Published online Dec 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i45.7304

Revised: July 28, 2006

Accepted: August 29, 2006

Published online: December 7, 2006

AIM: To relate the endoscopic findings in patients with hematochezia with regard to age in “low and average risk” for colorectal cancer (CRC) and to localize significant lesions in order to identify patients who need sigmoidoscopy or total colonoscopy.

METHODS: This prospective study was performed in an open access GI endoscopy unit. Out of 4322 consecutive patients undergoing colonoscopy, 918 reported hematochezia. The final study group comprized 180 patients aged below 45 and 237 over 45. Main exclusion criteria were a 1st-degree family history of colorectal carcinoma, patients reporting blood mixed with stools and/or progressive colonic symptoms, or patients who had undergone colon surgery for neoplastic lesions.

RESULTS: Total colonoscopy could be performed in 96% of patients. Abnormal findings were observed in 34.3% of the younger and in 65.7% of the older ones. Findings were the presence of polyps in the distal colon (n = 2) and IBD in the proximal colon (n = 29) in the group of the younger patients, and polyps (n = 15), IBD (n = 13), and carcinoma (n = 6, 4 of the lesions were located proximal to the splenic flexure) in the elderly. Our findings suggest that the diagnostic potential of total colonoscopy in patients younger than 45 referring scant hematochezia, is not mandatory. By exploring only the distal tract of the colon we have misdiagnosed two cases of IBD located in the ascending colon. In this group of patients additional risk factors must be identified before performing a total colonoscopy. Regarding the patients older than 45 yr, the exploration of the distal colon would have led to our overlooking a carcinoma, two neoplastic polyps and one IBD located in the proximal colon.

CONCLUSION: Young patients with scant hematochezia but without risk factors for neoplasia do not need a total colonoscopy, whereas is mandatory performing a total colonoscopy in older patients even in the presence of anal pathology.

- Citation: Carlo P, Paolo RF, Carmelo B, Salvatore I, Giuseppe A, Giacomo B, Antonio R. Colonoscopic evaluation of hematochezia in low and average risk patients for colorectal cancer: A prospective study. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(45): 7304-7308

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i45/7304.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i45.7304

Hematochezia defined as a chronic intermittent passage of a small amount of bright red blood from the rectum is a clinical problem frequently found in adults of all ages. Its prevalence in the apparently healthy general population is between 9% and 19%[1-5] and in general practice this means 6 consultations every 1000 over 45-year-olds a month[6]. Almost 20% of colonoscopies are prompted by rectal bleeding[7,8].

In addition to its high prevalence, hematochezia is a symptom to be considered carefully, since it is known to be associated also with neoplastic diseases (adenoma, cancer). Studies showed that 7%-10% of patients with chronic overt rectal bleeding did in fact have a colorectal cancer[5-7].

Since neoplastic and non neoplastic diseases may also coexist, a complete diagnostic work-up is indicated including clinical evaluation (clinical history, physical examination of the anal region, digital anorectal exploration), anoscopy, and endoscopic evaluation of the colon. It is a source of controversy as to whether scant hematochezia necessitates total colonoscopy as a first-line procedure or a 60 cm flexible sigmoidoscopy[9-18].

The aims of this study were: (1) to identify the type and prevalence of endoscopic findings in two groups of patients with hematochezia alone aged under vs over 45 years old; (2) to ascertain the distal (rectum, sigmoid, descending colon) or proximal (transverse and ascending colon) location of “significant lesions” in order to establish which patients need total colonoscopy.

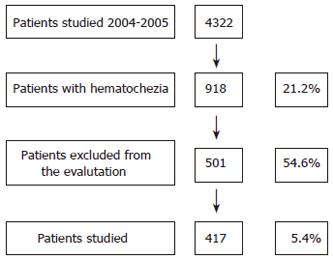

The study was performed prospectively on 4322 consecutive out-patients undergoing colonoscopy during a two-year period (November 2004-October 2005) at the “open access” Unit of Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy at University of Catania, in eastern Sicily-Italy (Figure 1).

Before colonoscopy all patients were asked about the colour of the expelled blood, the frequency and duration of the bleeding episode, and how the blood appeared (on stools, on toilet paper, on the toilet, or mixed with stools).

