Published online Sep 21, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i35.4776

Revised: June 13, 2007

Accepted: June 18, 2007

Published online: September 21, 2007

AIM: To investigate the distribution pathway of metastatic lymph nodes in gastric carcinoma as a foundation for rational lymphadenectomy.

METHODS: We investigated 173 cases with solitary or single station metastatic lymph nodes (LN) from among 2476 gastric carcinoma patients. The location of metastatic LN, histological type and growth patterns were analyzed retrospectively.

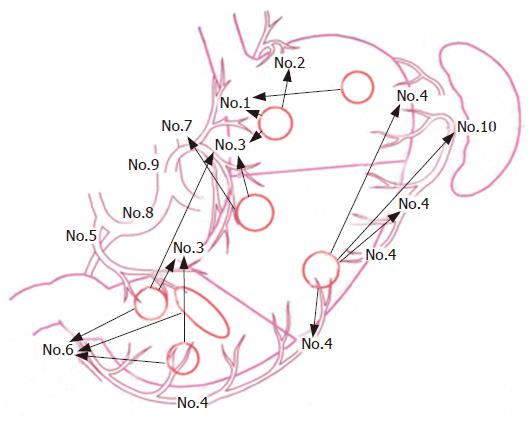

RESULTS: Of 88 solitary node metastases cases, 65 were limited to perigastric nodes (N1), while 23 showed skipping metastasis. Among 8 tumors in the upper third stomach, 3 involved right paracardial LN (station number: No.1), and one in the greater curvature was found in No.1. In the 28 middle third stomach tumors, 10 were found in LN of the lesser curvature (No.3) and 6 in LN of the left gastric artery (No.7); 5 of the 20 cases on the lesser curvature spread to No.7, while 2 of the 8 on the greater curvature metastasized to LN of the spleen hilum (No.10). Of 52 lower third stomach tumors, 13 involved in No.3 and 19 were detected in inferior pyloric LN (No.6); 9 of the 29 cases along the lesser curvature were involved in No.6.

CONCLUSION: Transversal and skipping metastases of sentinel lymph nodes (SLN) are notable, and rational lymphadenectomy should, therefore, be performed.

- Citation: Liu CG, Lu P, Lu Y, Jin F, Xu HM, Wang SB, Chen JQ. Distribution of solitary lymph nodes in primary gastric cancer: A retrospective study and clinical implications. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(35): 4776-4780

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i35/4776.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i35.4776

Lymphatic metastasis is the most important factor for prognosis of gastric carcinoma. To avoid missing positive lymph nodes, surgeons have performed an extensive radical lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer, a method which is also used when early tumors are present. As a result, patients that did not have lymph node metastasis have had to undergo operations and face potentially avoidable risks[1,2].

As the SLN concept gains acceptance, onco-surgery researchers are optimistic that the concept may serve as a breakthrough management tool to be used in gastric cancer; however, the concept is still considered to be at an investigative stage[3]. We studied the distribution pathway of solitary or positive lymph nodes limited to a single station to provide a foundation for undertaking rational lymphadenectomy for gastric carcinoma.

One hundred and seventy-three patients were selected from the 2476 patients with gastric cancer for whom radical operations were performed at the first affiliated hospital of the China Medical University between 1980 and 2003. The criteria used for inclusion was: (1) D2 lymph node dissections had been performed[4]; (2) there were greater than 15 lymph nodes, and the resected specimens had been analyzed pathologically[5]; (3) patients with pT4 and M1 stage were excluded[5]; (4) patients’ medical records were complete. Among the 173 cases, 88 had solitary lymph metastasis and 85 involved a single station lymph node. Sixty-four of the 88 patients were male and 24 female. The average age of the patients in this group was 57.6 ± 7.2 years (range 30-80). With respect to tumor location, the tumor was found in the upper third stomach area (U) in 8 cases, in the middle third (M) in 28, and in the lower third (L) in 52. Amongst the 85 patients with single station node metastasis, 60 were male and 25 female. The average age of the patients in this group was 58.2 ± 8.3 years (range 32-76). In respect of tumor location; the tumor was in the U in 23 cases, in the M in 12, and in the L stomach areas in 50.

