behaviour, easier accessibility and, therefore, lower costs.

Both rodent and human HSCs have been induced to differentiate into hepatocytes in vitro. Most of the protocols to induce CD34+ HSCs differentiation into hepatocytes employed growing media conditioned with growth factors and mitogens [e.g. hepatocyte growth factors (HGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and oncostatin M] and culture layers specific for hepatocyte growth, like matrigel. To reproduce the pathophysiological conditions of liver injury, some studies also employed cholestatic serum or co-culture with chemically damaged liver tissue[12–14]. Although these studies showed some HSC “transdifferentiation” into hepatocytes, the reported percentage of hepatocytes derived from HSCs did not exceed 5%. Thus, HSCs exhibit a limited differentiation potential that make them non-optimal candidates for tissue regeneration purposes. The cost of repeated cultures needed to obtain sufficient amounts of hepatocytes from HSC would presumably be too high for cell therapy-based applications.

Another population of stem cells in adults resides in the bone marrow stroma. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMMSCs), as they are termed, represent the non-haematopoietic fraction of the bone marrow. In vitro, they are adherent, clonogenic, non-phagocytic and fibroblastic in habit. Under proper experimental conditions, they are able to differentiate into bone, cartilage, adipose and fibrous tissue, and hematopoietic supporting tissue[14]. There is also evidence that BMMSCs can undergo unorthodox differentiation, giving rise to cells with visceral mesoderm, neuroectoderm and endoderm characteristics. When transplanted, these cells can engraft in bone, muscle, brain, lung, heart, liver, gastrointestinal tract and haematopoietic tissue, and could even contribute to most somatic cell types when injected into an early blastocyst[15]. In vitro experiments have shown that human and rodent BMMSCs grown on matrigel and supplemented with HGF and FGF-4 differentiate into mature hepatocytes, with a differentiation rate ranging from 30% to 80%[1617]. BMMSCs that acquire the hepatocyte phenotype in vitro[18] also exhibit typical hepatocyte functions, including albumin production, glycogen storage, urea secretion, low density-lipoprotein uptake and phenobarbital-inducible cytochrome-P450 activity. BMMSCs likely represent pluripotent stem cells that remain in adult life and experimental evidence suggests that they might be a reliable cellular source to generate hepatocytes for use in cell therapy.

Flanking in vitro experiments, in vivo tests with BM-derived stem cells have also been performed to treat the diseased liver. Most data have been obtained in rodent models where liver damage was induced by either a hepatospecific necrotic insult (e.g. carbon tetrachloride (CCl4), allyl-alcohol or fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase (FAH) genetically induced deficiency) or a proliferative stimulus like partial hepatectomy and bile duct legation. Retrorsine or 2-acetyl-aminofluorene, two liver toxins enhancing oval/progenitor cell proliferation, have frequently been used to simulate chronic liver damage[19–22]. Another model of chronic hepatocellular injury used to study the role of BM in liver regeneration is the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) transgenic mouse model[23].

The results obtained in rodents have frequently been puzzling. What generally emerges is that BMSC engraftment into the damaged liver widely varies, ranging from 0.16% to about 50% in different experiments[24–27]. Even though the cellular mechanisms responsible for these variable results are not known, transdifferentiation into hepatocytes occurs at a very low level when CD34+ HSCs are administered to rodents treated with liver toxins[28]. On the other hand, cell fusion between hepatocytes and stem cells from the myelomonocytic lineage of the BM (e.g. the precursors of circulating macrophages) has been shown to underlie liver regeneration after BM administration in the FAH-deficient mouse[2021]. A genetic advantage of the transplanted BM stem cells with respect to resident enzyme-deficient hepatocytes likely accounts for the higher level of engraftment and tissue repopulation observed in this model.