Exclusion criteria were age below 18 years, positive 1st-degree family history of CRC, patients reporting blood mixed with stools, and those whose bleeding was severe enough to require transfusion or hospitalization, patients who reported progressive colonic symptoms, those who had undergone colon surgery for neoplastic lesions, and those who had already had a colonoscopy within the previous year.

After clinical evaluation, all patients underwent anal inspection and anoscopy. Regardless of any anal patho-logies detected, all patients underwent total colonoscopy. Endoscopy was performed by 5 expert endoscopists (> 5000 colonoscopies) in patients after the ingestion of 4 litres of polyethylene glycol solution.

The endoscopic evaluation was considered complete when the entire colonic mucosa was visualized. Patients whose colon had been inadequately cleansed and cases in which anatomical or technical problems had prevented a complete exploration of the colon were excluded. Endoscopic findings were classified as normal, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), neoplastic disease (adenoma and carcinoma), diverticulosis, or angiodysplasia.

Neoplastic polyps > 10 mm, colorectal carcinoma, and colitis were defined as “significant lesions”. The pathologies identified were classified as proximal (situated in the transverse and/or ascending colon) and distal (between the rectum and the splenic flexure). The numerical values obtained are expressed as a percentage and the two groups of values were compared using the chi-square test and the Fisher’s exact test; a value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

From 4322 patients who underwent colonoscopy over a two-year period, the indication was hematochezia in 918 cases (21.2%), and other lower digestive tract symptoms in 3404 cases (78.8%).

From 918 patients with hematochezia, 417 (45.4%) met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). This study group was composed of 244 males (mean age 50.5 ± 14.6 years, range 19-93) and 173 females (mean age 51 ± 14.6 years, range 18-96) yielding a male/female ratio of 1.4:1. 43.2% of these patients (180/417) were between 18 and 45 years old, while 56.8% (237/417) were older than 45 (Table 1).

| Patients (n) | 417 |

| Men/women | 244/173 |

| Mean age (yr) | 50.5 ± 14.6 |

| Range | 18-96 |

| < 45 years old | 180 (43.2%) |

| > 45 years old | 237 (56.8%) |

Proctological examination revealed anal lesions potentially responsible for the bleeding in 265 cases (63.5%). Endoscopy was performed up to the cecum in 96.0% of the patients (417/430) with no complications worthy of note. The 13 incomplete explorations were due to poor colon cleaning (n = 7), abnormal sigmoid-descending colon length (n = 4), and low patient compliance (n = 2). The most common pathologies detected were polyps (n = 77, 18.5%), diverticular disease (n = 44, 10.5%), IBD (n = 42, 10%), and carcinoma (n = 6, 1.4%) (Table 2).

| Diagnosis | n | % |

| Anal pathology | 265 | 63.54 |

| Polyps | 77 | 18.46 |

| (< 10 mm) | 60 | 14.38 |

| (> 10 mm) | 17 | 4.07 |

| Diverticular diseases | 44 | 10.55 |

| IBD | 42 | 10.07 |

| Normal finding | 55 | 13.18 |

| Carcinomas | 6 | 1.43 |

| Angiodysplasia | 4 | 0.95 |

| Total | 493 |

Table 3 shows the endoscopic diagnoses with regard to the patients’ age. Anal lesions potentially responsible for hematochezia were seen in 57.2% of the patients (103/180) younger than 45 and in 68.4% (162/237) of the patients older than 45. This difference did not reach statistical significance (P < 0.84).

| Diagnosis | Age group (yr) | P | |||

| < 45 (n = 180) | > 45 (n = 237) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Anal pathology | 103 | 57.2 | 162 | 68.4 | < 0.05 |

| Polyps | 15 | 8.3 | 62 | 26.2 | < 0.0001 |

| Diverticular diseases | 0 | - | 44 | 18.6 | < 0.0001 |

| IBD | 29 | 6.1 | 13 | 5.5 | < 0.001 |

| Normal finding | 35 | 19.4 | 20 | 8.4 | < 0.01 |

| Carcinomas | 0 | - | 6 | 2.5 | < 0.05 |

| Angiodysplasia | 3 | 1.6 | 1 | 0.4 | NS |

Total colonoscopy revealed pathologies in 45.6% (82/180) of the younger, and in 61.6% (146/237) of the older patients.