The location of the tumor, the classification of the lymph node and histological type were by the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma[6]. For classification, the symbol “No.” indicates lymph node station number and “N” indicates the lymph node group. The histological types included differentiated and undifferentiated. An “adjacent metastasis” was defined as when lymph node metastasis is limited to the tumor side of N1; “transversal metastasis” is limited to the region of N1 opposite the tumor; and a “skipping metastasis” indicates a lymph node metastasized outside of N1.

Histological growth patterns included massive, nest, and diffuse types[7].

All data were analyzed using SPSS13.0 statistics software. The differences of the frequency distributions between the two groups of lymph nodes were determined by a χ2-test or by Fisher’s exact test. A χ2-test was adopted in the analysis of a single factor and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Among the 88 patients with a solitary metastatic lymph node, in 65 (73.9%) the lymph nodes involved were within N1, and 23 (26.1%) were over N1. In 8 cases the tumor was in the U location, amongst which 6 (75%)were observed to be in N1 and 2 (25%) in N2. In 28 cases the tumor was in the M region, amongst which 19 (67.9%) were involved in N1 and 9 (32.1%) in N2. Among the 52 patients with L region cancers, 40 were found with solitary metastatic nodes in N1, 10 (19.2%) with nodes in N2 and 2 (3.9%) in N3 (Table 1).

Comparisons were also made between cases with a solitary metastasis lymph node and single station nodes. No statistically significant difference was found with respect to the distribution of metastatic lymph nodes in the U, M and L regions using a χ2-test or Fisher’s exact test (Table 1).

In 7 of the 8 cases with a U region tumor, the tumor located at the side of the lesser curvature region. Amongst them, metastatic lymph nodes in 2 (28.6%) were detected within No.1. Among the 28 cases with a tumor in the M area, in 20 the tumor was observed in the lesser curvature region and in 8 in the greater curvature region. Metastatic lymph nodes in 10 of the 20 cases were found within No. 3, while 3 of the 8 were within No. 4.

Fifty-two cases had tumors in the L stomach area. Amongst these the tumors in 29 located at the lesser curvature region, 15 at the greater curvature side and 8 extended in a circle. Metastatic lymph nodes in 9 of the 29 cases were found within No.3, in 7 of the 15 within No.6, and in 3 of the 8 within No. 6 (Table 2 and Figure 1).

There was just one case with a tumor in the U area, and solitary metastatic lymph nodes were found within No.1. Twenty-nine patients had tumors at the lesser curvature side in the L area, and 9 (31%) of them were found to have metastatic lymph nodes within No.6. Of the 15 cases with tumors at the greater curvature side, in the L stomach area, 3 (20%) were involved in No.3 (Table 2 and Figure 1).

Among the 8 cases with tumors in the U area of the lesser curvature region, one solitary metastatic lymph node (14.3% of total) was observed within No.7, and another node (14.3%) was found within No.8. In the M area, 5 (25%) of the 20 patients who had tumors at the lesser curvature side had metastatic lymph nodes within No.7, while a metastatic node was detected within No.10 in 2 (25%) of the 8 patients with a tumor in the greater curvature side. Among the 29 cases with a tumor in area L, the number of lymph node metastases involved in No.1, No.7 and No.8 were 2 (6.9%), 2 (6.9%) and 3 (10.3%), respectively (Table 2 and Figure 1).