Whereas hepatocyte formation from BM cells in vivo has proved to be poorly effective, some studies have postulated a much more important role for BM derived stem cells in liver tissue remodelling and fibrosis resolution. In mice injured with CCl4 and thioacetamide, Russo et al[29] demonstrated that the BM-derived stem cell contribution to parenchymal regeneration was marginal (0.6%), but they substantially contributed to hepatic stellate cell (68%) and myofibroblast (70%) populations, which were able to influence the liver fibrotic response to toxin injury. In a sex-mismatched bone marrow transplantation model, both stellate cells and myofibroblasts of donor origin found in the recipient liver did not originate through cell fusion with the indigenous hepatocytes, but largely derived from the circulating BMMSCs[29]. Lastly, Duffield et al[30] showed in rodents that BM-derived macrophages are likely to be crucial in regulating the liver fibrotic response to injury in a time-dependent manner, since depletion of these cells before injury reduces the fibrotic response, whereas their depletion during the recovery phase is associated with a greater fibrosis.

In contrast to the many studies performed in animals, those on BM-derived stem cell administration to patients with liver diseases can be counted on one hand. They can be divided into studies performed in patients with and without an underlying chronic liver disease. In patients with liver malignancies arisen on a “healthy” liver, the intraportal injection of CD133+ BM stem cells (a subpopulation of stem cells with both haematopoietic and endothelial progenitor characteristics) improved liver regeneration after extensive resection and segmental portal vein embolization[31]. This procedure was safe and highly effective in terms of liver mass recovery. Looking at future applications, this technique may offer the chance to treat the so-called “small-for-size” liver failure, a dramatic event occurring in transplanted patients who received either a small or a split liver. Few studies dealing with stem cell therapy in patients with liver cirrhosis[32–34] have been published to date. Gordon et al[32] injected CD34+ HSCs directly into the liver vascular system of patients with cirrhosis, whereas Terai et al[32] injected autologous BM through a peripheral vein. Albeit the small number of patients and lack of a control group[34], both studies demonstrated a slight improvement in liver function and clinical conditions. These results seem to confirm, at least in part, the results obtained in the many experiments performed in rodents showing some role of BM-derived stem cells in liver repair. In our experience[35], the administration of granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) to mobilize BM-stem cells to the peripheral blood did not modify the residual liver function in patients with compensated liver cirrhosis. However, the procedure was safe, and may represent a good way to obtain autologous stem cells for cell therapy applications.

EMBRYONIC STEM CELLS

Due to the difficulty in controlling their huge proliferative and differentiative potential, and major ethical concerns, the use of human ESCs is currently limited to in vitro and animal studies. Biotechnology industries and research laboratories are committed to devise effective protocols to optimize the ability of ESCs to differentiate into functional hepatocytes. The final goal is relevant on both scientific and clinical grounds. A suitable source of hepatocytes is what is lacking for the implementation of bio-artificial liver (BAL) technology. Effective protocols are needed not only to promote ESC differentiation into hepatocytes, but also to determine the expression of hepatic functions such as albumin secretion, indocyanine green uptake and release, glycogen storage and p450 metabolism[36].

Cytokines and growth factors such as HGF and FGF have been shown to promote ESC differentiation and growth[37]. In addition, it has been demonstrated that sodium butyrate, a non-proteinaceous compound, supports the action of these factors[38]. Hay et al[39] developed a multistage system in which HGF was used without the requirement of sodium butyrate, and human ESCs differentiated into hepatocyte-like cells without embryoid body formation. Use of an extracellular synthetic or natural matrix can be relevant, as shown by Ishizaka et al[40] in a three-dimensional system in which hepatocytes developed from mouse ESCs transfected with the hepatocyte nuclear factor-3 beta on a 3-D matrix scaffold. 3-D matrix scaffolds have been reported to be superior to the more commonly used 2-D monolayer culture in inducing differentiation into hepatocytes[41]. This is not surprising, as 3-D matrix scaffolds better reproduce the architecture of the liver parenchyma, which is essential for normal tissue function.