None of the younger patients had diverticular disease, while this was found in 18.6% (44/237) of the older patients. The presence of neoplastic polyps and carcinomas was also much greater in the latter, with a statistically significant difference, particularly for carcinoma (P < 0.0002). Rectal bleeding (which has predictive value for the diagnosis of CRC) increased with age: it was 1.0 (95% CI 0.12-3.64) among patients younger than 45 vs 6.2 (95% CI 1.30-17.19) for those over 45. No carcinoma was diagnosed among the younger patients, but they had a higher prevalence of IBD (29/180, 16.1%) than the older younger ones (13/237, 5.5%)

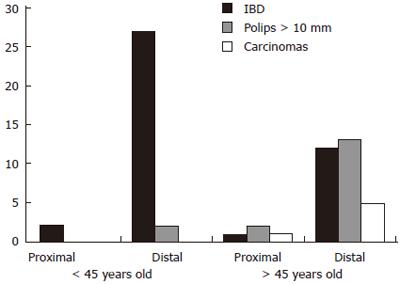

Among the 417 patients considered, 65 “significant lesions” were diagnosed in 64 patients (15.3%) (one patient had 2 lesions) including IBD (n = 42), polyps with a diameter > 10 mm (n = 17), and carcinoma (n = 6). Six of these lesions (3 cases of IBD, 2 polyps and 1 carcinoma) were located in the proximal tract of the colon and 59 (39 IBD, 15 polyps and 5 carcinomas) in the distal tract.

As for the age-related prevalence of significant lesions, the patients younger than 45 had 2 polyps > 10 mm and 29 cases (16.1%) of IBD, while the patients over 45 had 15 polyps, 13 cases (5.5%) of IBD, and 6 carcinomas (Table 4).

| Significantlesions | Age group (yr) | P | LocationProximal Distal | Tot. | ||||

| < 45 | > 45 | |||||||

| (n = 180) | (n = 237) | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | n | |||

| Polyps | 2 | 1.1 | 15 | 6.3 | < 0.05 | 1 | 16 | 17 |

| IBD | 29 | 16.1 | 13 | 5.5 | < 0.001 | 5 | 37 | 42 |

| Carcinomas | 0 | - | 6 | 2.5 | < 0.05 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Total | 31 | 34 | 7 | 58 | ||||

Figure 2 correlates the patients’ ages with the prevalence of “significant lesions” in the proximal and distal colon.

Thirty-one of the 64 patients (48.4%) with “significant lesions” were up to 45 years old and none had carcinoma. Two patients were diagnosed with polyps > 10 mm, both located in the distal colon. Twenty-nine were cases of IBD, two in the proximal colon and 27 in the left colon. Two (non neoplastic) significant lesions would have gone undiagnosed in this younger group if only flexible sigmoidoscopy had been carried out.

Thirty-four of the 64 patients (53.1%) with significant lesions were over 45 years old and included all 6 cases of carcinoma, 15 polyps > 10 mm and 13 cases of IBD. Four of these lesions (1 carcinoma, 2 polyps > 10 mm and 1 IBD) were located proximal to the left flexure and were consequently beyond the reach of flexible sigmoidoscopy (Table 4).

The passage of blood through the anus is a common symptom in adults and coincides with anal pathologies in 27%-74% of cases[16,19]. In our sample, the prevalence of anal lesions was 63.5%, with no statistically significant difference between the two age groups considered (under/over 45 years old: 57.2% vs 68.4%).

Since a large proportion of these patients only bleed from the anus, performing colonoscopy in all cases would only burden the endoscopy unit with an unjustified increase in costs. That is why numerous studies have been performed in an attempt to stratify patients at low and high risk of severe proximal colon according to their bleeding symptoms, but such analyses have produced contradictory results.

In 3 studies[16,20,21], haemorrhoid-type blood loss has rarely been associated with significant pathologies at proximal colon level, so the authors concluded that anal inspection with the rectosigmoidoscope suffices in such situations. Different conclusions were reached in three other papers finding no correlation between anal bleeding symptoms and the severity or location of colonic lesions[14,22].