Comparing the 65 patients with metastasis within N1 and the 23 with a skipping metastasis, no statistical significance was found between histological type and the growth patterns of the two groups (Tables 3 and 4). Also, there was no significant difference between the adjacent metastasis group (39) and the transversal metastasis group (20) (Tables 5 and 6).

| Group N1 | Group > N1 | P value | |

| L tumors | 0.192 | ||

| Differentiated | 22 | 4 | |

| Undifferentiated | 18 | 8 | |

| M tumors | 0.299 | ||

| Differentiated | 3 | 3 | |

| Undifferentiated | 16 | 6 | |

| U tumors | 1.000 | ||

| Differentiated | 3 | 1 | |

| Undifferentiated | 3 | 1 | |

| Total | 0.489 | ||

| Differentiated | 28 | 8 | |

| Undifferentiated | 37 | 15 |

| Group N1 | Group > N1 | P values | |

| L tumors | 0.087 | ||

| Massive | 8 | 3 | |

| Nest | 21 | 3 | |

| Diffuse | 11 | 6 | |

| M tumors | 0.456 | ||

| Massive | 2 | 2 | |

| Nest | 8 | 2 | |

| Diffuse | 9 | 5 | |

| U tumors | 0.645 | ||

| Massive | 1 | 1 | |

| Nest | 2 | 0 | |

| Diffuse | 3 | 1 | |

| TOTAL | 0.051 | ||

| Massive | 11 | 6 | |

| Nest | 31 | 5 | |

| Diffuse | 23 | 12 |

There is little clinical literature available on the lymphatic routes of the stomach[8-10]. After analyzing 51 cases, Kosaka et al[11] reported that 44 gastric carcinomas with solitary lymph node metastasis were involved within N1. Ichikura et al[12] analyzed 69 cases with solitary lymph node metastasis, and found that in 6 of the 28 cases that had a lesion along the lesser curvature region, lymph node metastasis was observed along the greater curvature region. Kikuchi[13] reported that skipping metastasis occurred in 14% of their patients with a solitary lymph node.

We investigated 173 cases with a solitary or single station metastatic lymph node from 2476 gastric cancer patients. First, 74.2% of the solitary metastasis lymph nodes were limited to within N1. The lesion found in each region had one or more adjacent lymph node stations where a metastasis was more frequently found. These lymph node stations were relatively certain for the lesion in each region. Second, the frequency of transversal lymph node metastases, referring to the lesion in each region, was also relatively high. For example, with reference to a lesion in the L region, 31% of patients with a primary tumor on the lesser curvature area involved No.6, while 20% with a lesion on the greater curvature involved No.3. Third, the frequency of skipping metastases in our study was 25.8%. The frequencies of metastases in N2 in regions U, M and L were 25%, 32.1% and 19.2%, respectively. We noted that the frequency of skipping metastasis in region M was 25%, that is, 25% of the lesions at the lesser curvature side were detected in No.7 and No.8, and 25% of the lesions at the greater curvature were found in No.10.

From the above results, it is apparent that the distribution patterns of solitary nodes in gastric carcinoma are basically adjacent metastases; however, transversal and skipping metastasis were also found. The histological type and growth patterns did not influence the distribution of solitary metastatic nodes.

The first possible nodes of metastasis along the route of lymphatic drainage from the primary lesion should be SLN[14]. However, because of the multidirectional and complicated lymphatic flow from the GI tract, when using methods that inject dyes or radioactive tracers, there is likely to be some bias in the description of the distribution pathway of SLN in gastric carcinoma[15-17]. By analyzing the location of solitary metastatic lymph nodes, the distribution pathway of SLN in gastric carcinoma can be accurately assessed.

After analyzing the clinical records of 51 patients with solitary lymph node metastasis, Kosaka et al[11] reported 7 cases of lymph node metastases in N2-N3 without being in N1. Kosaka et al[11] suggested that the following could have a role in skipping metastasis: (1) occult metastases may remain unseen in a routine histopathological examination; (2) there may be a great number of lymphatic routes in the minor omentum; and (3) there may have been only a few perigastric nodes in those cases.