Another effective way to obtain hepatic differen-tiation is genetic modulation. This can be achieved by transfecting stem cells with recombinant DNA encoding for hepatospecific proteins. Adding collagen, appropriate cytokines and growth factors has an important effect on hepatocyte differentiation[42]. Recently Agarwal et al[43] proposed a new differentiation protocol for the generation of high-purity (70%) hepatocyte cultures: the differentiation process was largely uniform, with cell cultures progressively expressing increasing numbers of hepatic lineage markers and functional hepatic characteristics. When transplanted in mice with acute liver injury, the human ESC derived endoderm differentiated into hepatocytes and repopulated the damaged liver.

FETAL ANNEX STEM CELLS

Cord blood contains multiple populations of embryonic-like and other pluripotential stem cells capable of originating hematopoietic, epithelial, endothelial, and neural tissues both in vitro and in vivo. The isolation of HSCs and MSCs from cord blood is a relatively new procedure and only few studies have been published[4445].

Sàez-Lara et al[46] transplanted CD34+ HSCs derived from human cord blood into rats with liver cirrhosis without achieving a significant rate of engraftment, as GFP-positive cells were clearly eliminated. By contrast[47], low-density mononuclear cells obtained from human cord blood transplanted in utero in fetal rats generated functional hepatocytes that persisted in the fetal recipient liver at least 6 months after birth. This humanized animal model provides a very interesting approach to in vivo investigation of human cord blood stem cell differentiation into hepatocytes. Hong et al[48] described the ability of human umbilical cord blood MSCs (CD34-) to differentiate into hepatocytes when cultured in pro-hepatogenic conditions. The differentiation rate in their protocol was about 50%, and the hepatocytes obtained were capable of incorporating low-density lipoprotein, considered one of the most typical hepatocyte functions. More recently, Campard et al[49] demonstrated that human cord matrix stem cells cultured with growth factors show hepatocyte characteristics like cytochrome P450-34A expression, glycogen storage and urea production. In addition, when transplanted into hepatectomized immune-deficient mice, small clusters of human cells expressing albumin and alpha-fetoprotein appear, thereby demonstrating the good engraftment and differentiation capacity of the transplanted cells[5051].

Placenta is another potential source of stem cells. Placenta-derived stem cells (PDSCs) are fibroblast-like cells that attach to a plastic surface. Like BMMSCs, they can be expanded for more than 20 population doublings and induced to differentiate into cells of various mesenchymal tissues. Chien et al[52] recently cultivated PDSCs derived from human placentae in hepatic differentiation media, and obtained cells with hepatocyte morphology expressing specific hepatocyte functions. In comparison with stem cells isolated from other tissues there are no ethical problems associated with the study of PDSCs as the collection of placenta samples does not harm mother or infant. The ability of PDSCs to differentiate and their straightforward handling could make them an appropriate source for cell-based applications.

CONCLUSION

Under proper experimental conditions, adult, embryonic and fetal annex stem cells have been shown to be able to differentiate into hepatocytes. At present, most biotechnology industries and research laboratories are working to optimize the differentiation protocols. In the future, stem cell-derived hepatocytes will likely be used in BAL employed as “bridge therapy” for patients with liver failure awaiting transplantation or to recover liver function. Intrahepatic injection of stem cell-derived hepatocytes might also be useful in patients with acute liver failure.

In chronic liver diseases, which account for the majority of cases of liver failure worldwide, the future of stem cell therapy is still uncertain. Liver failure occurring in patients with chronic liver disease, namely cirrhosis, is not only due to the lack of healthy cells, but also to the disruption of tissue architecture and progressive accumulation of inflammatory cells and fibrosis. While “brand new” hepatocytes derived from stem cells may temporarily support the impaired liver function, they would hardly be able to restore the original liver structure and eliminate collagen deposition. Thus, further strategies are needed. A better understanding of the mechanisms leading to collagen deposition and re-adsorption, and the development of new antifibrotic agents, combined with effective antiviral agents for patients with viral hepatitis, will be critical for the success of cell-based therapy in chronic liver failure.

Supported by The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) Sheila Sherlock Post-Doc Fellowship and by “Ordine dei Medici Chirurghi ed Odontoiatri di Bologna” (SL).