Similar results were reported in a large prospective assessment that found no correlation between anal bleeding and colonic lesions: the authors concluded that total colonoscopy with a rectosigmoidoscope is always a safe, effective choice, and is also less expensive. This paper also stressed that 3 carcinomas were diagnosed in proximal colon segments among 45 patients under 45 years old[18].

Contrasting opinions are also expressed in the guidelines prepared by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and the European Panel for Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (EPAGE): while the former specify that middle-aged or older individuals must always undergo a total colonoscopy, even in the presence of an anal lesion that could justify the hematochezia[23], the latter consider total colonoscopy inappropriate when the source of bleeding has been ascertained by ano- or sigmoido-scopy[24].

When anal lesions causing bleeding are detected, the choice of investigation method should be based on the evaluation of two variables: the bleeding symptoms and the patient’s age. For hematochezia patients up to 45 years old, we believe that exploring the colon up to the left flexure is sufficient, whereas it is best to examine all of the mucosal surface in older patients[19,25-30]

It is important to remember, however, that this approach is valid for diagnosing carcinoma, but could overbook up to 7% of other, equally significant pathologies[27]. Our findings suggest that the diagnostic potential of total colonoscopy is low in population up to 45-year-old referring scant hematochezia. By exploring only the distal tract of the colon, we have misdiagnosed two case of IBD located in the ascending colon. In patients under 40 years old, additional risk factors must be identified before performing a total colonoscopy i.e. chronicity (even if it is an intermittent bleeding), the discharge of blood mixed with stools, and a 1st-degree family history of colorectal cancer. Concerning this last point, the American Cancer Society (ACS) guidelines suggest that individuals with a positive 1st-degree family history of colorectal carcinoma must undergo total colonoscopy if they are 45 or older, irrespective of any presence or absence of lower digestive tract symptoms[31]. As regard as patients over 45 years endoscopic exploration of the whole colon is indicated even is a distal cause of the bleeding was ascertained.

In the older group of patients, the exploration of the distal colon alone would have led to our overlooking a carcinoma and a neoplastic polyp (> 10 mm) both located in the hepatic flexure. In conclusion, the diagnostic algorithm to adopt in the case of hematochezia can be as follows:

- total colonoscopy is always warranted for patients older than 45 years;

- for patients younger than 45 with no risk factors (e.g. discharge of blood mixed with stools, positive 1st-degree family history of colorectal carcinoma, or clinical history of progressive colorectal disease), rectosigmoidoscopy is initially sufficient. The work-up should be completed with a total colonoscopy in cases of haemorrhage during follow-up despite the site of bleeding having been identified and a suitable therapy implemented.

Such guidelines are justified by the fact that significant lesions can occur, albeit rarely, even in the proximal colon of young adults with a negative family history for colorectal cancer. Failing to consider such a hypothesis has devastating clinical consequences for the patient and also exposes the family physician and specialist to medico-legal consequences.

In the USA, the majority of lawsuits for malpractice have to do with the misdiagnosis of colorectal carcino-mas[5,9].