In this study, transversal and skipping metastasis were found to be notable. However, to date the reasons for the occurrence of skipping metastasis remain poorly understood. Chen et al[18] studied the dynamic role of stomach lymphatic flow from 138 infant corpses using 20% Prussian Blue Chloroform Solution as lymphatic dye. They reported that in 40 of 41 cases in which the drainage pointed at the greater curvature of the corpus gastricum, the lymphatic channel flowed directly to No.10. Therefore, with reference to lesions in a certain region, the so-called “skipping metastasis” of a SLN may be the first lymph node in the lymphatic drainage system. In cases where metastasis first occurs in N2 or N3, the function of N2 or N3 is considered to be the same as N1[14].

In the past 23 years, 2476 patients with gastric cancer were treated at our hospital. Among them, for the 728 patients without metastatic lymph nodes an extended D1 dissection was also performed, and as a result some cases had complications connected with the dissection. A great achievement of gastric surgeons in the last century, one that deserves unequivocal respect, has been to establish radical surgery with extensive lymph node dissection for gastric cancer. However, we now need to proceed to another stage by improving post-operative function and quality of life after gastric cancer surgery without impairing long-term outcomes[19,20]. The concept of a “minimally invasive, curative, safe operation” has gradually gained acceptance[21,22]. Here, we have attempted to discover the distribution pathway of SLN in order to provide clinical data for rational lymphadenectomy.

Based on the study we suggest that: (1) for patients with U area cancer at the lesser curvature region, No.7 and No.8 should be treated in the same way as N1; (2) for patients with cancer in the M area in the lesser curvature region, No.7 should be treated in the same was as N1; (3) for patients with cancer in the M area at the greater curvature region, No.10 should be inspected more carefully, although No.10 can be regarded as the same as N3 for an M area cancer[6]; further, if No.10 is questionable, a resection of the spleen should be undertaken[4]; and 4) for patients with cancer in the L area at the lesser curvature region, No.1, No.7 and No.8 should be inspected more carefully.

The first possible nodes of metastasis along the route of lymphatic drainage from the primary lesion should be a sentinel lymph node (SLN). If a SLN is negative, patients can be considered to be without lymph node metastasis, and should not have to endure possible operations and face avoidable risks. The SLN concept is gaining greater acceptance, and thus clinicians and researchers can be optimistic that it may serve as a breakthrough management tool for use in gastric cancer.

Many clinicians and researchers are presently undertaking studies of the distribution pathway of SLN in gastric carcinoma. However, because of the multidirectional and complicated lymphatic flow from the GI tract, there is likely to be some bias in the description of the distribution pathway of SLN in gastric carcinoma when using methods that inject dyes or radioactive tracers. The first possible sites of metastasis along the route of lymphatic drainage from the primary lesion are known as SLN. Therefore, a solitary metastatic lymph node could be regarded as SLN in gastric carcinoma. Some onco-surgery scholars have attempted to assess the distribution pathway of SLN in gastric carcinoma by analyzing the location of solitary metastatic lymph nodes.

Based on a large sample study, we described the distribution pathway of solitary metastatic lymph nodes and put forward concrete suggestions for lymph node dissection in gastric cancer.

We attempted to discover the distribution pathway of solitary metastatic lymph nodes in gastric cancer. Our results provide clinical data for rational lymphadenectomy and for experimental study of SLN.

Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) is well recognized; however, rational lymphadenectomy operations are more focused on in this study. MIS is more about treatment of early gastric cancer, while rational lymphadenectomy is more about advanced gastric cancer.

This manuscript presents a good overview of the distribution of lymph node metastasis in gastric cancer and should be of interest to GI researchers and clinicians.

Supported in part by the Gastric Cancer Laboratory of Chinese Medical University

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor McGowan D E- Editor Liu Y

| 1. | Yoshikawa T, Tsuburaya A, Kobayashi O, Sairenji M, Motohashi H, Noguchi Y. Is D2 lymph node dissection necessary for early gastric cancer? Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:401-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Adachi Y, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Modern treatment of early gastric cancer: review of the Japanese experience. Dig Surg. 2002;19:333-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kitagawa Y, Kitajima M. Sentinel node mapping for gastric cancer: is the jury still out? Gastric Cancer. 2004;7:135-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sasaki T. In regard to gastric cancer treatment guidelines--a revised edition. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2004;31:1947-1951. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Yoo CH, Noh SH, Kim YI, Min JS. Comparison of prognostic significance of nodal staging between old (4th edition) and new (5th edition) UICC TNM classification for gastric carcinoma. International Union Against Cancer. World J Surg. 1999;23:492-497; discussion 492-497;. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma. 2nd English Edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2009] [Cited by in RCA: 1942] [Article Influence: 71.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen JQ. Problems in the surgical treatment of gastric cancers. Zhonghua WaiKe ZaZhi. 1991;29:220-223, 220-223. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Sano T, Katai H, Sasako M, Maruyama K. Gastric lymphography and detection of sentinel nodes. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2000;157:253-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Isozaki H, Kimura T, Tanaka N, Satoh K, Matsumoto S, Ninomiya M, Ohsaki T, Mori M. An assessment of the feasibility of sentinel lymph node-guided surgery for gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2004;7:149-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Miyake K, Seshimo A, Kameoka S. Assessment of lymph node micrometastasis in early gastric cancer in relation to sentinel nodes. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:197-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kosaka T, Ueshige N, Sugaya J, Nakano Y, Akiyama T, Tomita F, Saito H, Kita I, Takashima S. Lymphatic routes of the stomach demonstrated by gastric carcinomas with solitary lymph node metastasis. Surg Today. 1999;29:695-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ichikura T, Morita D, Uchida T, Okura E, Majima T, Ogawa T, Mochizuki H. Sentinel node concept in gastric carcinoma. World J Surg. 2002;26:318-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kikuchi S, Kurita A, Natsuya K, Sakuramoto S, Kobayashi N, Shimao H, Kakita A. First drainage lymph node(s) in gastric cancer: analysis of the topographical pattern of lymph node metastasis in patients with pN-1 stage tumors. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:601-604. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Kitagawa Y, Fujii H, Mukai M, Kubota T, Ando N, Watanabe M, Ohgami M, Otani Y, Ozawa S, Hasegawa H. The role of the sentinel lymph node in gastrointestinal cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2000;80:1799-1809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Aikou T, Kitagawa Y, Kitajima M, Uenosono Y, Bilchik AJ, Martinez SR, Saha S. Sentinel lymph node mapping with GI cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:269-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tsioulias GJ, Wood TF, Morton DL, Bilchik AJ. Lymphatic mapping and focused analysis of sentinel lymph nodes upstage gastrointestinal neoplasms. Arch Surg. 2000;135:926-932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lee JH, Ryu KW, Kim CG, Kim SK, Lee JS, Kook MC, Choi IJ, Kim YW, Chang HJ, Bae JM. Sentinel node biopsy using dye and isotope double tracers in early gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1168-1174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chen GL, Xue YW, Zhang QF, Pang D. To decide the range of stomach resection in gastric cancer radical operation according to the dynamic rule of stomach lymphatic flowing. Chin J Clin Onco. 2002;29:319-321. |

| 19. | Cuschieri A, Weeden S, Fielding J, Bancewicz J, Craven J, Joypaul V, Sydes M, Fayers P. Patient survival after D1 and D2 resections for gastric cancer: long-term results of the MRC randomized surgical trial. Surgical Co-operative Group. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1522-1530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 994] [Cited by in RCA: 996] [Article Influence: 38.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Nashimoto A, Yabusaki H, Nakagawa S. Evaluation and problems of follow-up surveillance after curative gastric cancer surgery. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 2007;108:120-124. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Hosono S, Ohtani H, Arimoto Y, Kanamiya Y. Endoscopic stenting versus surgical gastroenterostomy for palliation of malignant gastroduodenal obstruction: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:283-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hosono S, Arimoto Y, Ohtani H, Kanamiya Y. Meta-analysis of short-term outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7676-7683. [PubMed] |