Copyright

©2009 The WJG Press and Baishideng.

World J Gastroenterol. Jan 14, 2009; 15(2): 144-150

Published online Jan 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.144

Published online Jan 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.144

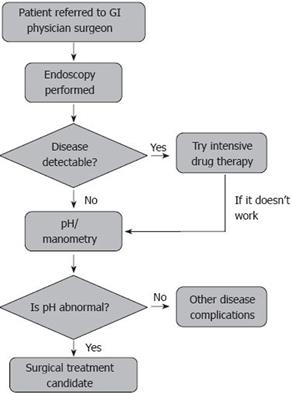

Figure 1 The pathway for a referred patient with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.

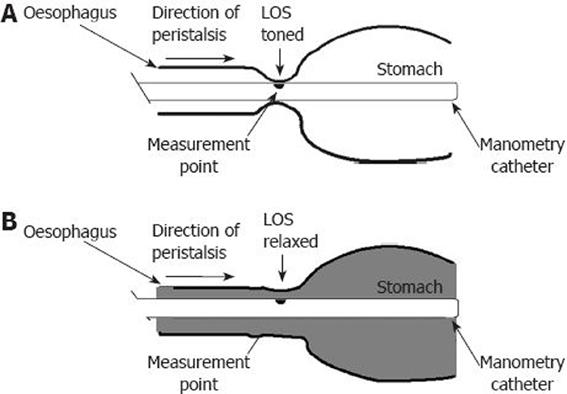

Figure 2 Simple manometry catheter shown in position in the LOS when it is toned.

A: Manometry catheter with the black dot on the catheter indicating the measurement point in the oesophago-gastric junction when a normal LOS is toned or competent causing the sensor to be engulfed or occluded by the sphincter; B: The pressure is indicative of the state of the chamber created by the lumen (area in grey) opening up between the oesophagus and stomach.

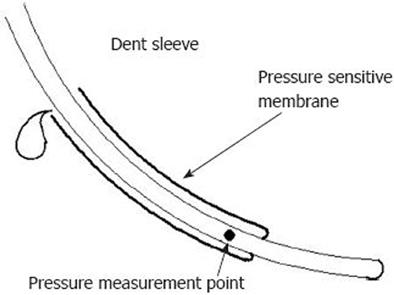

Figure 3 The dent sleeve.

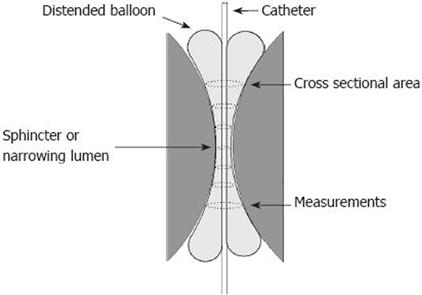

Figure 4 The functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) showing how a cylindrical shaped bag mounted on the distal end of a catheter can use impedance planimetry to measure multiple cross-sectional areas (CSAs) at fixed intervals along a catheter.

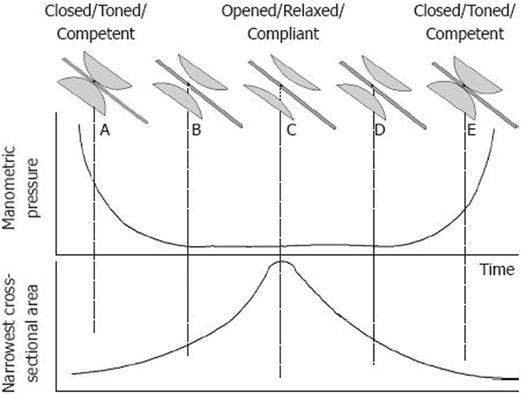

Figure 5 Diagram showing the difference between manometry and cross-sectional area (CSA) for measuring luminal changes in the oesophago-gastric junction during opening and closing.

At point A where the junction is closed, there is a high pressure and a low CSA representing the toned sphincteric region. As the sphincter relaxes, very quickly the manometry catheter is no longer squeezed, and at point B the pressure is zero or very low. However, this opening is detected by an increase in CSA at B. At C the sphincter is fully relaxed; but, there is still no useful information from manometry despite the CSA increasing even further. The pressure does not start to rise again until the sphincter is fully closed and toned at E.

- Citation: McMahon BP, Jobe BA, Pandolfino JE, Gregersen H. Do we really understand the role of the oesophagogastric junction in disease? World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(2): 144-150

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i2/144.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.144