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Mihm S E- Editor Liu WF

| 1. | Dent OF, Goulston KJ, Zubrzycki J, Chapuis PH. Bowel symptoms in an apparently well population. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29:243-247. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 71] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Crosland A, Jones R. Rectal bleeding: prevalence and consultation behaviour. BMJ. 1995;311:486-488. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 96] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Silman AJ, Mitchell P, Nicholls RJ, Macrae FA, Leicester RJ, Bartram CI, Simmons MJ, Campbell PD, Hearn CE, Constable PJ. Self-reported dark red bleeding as a marker comparable with occult blood testing in screening for large bowel neoplasms. Br J Surg. 1983;70:721-724. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wauters H, Van Casteren V, Buntinx F. Rectal bleeding and colorectal cancer in general practice: diagnostic study. BMJ. 2000;321:998-999. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sharma VK, Vasudeva R, Howden CW. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance practices by primary care physicians: results of a national survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1551-1556. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Metcalf JV, Smith J, Jones R, Record CO. Incidence and causes of rectal bleeding in general practice as detected by colonoscopy. Br J Gen Pract. 1996;46:161-164. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Lieberman DA, De Garmo PL, Fleischer DE, Eisen GM, Helfand M. Patterns of endoscopy use in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:619-624. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 78] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fasoli R, Repaci G, Comin U, Minoli G. A multi-centre North Italian prospective survey on some quality parameters in lower gastrointestinal endoscopy. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34:833-841. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bond JH. Rectal bleeding: is it always an indication for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:223-225. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Acosta JA, Fournier TK, Knutson CO, Ragland JJ. Colonoscopic evaluation of rectal bleeding in young adults. Am Surg. 1994;60:903-906. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Brenna E, Skreden K, Waldum HL, Mårvik R, Dybdahl JH, Kleveland PM, Sandvik AK, Halvorsen T, Myrvold HE, Petersen H. The benefit of colonoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1990;25:81-88. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Graham DJ, Pritchard TJ, Bloom AD. Colonoscopy for intermittent rectal bleeding: impact on patient management. J Surg Res. 1993;54:136-139. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Guillem JG, Forde KA, Treat MR, Neugut AI, Bodian CA. The impact of colonoscopy on the early detection of colonic neoplasms in patients with rectal bleeding. Ann Surg. 1987;206:606-611. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Helfand M, Marton KI, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Sox HC Jr. History of visible rectal bleeding in a primary care population. Initial assessment and 10-year follow-up. JAMA. 1997;277:44-48. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shinya H, Cwern M, Wolf G. Colonoscopic diagnosis and management of rectal bleeding. Surg Clin North Am. 1982;62:897-903. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Tedesco FJ, Waye JD, Raskin JB, Morris SJ, Greenwald RA. Colonoscopic evaluation of rectal bleeding: a study of 304 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89:907-909. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 73] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fine KD, Nelson AC, Ellington RT, Mossburg A. Comparison of the color of fecal blood with the anatomical location of gastrointestinal bleeding lesions: potential misdiagnosis using only flexible sigmoidoscopy for bright red blood per rectum. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3202-3210. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Goulston KJ, Cook I, Dent OF. How important is rectal bleeding in the diagnosis of bowel cancer and polyps. Lancet. 1986;2:261-265. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 80] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Church JM. Analysis of the colonoscopic findings in patients with rectal bleeding according to the pattern of their presenting symptoms. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:391-395. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cheung PS, Wong SK, Boey J, Lai CK. Frank rectal bleeding: a prospective study of causes in patients over the age of 40. Postgrad Med J. 1988;64:364-368. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Segal WN, Greenberg PD, Rockey DC, Cello JP, McQuaid KR. The outpatient evaluation of hematochezia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:179-182. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | The role of endoscopy in the patient with lower gastrointestinal bleeding. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:685-688. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gonvers JJ, De Bosset V, Froehlich F, Dubois RW, Burnand B, Vader JP. 8. Appropriateness of colonoscopy: hematochezia. Endoscopy. 1999;31:631-636. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Eckardt VF, Schmitt T, Kanzler G, Eckardt AJ, Bernhard G. Does scant hematochezia necessitate the performance of total colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2002;34:599-603. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Van Rosendaal GM, Sutherland LR, Verhoef MJ, Bailey RJ, Blustein PK, Lalor EA, Thomson AB, Meddings JB. Defining the role of fiberoptic sigmoidoscopy in the investigation of patients presenting with bright red rectal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1184-1187. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Mulcahy HE, Patel RS, Postic G, Eloubeidi MA, Vaughan JA, Wallace M, Barkun A, Jowell PS, Leung J, Libby E. Yield of colonoscopy in patients with nonacute rectal bleeding: a multicenter database study of 1766 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:328-333. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lewis JD, Shih CE, Blecker D. Endoscopy for hematochezia in patients under 50 years of age. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:2660-2665. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mehanna D, Platell C. Investigating chronic, bright red, rectal bleeding. ANZ J Surg. 2001;71:720-722. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Korkis AM, McDougall CJ. Rectal bleeding in patients less than 50 years of age. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:1520-1523. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Winawer SJ, Fletcher RH, Miller L, Godlee F, Stolar MH, Mulrow CD, Woolf SH, Glick SN, Ganiats TG, Bond JH. Colorectal cancer screening: clinical guidelines and rationale. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:594-642. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1353] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1225] [Article Influence: 45.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |